Main topic

Main topic

Unfair Labour Practice:

Unfair Labour practice

Acting allowance

Dispute of interest

JA39/99

Hospersa

Benefit

The LAC in the HOSPERSA case, considered that a benefit, contemplated by a residual unfair labour practice was situated on the pole occupied by an antecedent right to a benefit. This right arises ex contractu, ex lege or through a collective agreement

JR1619/01

Eskom v Marshall & Others

Benefit

Legitimate expectation of provision of benefit

Noted that the LAC decision in HOSPERSA was binding but expressed the view that where an employee has a legitimate expectation to the provision of a benefit, although not a legal or contractual right, the failure to provide that benefit might amount to an unfair labour practice. Held that the benefit concerned must be an ascertainable advantage or privilege which has been created by the employer concerned; or one which the employer has declared it will consider conferring upon employees. Held that, for example, where an employee aspires to a promotion, he or she may have a legitimate expectation that if he or she meets the requirements of the post and beats the competitors, he or she will be promoted (at [20] - [23], referring inter alia to Administrator, Transvaal v Traub & Others 1989 (4) SA 731 (A) and Public Servants Association on behalf of Geustyn v Provincial Administration: Western Cape (2000) 21 ILJ 700 (CCMA)

JR1619/01

Eskom v Marshall & Others

Demotion

Employer reducing status of employee but leaving salary unchanged

the transfer from regional manager to branch manager constituted a demotion (at [15] - [19] and [24], referring to Taylor v Edgars Retail Trading (1992) 13 ILJ 1239 (IC) and Matheyse v Acting Provincial Commissioner, Correctional Services & others (2001) 22 ILJ 1653 (LC

JR1658/01

Van Wyk v Albany Bakeries Ltd & Others

Severance pay

that a dispute about the composition and amount of severance pay was a dispute of interest. Held further that the rate and formula were agreed,

D1676/02

Telkom (Pty) Ltd v CCMA; Cowling, MG & Cross, D

Demotion

demotion was when something to which the employee was entitled was withdrawn and that this could include status as well as a condition of employment

J1099/01

Minister of Justice & The Department of Justice v Bosch, D N.O.; Wepener, C & General Public Service Bargaining Council

Discrimination

when Ms Burger complained to her superior, a Ms van Zyl, about being placed close to black employees in the office. This was overheard by a fellow employee; at the disciplinary hearing she was found guilty and dismissed. She appealed and the sanction of dismissal was set aside on the basis that she had been issued a verbal warning, which had been confirmed in writing, as well as having apologised and had her apologies accepted by the aggrieved employees; held that the companys failure to protect him amounted to direct discrimination; Held that Old Mutual had discriminated against Mr Finca by failing to take the necessary steps to protect him against racism in the workplace and therefore were liable to pay him compensation.

C198/04

SATAWU obo Finca, X v Old Mutual Life Assurance Co (SA) Limited & Burger, J

Promotion

there were limited grounds on which an arbitrator, or a Court, could interfere with an employers discretionary powers, such as that of promotion.

C 172/04

Arries, L E v CCMA; Van Staden, P & Southern Sun Hotel Interests (Pty) Ltd & Others t/a Beacon Isle Timeshare Resort

Demotion

Compensation

criteria set out in the decision of the LAC in Ferodo (Pty) Ltd v De Ruiter (1993) 14 ILJ 1974, i.e. there must be evidence of actual financial loss; proof that the loss was caused by the unfair labour practice; the loss must be foreseeable; the award must endeavor to place the applicant in monetary terms in the position he would have been in, had the unfair labour practice not been committed; and the award must be fair and reasonable in the circumstances. The applicant must also take steps to limit his loss, e.g. take reasonable steps to find alternative employment.

JR987/05

Solidarity obo Kern v Mudau & Others

Promotion

No employment equity plan

Award difference remuneration had he been employed

JR593/07

City of Tshwane Metropolitan Council v SA Local Government Bargaining Council and Others

Promotion

Not ito Equity Plan

Exhaust provisions Chapter V EEA first

JS164/03

Minister of Safety and Security & Another v Govender

ULP

Commissioner should have joined successful candidate of own accord

JR2222/05

Minister of Safety & Security v De Vos & Others

Dispute one of interest

Upgrading of position and payment of acting allowance; re-evaluation of job; grading of post

JR 1843/05

Polokwane Local Municipality v South African Local Government Bargaining Council & Others

promotion

statutory regime regulating promotion

JR53/05

National Commissioner South African Police Service & Another v Cohen N.O. & Others

Suspension without pay

breach of the disciplinary code

disciplinary committee and the appeal committee were bound by the same limitations on the issue of the suspension without pay.

