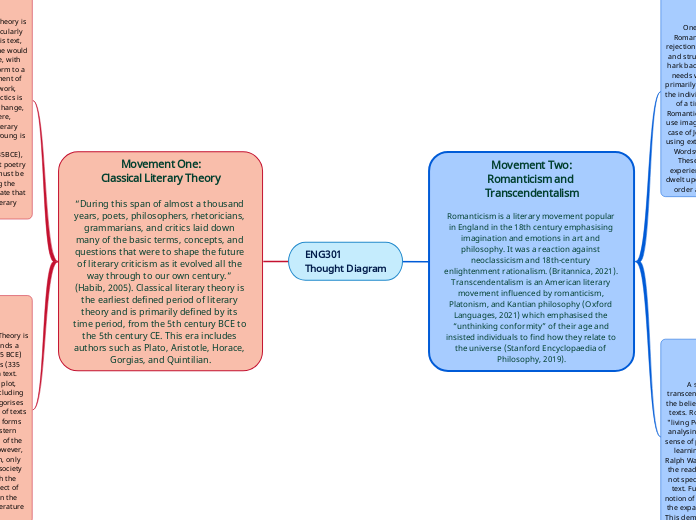

ENG301

Thought Diagram

Movement Two:

Romanticism and Transcendentalism

Romanticism is a literary movement popular in England in the 18th century emphasising imagination and emotions in art and philosophy. It was a reaction against neoclassicism and 18th-century enlightenment rationalism. (Britannica, 2021). Transcendentalism is an American literary movement influenced by romanticism, Platonism, and Kantian philosophy (Oxford Languages, 2021) which emphasised the “unthinking conformity” of their age and insisted individuals to find how they relate to the universe (Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, 2019).

Core Principle One:

Rejection of Modernity

One common theme that combines most Romanticist and Transcendentalist texts is the rejection of the modern need for order, rationality, and structure. Often, these writers would instead hark back to a time when they felt the individual's needs were put before the community's needs, primarily the Middle Ages. The emphasis placed on the individual, the love of nature, and reminiscence of a time past is evident in a large number of Romanticist writings. Often romanticist poems will use imagery linked to myths and legends, as is the case of John Keats' 'La Belle Dame Sans Merci', or using extensive nature imagery, such as in William Wordsworth's 'I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud'. These tropes and themes reject the modern experience of many of these poets where society dwelt upon the individual's duty to their society, to order and structure and rationality of thought.

Key Writer One:

Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge is a decorated romanticist poet writing the bulk of his works from 1795 to 1802. However, he is also a literary critic; he expresses this in Biographia Literaria (1817). Coleridge states that "I adopt with full faith the principle of Aristotle, that poetry is essentially ideal, that it avoids and excludes all accident" (Coleridge, 1817). This work provides some evidence in how Coleridge goes about his literary criticism; he is first and foremost looking at the construction of the text before he is examining the purpose of the text or texts as a whole. Furthermore, this style of literary criticism adheres to Coleridge's rejection of the modern social contract in preference of the individual. Coleridge acknowledges the individuality of the poet, recognising the "gifted individual". However, he then states that although it is the individual who writes the poem, poetry, in general, focuses upon "essential and universal features of a particular situation" (Mambrol, 2017), therefore emphasising the situation over the individual's influence on the poem. In a separate section of Biographia Literaria, Coleridge discusses the difference between primary and secondary imagination. Primary imagination is the "living Power and prime agent of all human perception", whereas secondary imagination is "an echo of the former... differing only in degree ad in the mode of its operation" (Coleridge, 1817). This understanding demonstrates the importance Coleridge places upon God in literary criticism, as his "primary imagination" stems mainly from the "living power", which is God. Hence, Coleridge approaches literature to uncover the beauty within by examining small details and overarching themes and concepts. This belief influences his literary criticism as he focuses on the societal influences on the poem but does not ignore the individual author or the "living Power" within.