JR 197/08

UNISA v Solidarity obo Marshall & Others

Unfair suspension

Unfair suspension; right to be heard before suspension confirmed

J2632/09

Baloyi v Department of Communications & Others

Unfair suspension

Reasons for and supporting information regarding suspension to be provided opportunity to respond

J2632/09

Baloyi v Department of Communications & Others

Promotion

Not automatic right

Ee show arbitrariness or other unfairness

P54/09

South African Police Services v Safety and Security Sectoral Bargaining Council & Others

Benefit not = acting allowance

Other occasions granted

not demand for future payment

D644/09

Independent Municipal and Allied Trade Union obo Verster v Umhlathuze Municipality

Suspension

precautionary suspension cases the audi rule did apply.

all suspensions should be procedurally fair however required some qualification: fairness was a flexible concept that depended in each case

an opportunity to make written representations would ordinarily suffice.

JA58/10

MEC for Education, North West v Gradwell

Suspension

other case law cited

Chirwa v Transnet Ltd [2008] 2 BLLR 97 (CC).

the audi alteram partem rule applied was no longer authoritative since

JA58/10

MEC for Education, North West v Gradwell

right to fair labour practices in s 23 of the Constitution; was obliged to base her case on the applicable labour legislation that had been enacted under the Constitution

187(1)(d); was sufficiently persuasive not to prevent the applicant from pursuing her claim in those terms

C620/2011

De Klerk v Cape Union Mart International (Pty) Ltd

Suspension

Munisipal authority

C431/12

Nothnagel v Karoo Hoogland Municipality and Others

Demotion

C467/05

PSA & Other v Public Health & Welfare Sectoral Bargaining Council & Others

Demotion

Other case law cited

Sidumo judgment, the scope for reviewing commissioners awards had been highly limited. In essence, the function of the court would be to affirm commissioners decisions unless the evaluation of fairness by the commissioner was arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion or otherwise not in accordance with the established principles of law.

C467/05

PSA & Other v Public Health & Welfare Sectoral Bargaining Council & Others

Suspension without pay

only if so agreed

186(2)(b)

D813/06

SAPPI Forests (Pty) Ltd v CCMA & Others

ULP 7 years to refer, ongoing repeat itself every month

JA36/07

South African Broadcasting Corporation Ltd v CCMA & Others

Promotion

selection and appointment of an employee as akin to administrative decision-making, needed to be re-evaluated in the light of the constitutional recognition of the distinct labour rights to fair labour practices in s 23 of the Constitution and just administrative action in s 33.

C1148/2010

City of Cape Town v SAMWU and Others

Promotion

Not having a legitimate expectation. Failed to establish that any representation was made to him in clear, unambiguous terms devoid of any qualification. Failed to establish that the representation on which he relied was either competent or lawful for the decision maker to make

(JR1904/12) [2013] ZALCJHB 162

Mokoaledi v Minister of Health and Others

Performance bonus

Performance bonus not part of remuneration and dispute clearly an unfair labour practice dispute

Nature of dispute before court to be decided by court and not bound by a partys description of it

(JS 884/2011) [2013] ZALCJHB 266

Aucamp v SARS

Meaning of term benefit

A benefit for the purposes of s 186(2)(a) was not limited to an entitlement that arose out of a contract or by operation of law.

Apollo Tyres (Pty) Ltd v CCMA [2013] 5 BLLR 434 (LAC)

(JR 2209/13) [2014] ZALCCT 64

Thiso and Others v Moodley NO and Others

section 186(2)(b): any other unfair disciplinary action short of dismissal in respect of an employee

JR509/2014

Special Investigating Unit v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (JR509/2014) [2017] ZALCJHB 127 (21 April 2017)

[14]John Grogan: Employment Rights 1st ed (Juta & Co, Cape Town 2013) at 135-6.