Implications of Key Writer One:

Coleridge

Coleridge's literary criticism is indicative of the romanticist movement in which he writes. Coleridge rejects the modern manner of literary criticism favouring Aristotle's approach, linking to the romanticist tradition of favouring classical antiquity to modernity. However, he deviates from the emphasis on the individual evident in many romanticist writings as his literary criticism emphasises the need to understand the author's context to have a more complete understanding of the text and the creator. Hence, Coleridge emphasises a close reading of a text in the Aristotelian tradition while also stating that an understanding of context is needed to derive meaning.

Core Principle Two

God in Texts

A significant aspect of Romanticist and transcendentalist literary criticism centres around the belief that God can speak to humanity through texts. Romanticists such as Coleridge state that a "living Power" can inspire readers and creators in analysing and creating a text. This belief brings a sense of purpose to textual criticism as a method of learning from God about his creation. Further, Ralph Waldo Emerson puts significant emphasis on the reading of God through various texts, he does not specifically mention the Bible or any religious text. Further, transcendentalists believed in the notion of “Manifest Destiny” that God had ordained the expansion of the United States (Heidler, 2021). This demonstrates the importance of God in theory literary works and works of criticism.

Key Writer Two

Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson is "the most articulate exponent of American romanticism" (Mambrol, 2017). His work, both poetry and essays, places value upon individualism, intuition, the inherent goodness of human nature and the "unity of creation" (Mambrol, 2017). Similar to the work of Coleridge, Emerson emphasises the works of classical literature such as Plato, Shakespeare, and Chaucer. Further, Emerson also places high emphasis on the role of God in textual analysis, similarly to Coleridge. he states in his essay 'The American Scholar' (1837) that one should "read God directly", insinuating that one can "read God' in a variety of texts and is not limited to the Christian Bible. However, he disagrees with Coleridge's argument that to understand a text, one must understand the author's context, as Emerson states that audiences enjoy the works of exceptional poets due to the "abstraction of time from their verses". Hence, a reader can enjoy and understand poetry in his time without understanding the context of the original author and audience. This belief places more importance on the reader and author as individuals rather than on their societal context.

Further, Emerson suggests a hierarchy of texts, starting with any text on which one can "read God directly", followed by classical works such as Plato and Shakespeare. He suggests that works of history and science are valuable but must be learnt through "laborious reading" and that there are texts that a discerning reader will reject because they are "never so many times Plato's or Shakespeare's". Hence, Emerson's approaches literature with this hierarchy in mind. This hierarchy, in turn, affects how he undertakes literary criticism, examine the text largely outside of historical context, emphasising the individual author and reader.

Implications of Key Writer Two

Emerson

Emerson's work epitomises the Transcendentalist movement in the importance he places on God speaking through various texts, the importance of the creator as an individual, with modern enjoyment coming not from understanding context but from understanding the text outside of that context. This emphasis on the text outside of the context has implications for textual analysis as Emerson would analyse texts without, or with little reference to, the original context but rather focusing on how it creates joy for the modern audience.

Movement One:

Classical Literary Theory

“During this span of almost a thousand years, poets, philosophers, rhetoricians, grammarians, and critics laid down many of the basic terms, concepts, and questions that were to shape the future of literary criticism as it evolved all the way through to our own century.” (Habib, 2005). Classical literary theory is the earliest defined period of literary theory and is primarily defined by its time period, from the 5th century BCE to the 5th century CE. This era includes authors such as Plato, Aristotle, Horace, Gorgias, and Quintilian.

Core Principle One:

The Purpose of Texts

A critical core principle of classical literary theory is the purpose of texts. This principle is particularly evident in Plato's Republic. Throughout this text, Plato's character, Socrates, discusses how he would build a new republic in which all literature, with particular emphasis on poetry, would conform to a defined set of social norms for the betterment of society (Plato, 375 BCE). Similarly, in his work, Topics (350 BCE), Aristotle states that dialectics is helpful for "training, for conversational exchange, and sciences of a philosophical art." Here, dialectics is the discussion rather than literary criticism, but the purpose for training the young is the same.

However, in a separate treatise, Poetics (335BCE), Aristotle discusses the purpose of texts, but poetry in particular, is to imitate reality, not as it must be but as it could be. This debate regarding the purpose of texts is a core principle and debate that would continue through various other literary movements.