To fall within the terms of section 186 (2) (b), disciplinary action against an employee short of a dismissal must be disciplinary both in nature and in intent. Action is disciplinary if it is aimed at correcting errant behaviour for which the employee is responsible. So, for example, a counselling session or a warning for incapacity does not fall within the scope of the definition. The definition is also concerned with disciplinaryaction. The decision to hold a disciplinary enquiry does not fall within the definition of an unfair labour practice- the action must have been instituted before an employee can refer a dispute relating to disciplinary action short of dismissal. The word action also suggests that employees may not refer a dispute over the content of an employers disciplinary policy. A dispute may be entertained only if the employer actually takes action. Only the Labour Court or, perhaps, the High Court, has the power to interdict a disciplinary hearing.

according to the Commissioner, had failed to comply with its own disciplinary code and procedure and therefore its actions were tantamount to an unfair labour practice by an employer on an employee. ... the Commissioner equally had no jurisdiction over the matter as there was no dispute between the parties.

demotion

JR2016/14

Sibanye Gold Limited v Solidarity obo Bezuidenhout and Others (JR2016/14) [2017] ZALCJHB 382 (12 October 2017)

unfair labour practice in relation to demotion and ordered the applicant to reinstate

The Policy was central to the first respondents case at arbitration and was documentary evidence before the Commissioner. The interpretation of the Policy was something the Commissioner was enjoined to apply his mind to. It was not reasonable for a decision-maker to accept Wagners understanding of one clause without applying his mind to the legal submissions before him, and the clause itself read in context.

Benefits

JR2498/13

Pretorius v G4S Secure Solutions (SA) (Pty) Ltd and Others (JR2498/13) [2015] ZALCJHB 414 (24 November 2015)

Apollo Tyres

transfer may in itself constitute a demotion

Dispute of right not excluded to ULP

JR2498/13

Pretorius v G4S Secure Solutions (SA) (Pty) Ltd and Others (JR2498/13) [2015] ZALCJHB 414 (24 November 2015)

MITUSA v Transnet Ltd (2002) 23 ILJ 2213 (LAC)

held that a dispute of right is not excluded from the ambit of an unfair labour practice.

Finding an accommodation and proving it to be reasonable is an onus resting on the employer. So is the onus of proving that a reasonable accommodation is unjustifiable. For her part, an employee with disabilities must prove that an accommodation that she proposes is reasonable on the face of it. She must also accept a reasonable accommodation and facilitate its implementation, even if it is a less than perfect or preferred solution.

Stocks Civil Engineering (Pty) Ltd v Rip NO & another [2002] 3 BLLR 189 (LAC)

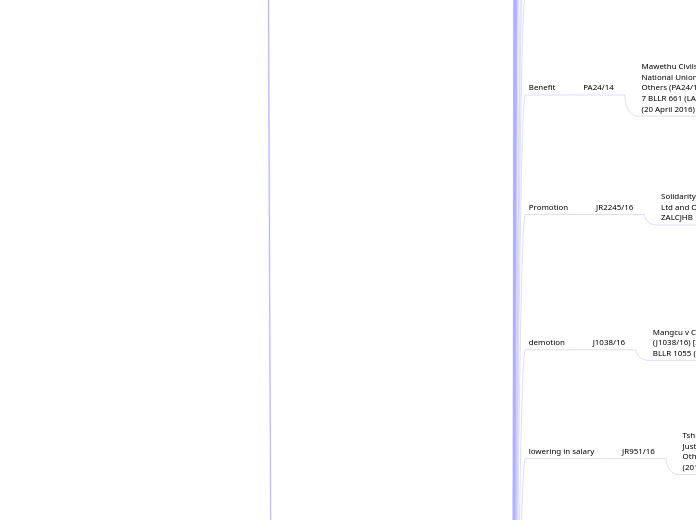

Benefit

PA24/14

Mawethu Civils (Pty) Ltd and Another v National Union of Mineworkers and Others (PA24/14) [2016] ZALAC 13; [2016] 7 BLLR 661 (LAC); (2016) 37 ILJ 1851 (LAC) (20 April 2016)

The practice of giving employees a full days paid leave in exchange for overtime for a lesser period in the preceding week undoubtedly falls within the concept of a benefit.

The dispute about payment for the leave day is indeed a dispute of right.

Promotion

JR2245/16

Solidarity obo Kriek v Sasol Synfuels (Pty) Ltd and Others (JR2245/16) [2016] ZALCJHB 190 (13 May 2016)

[5] It must also be mentioned that the arbitrators reliance on the principle that an employee may only raise an unfair labour practice dispute on the basis that they are claiming a right ex contractu or ex lege was misplaced in light of the LAC decision in Apollo Tyres SA (Pty) Ltd v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation & Arbitration & others(2013) 34 ILJ 1120 (LAC) , which confirmed the principle recognized in Gauteng Provinsiale Administrasie v Scheepers & others [2000] 7 BLLR 756 (LAC) that this was not a pre-requisite for establishing an unfair labour practice claim, albeit that those cases dealt with benefits :

The court [in Scheepers] clearly recognized that the unfair labour practice dispensation does create rights. This is a significant shift from the notion espoused in HOSPERSA that the right to a benefit must be derived from statute, contract or a collective agreement.

demotion

J1038/16

Mangcu v City of Johannesburg (J1038/16) [2017] ZALCJHB 351; [2017] 10 BLLR 1055 (LC) (22 February 2017)

Ndlela vSAStevedores Ltd(1992) 13 ILJ 663 (IC).

demotion is not a word which has some special meaning in labour law. It bears its ordinary meaning, namely to 'reduce to a lower rank or category'[5]. The converse of demotion is promotion. Demotion in the ordinary sense means a reduction or diminution of importance, responsibility, status and salary.

lowering in salary

JR951/16

Tshifhango and Another v Minister of Justice and Correctional Services and Others (JR951/16) [2017] ZALCJHB 97; (2017) 38 ILJ 2131 (LC) (23 March 2017)

30]In casuthe condition is the existence of an incorrect salary, salary level, salary scale being awarded to an employee. If the condition exists, the consequence is that the relevant executing authority shall be obliged to correct it. The executing authority exercises no discretion as the said consequence that flows from the existence of the condition arises by operation of law and not by the exercise of any discretion.

jurisdiction

JR634/1

Public Service Association of South Africa obo Members v MEC for Agricultural and Rural Development ( North West Province) (JR634/13) [2017] ZALCJHB 480 (12 October 2017)

unfair labour practice jurisdiction: performance management and development system and consequent payment of bonuses: constitutes a benefit under the unfair labour practice jurisdiction: dispute should be dealt with by bargaining council under normal dispute resolution processes under Chapter VIII of the LRA: review under Section 158(1)(h) not appropriate

[31] There is no doubt that as a general proposition, the Labour Court has the jurisdiction, in terms of Section 158(1)(h) of the LRA, to consider the applicants application to review and set aside the decision of the department relating to the payment of performance bonuses to employees, on the basis of the test as summarized above.

Gcaba v Minister for Safety and Security and Others (2010) 31 ILJ 296 (CC) at para 74

Merafong City Local Municipality v SA Municipal Workers Union and Another (2016) 37 ILJ 1857 (LAC) at para 36.

Section 158(1)(h) of the LRA refers to a jurisdictional power of the Labour Court. It specifically provides that the Labour Court 'may review any decision taken or any act performed by the State'. The only way the Labour Court is able to review is by hearing and determining an application for review of the acts and/or decisions contemplated in s 158(1)(h). That section should be read as not only conferring a power, but also jurisdiction upon the Labour Court.

32]But it is not as easy as that. The fact that the Labour Court has jurisdiction / power does not mean that the Court should exercise this power. In other words, and even thought the Court may have jurisdiction to consider such a review under Section 158(1)(h), it does not mean that it is appropriate for it to exercise such power, especially where there are other specifically prescribed means by way of which the issue can be resolved.

Hendricks v Overstrand Municipality and Another (2015) 36 ILJ 163 (LAC) at paras 10 12.

These dicta of the Constitutional Court support the general proposition that public sector employees aggrieved by dismissal or unfair labour practices (unfair conduct relating to promotion, demotion, training, the provision of benefits and disciplinary action short of dismissal) should ordinarily pursue the remedies available in ss 191 and 193 of the LRA, as mandated and circumscribed by s 23 of the Constitution.

Public Servants Association of SA on behalf of de Bruyn v Minister of Safety and Security and Another (2012) 33 ILJ 1822 (LAC) at para 32. See also the conclusion reached by the Court at para 34 of the judgment.