Key Writer One:

Plato

Plato (c. 429 - 347 BCE) is a critical thinker in philosophy. In Republic (375 BCE), his character Socrates is explicit on the power of text to shape a society's moral value. Socrates states that the contents of a text should represent the best of humanity so that children cannot know vice or ill but only wish to behave in a similar way to the heroes in the texts they read. Hence, the sole method of judging the value of a text is, according to Plato's character, Socrates, the moral value it provides society. However, it is difficult to know if this was Plato's view or if he was satirising the view of others. Since he writes as Socrates in dialogue, Plato never affirms ideas being presented (Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, 2017). Some scholars believe this method of writing to be a statement in and of itself; that Plato's texts are not supposed to represent one 'correct' idea but many ideas, not endorsed by the author, and simply logically presenting ideas for his audience to think about for themselves (Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, 2017; Hyland, 1968; Meinwald, 2020). However, despite this lack of direct endorsement of the ideas put forward in Republic, the central idea regarding the purpose of texts is prevalent throughout subsequent literary movements. This notion wholly guides Socrates' textual analysis. The moral guidelines of the society should bind every text and provide a platform from which to critique texts. Hence, Socrates' approach to literature defines his literary criticism process until they are one and the same.

Implications of Key Writer One:

Plato

Socrates’s that a text’s primary purpose is for the moral education of others, leads him to the necessary conclusion of banning books that teach lessons outside the moral confines of the society. Socrates discusses the need to censure Homer and other historical and poetic works, for their protagonists are flawed people. This idea is reflective of the classical movement as it focuses primarily upon the purpose of texts. For Plato, the purpose of texts is for the moral betterment of society. Hence, the implications of this are that all texts must fit the society's value system; there can be no exceptions to this rule for Socrates.

Core Principle Two:

The Construction of Texts

Another core principle of Classical Literary Theory is the construction of a text. While Plato spends a significant amount of time in Republic (375 BCE) discussing the purpose of a text, in Poetics (335 BCE), Aristotle discusses the creation of a text. Aristotle discusses literary ideas such as plot, characters, structure, and small details, including syllables, conjunctions, and verbs. He categorises genres and sub-genres and forms opinions of texts based upon these criteria. This discussion forms one of the earliest accounts of typical western literary criticism, including a deep reading of the text to decide upon value and meaning. However, Plato does not discuss textual construction, only that it should adhere to the morals of the society reading it. Hence, it is clear that although the construction of a text is an important aspect of classical literary theory, it is dependent on the critique's view regarding the purpose of literature as a whole.

Key Writer Two:

Aristotle

Aristotle (384-322 BCE) is considered one of the greatest philosophers, with only Plato being among his equals (Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, 2020). His primary work regarding literary criticism is Poetics (335 BCE) which focuses upon textual construction. For example, it defines key terms such as tragedy, although this is markedly different from a modern definition. It also discussed the purpose of poetry and producing a guide to elements of a close reading of a text. Aristotle's writing style differs significantly from that of Plato, choosing to use prose discourse rather than dialogue to communicate complex ideas. In this sense, it is easier to establish what Aristotle himself believed regarding textual criticism when compared to Plato's disavowal of any set beliefs in Republic (375 BCE). Aristotle discusses at length the notion that poetry is imitation and not an actual act of creation. However, this is not to diminish the poet's work, as he states that the function of poetry is to "relate not things that have happened, but things that may happen." (p95, Norton Anthology, 2nd edition). He goes on to state that the work of the poet in creating imitation is less historical as it is philosophical. This notion of poetry as imitation is a central tenant of how Aristotle approaches literature. The nuance of this idea also informs how he views textual analysis or criticism. By empowering the poet to be a philosophical creator of things that may be, Aristotle emphasises the small details in the text. Hence, Aristotle advocates for a close reading, considering small details including punctuation, connectives, syllables, and overarching elements such as characters, plot, and structure.

Implications of Key Writer Two:

Aristotle

Aristotle's belief that all poetry is an imitation, not of what has been but of what could be again links to the fundamental idea or debate regarding the purpose of texts. This belief is more nuanced than Plato's discussion on the purpose of texts, and as such, leads to a discussion regarding the second central tenant of classical literary theory; that of textual construction. This belief necessitates a close reading of a text in order to appreciate how it imitates and subverts reality using a mixture of content and form