Therefore, the court a quo (although of the opinion that the application before it was in terms of s 158(1)(g) of the LRA) correctly proceeded to consider whether the LRA required the kind of dispute which existed between the appellant and the respondent to be resolved through arbitration. The court concluded that leave, including incapacity leave and temporary incapacity leave at the respondent's organization, is governed by the provisions of Resolution 5 of 2001 of the PSCBC, which is a binding collective bargaining agreement. This means that the dispute between the parties was required to be submitted to arbitration as it concerned the application and/or interpretation of the provisions of the PSCBC resolution

[43] It is useful to refer to some examples where such exceptional circumstances were found to exist. One of these is in fact the judgment in Minister of Labour[36] itself which dealt with the revocation of an employees designation of Registrar of Labour Relations in terms of the LRA,[37] and his resultant removal from that position, for reasons that were entirely irrational and invalid and where there in reality was no alternative remedy. A further example is Hlabangwane v MEC for Public Works, Roads and Transport, Mpumalanga Provincial Government and Others[38] which concerned a case where the right to discipline the employee had been specifically removed by statute (the Public Service Act) as a result of a transfer of the employee. A final example is by now the well known matter of Solidarity and Others v SA Broadcasting Corporation[39] which concerned the dismissal and victimization of reporters for being critical of policy decisions by the SABC as public broadcaster, which conduct violated the Constitutional duties of the employees, and even infringed on the right of the public to be properly informed.

47] How do the applicants then seek to avoid their dispute being considered to be one of an unfair labour practice? The answer is simple. It is all about labelling. The applicants initiated this dispute before this Court under Section 158|(1)(h) of the LRA, by way of, in my view, an act of deliberate labelling. The applicants in essence labelled the dispute as an infringement of their Constitutional right to legality, as evidenced by a number of causes of complaint specifically dealt with hereunder, and they specifically steer away from relying on unfairness. But, and as I have dealt with above, the Court should not be bamboozled by this kind of labelling.

[61]In summary therefore: The dispute of the applicants is quintessentially an unfair labour practice dispute, and as a matter of principle it should not be decided on the basis of a legality review in this Court

Promotion

CA07/2017

Public Servants Association obo Thorne v Department of Community Safety (Western Cape) and Others (CA07/2017) [2018] ZALAC 24; [2018] 12 BLLR 1173 (LAC) (8 June 2018)

Ncane v Lyster NO and Others(2017) 38 ILJ 907 (LAC) at para 25.

[16] When evaluating the suitability of a candidate for promotion an employer must act fairly. A promotion decision is however not a mechanical process and there is a justifiable element of subjectivity or discretion involved. Thus an arbitrator typically will interfere only where the decision is starkly unreasonable, improperly motivated or mala fide.[3] The employee bears the onus to prove the alleged unfairness.

Demotion

JR1493/16

Xoli v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (JR1493/16) [2018] ZALCJHB 156 (19 April 2018)

remunerated at a lower level

I do not see why such a complaint cannot be construed as a complaint about a demotion, whatever other implications it might have. Accordingly, I am satisfied that the arbitrator did indeed have jurisdiction to deal with the dispute

unfair conduct relating to benefits by unilaterally terminating a longstanding practice or right of granting employees special leave for the closure of the municipal offices during the festive season

J2769/2016

IMATU obo Members v City of Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality (J2769/2016) [2018] ZALCJHB 254 (3 May 2018)

reinstatement of special leave during festive season.

The ruling is quite simply that the City must reinstate the applicants members special leave days during the festive period. That ruling stands and the City has not taken it on review

Benefit

CA4/2018

National Union of Mineworkers obo Coetzee and Others v Eskom Holdings SOC Ltc and Others (CA4/2018) [2019] ZALAC 62; [2020] 2 BLLR 125 (LAC); (2020) 41 ILJ 391 (LAC) (4 October 2019)

A dispute about an unfair incorrect grading is thus an unfair labour practice dispute relating to the provision of benefits over which the CCMA will normally have jurisdiction.

not competent relief where the employee was dismissed

JR 917/16

Fidelity Security Service (Pty) Ltd v Socrawu obo Knoxwell Nengwekhulu and Others (JR 917/16) [2019] ZALCJHB 32 (25 February 2019)

Unfair labour practice. Reinstatement of suspended employee not competent relief where it turned out during arbitration that the employee was dismissed prior to commencement of arbitration proceedings. The award reviewed and set aside in so far as the relief of reinstatement awarded by the arbitrator.

policy relating to motor vehicle and fuel allowance constitutes benefit benefit regulated by terms of policy

JR 2160/15

Skhosana v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (JR 2160/15) [2019] ZALCJHB 39 (5 March 2019)

benefit: scarcity allowance

JR1148/2014

Maile v FOSKOR (Pty) Ltd (JR1148/2014) [2019] ZALCJHB 71 (2 April 2019)

[18] In this case, once it was accepted that the scarcity skills allowance was a benefit payable at the discretion of the employer, and that all the trainers except for Maile were paid such an allowance, the next enquiry was whether Foskor acted fairly[4] in exercising that discretion in depriving Maile of the allowance[5].

[41]...categorised as an unfair labour practice dispute in terms of section 186(2)(a) of the Labour Relations Act[1] (the LRA), being one allegedly involving unfair conduct relating to the provision of benefits to an employee in that should the job be upgraded, the employees will receive better benefits, being an advantage or privilege to which an employee is entitled as a right or granted in terms of a policy or practice subject to the employers discretion.[Thiso v Moodley NO [2015] 5 BLLR 543 (LC); and Apollo Tyres South Africa (Pty) Ltd v CCMA [2013] 5 BLLR (LAC) at para 50]

promotion : policy

JR369/1

Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality and Another v SALGBC and Others (JR369/15) [2019] ZALCJHB 91 (10 May 2019

[8] In these circumstances, Mr Pieterse submitted, the municipalitys failure to short-list him was grossly unfair. More significantly, the municipalitys decision to appoint the successful candidate further contravened its own policy in that it failed to adhere to the minimum requirements for the post.

2. The award granting Mr Pieterse protected promotion is reviewed and set aside, and substituted by an award that the applicant must re-do the appointment process from the shortlisting stage.

demotion

JR803/18

MTN (Pty) Ltd v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (JR803/18) [2019] ZALCJHB 152 (14 June 2019)

The second respondent found that the transfer of the third respondent amounted to a demotion despite the fact that he retained his title and his conditions of employment. The reason for this finding is that the transfer constituted a diminution in status, importance, prestige and responsibility of the applicant as the store in Rosebank was a lot smaller than the store in Morningside. (Although the second respondent did not refer to it, the reduction in the third respondents remuneration.) He also found that the transfer was not preceded by consultation.

Higher salary not benefit

JR 316/18

City of Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality v South African Local Government Bargaining Council and Others (JR 316/18) [2020] ZALCJHB 221 (15 May 2020)

[11] The head and tail of this dispute lies in the letter of 12 November 2010. It is apparent that Matee mistook this letter to be a contractual basis to pay Machete an increased salary. It is not. With reference to the Labour Appeal Court (LAC) judgment of Apollo Tyres SA v CCMA and others[[2013] 34 ILJ 1120 (LAC)], he mistook the claim of Machete to be one relating to benefits. A claim for a higher salary is not a claim relating to provision of benefits.

[12] Clearly, even if Apollo, supra may be applied, which in the Courts view is not applicable, the letter does not give rise to a contractual right nor a legitimate expectation.

respondents decision to cap the employers contribution to their post-retirement medical aid benefits (PRMA) was not in breach of contract or an unfair labour practice, unfair labour practice as contemplated in section 186(2)(a)

JA95/19

Skinner and Others v Nampak Products Limited and Others (JA95/19) [2020] ZALAC 43 (24 November 2020)

[16] In excess of 70% of the relevant employees accepted the offer at a cost of R236 million to Nampak. An offer in respect of the PRMA liability was also made to the retired employees, pensioners, who remained members of the scheme. About 75% of the pensioners accepted the offer at a cost of about R500 million to Nampak. The appellants did not accept the offer. They instead opted for the default option and sought to challenge the decision to cap the PRMA benefit.

[21] The appellants argued that a term purporting to afford Nampak a sole discretion to determine its own performance is void. They relied in this regard on NBS Boland Bank Ltd v One Berg River Drive CC and Others[3] to submit that no promise can be valid if it lies wholly within the choice of the promissor. A careful reading of the judgment discloses that it is not authority for the proposition advanced by the appellants...It is thus doubtful that courts should continue to follow the principle. The SCA considered it unnecessary to decide the point because the rule does not apply to a contractual power to fix a prestation other than a price or rental. It held there was no reason to extend the common law rule to other types of contractual discretions.

[23] Hence, generally, a stipulation conferring upon a contractual party the right to determine a prestation is unobjectionable. There is accordingly no basis to hold clause 4.1 of the policy invalid and the Labour Court did not err in making that finding. This does not mean, as the Labour Court correctly understood, that an exercise of such a contractual discretion is necessarily unassailable. In terms of our common law, unless a contractual discretionary power was clearly intended to be completely unfettered, an exercise of a contractual discretion to alter a prestation must be made arbitrio bono viri (reasonably).[Dharumpal Transport (Pty) Ltd v Dharumpal 1956 (1) SA 700 (A) 707 A-B; Moe Bros v White 1925 AD 71,77; Holmes v Goodall and Williams Ltd 1936 CPD 35,40; Belville-Inry (Edms) Bpk v Continental China (Pty) Ltd 1976 (3) SA 583 (C) 591 G-H; and Remini v Basson 1993 (3) SA 204 (N) 210 I-J] The essential question in this case, therefore, is whether Nampak exercised its discretion under clause 4.1 of the policy reasonably.

[25]...Clause 4.1 of the policy reflects a clear intention to permit adjustment (on legitimate or reasonable grounds) of the PRMA benefit of employees still in employment prior to their retirement.

[26] The requirement that a contractual discretion should be exercised reasonably, arbitrio bono viri, means that the relevant party must not act in bad faith, arbitrarily or capriciously and should endeavour proportionally to balance the adverse and beneficial effects of the proposed decision or action. A court reviewing the justifiability of such an exercise of discretion should permit the holder of discretion a margin of appreciation in balancing the relevant interests and considerations and avoid substituting the discretion with its own merely because it might have exercised it differently.

[40]...The contractual entitlement of the appellants is restricted by clause 4.1 of the policy which permitted Nampak at its discretion to alter the entitlement prior to its vesting on retirement. The claim of the appellants, in the light of clause 4.1 of the policy, is essentially a claim for an entitlement they did not have as future pensioners. Accepting that they have no entitlement under clauses 3.3.3 and 3.3.5 of the policy, their dispute amounts to a claim for new rights and is thus akin to a dispute of interest, in the final analysis a matter for collective bargaining. [41] There can only be a breach of contract or unfair labour practice if Nampak is shown to have exercised its discretion in terms of clause 4.1 of the policy unreasonably or unfairly.

[42] The issue of affordability is not decisive. When assessing whether the employer has acted reasonably or fairly in exercising its discretion to alter its prestation, its operational requirements are undoubtedly a relevant consideration. An intention to increase profitability is an entirely legitimate commercial rationale. The unfair labour practice jurisdiction is not meant to restrict the proper pursuit of profit by the employer. The point was made by Zondo JP (as he then was) in Frys Metals (Pty) Ltd v National Union Metal Workers of SA & others[(2003) 2 ILJ 140 (LAC) at para 33] when he said in relation to the commercial rationale for operational requirements dismissals:[A]ll the Act refers to, and recognises, in this regard is an employers right to dismiss for a reason based on operational requirements without making any distinction between operational requirements in the context of a business the survival of which is under threat and a business which is making profit and wants to make more profit.[See also General Food Industries v Food and Allied Workers Union (2004) ILJ 1260 (LAC) para 52...[43] These are matters falling within executive and managerial prerogative.]...[44] There is no evidence of any illegitimate or ulterior motive or caprice. The process was transparent and sought fairly to balance proportionally the competing interests at stake.

Section 188A of the LRA inquiry constitutes disciplinary action short of a dismissal

JR 2236/17

Laubscher v General Public Service Sectoral Bargaining Council (GPSSBC) and Others (JR 2236/17) [2020] ZALCJHB 103; [2020] 10 BLLR 1053 (LC) (15 June 2020)

[40] The dispute referred by the Applicant was not disciplinary sanction short of dismissal but rather disciplinary action short of dismissal. This disciplinary action short of a dismissal constitutes an unfair labour practice and may be only brought by an employee against an employer as it arises out of an employment or a "live relationship". The elements will be unfairness, arising from a disciplinary action, which action must have commenced; and such a disciplinary action must have the end results of falling short of a dismissal; example of it being withdrawn. Every employee enjoys a constitutional right to fair labour practice and our courts need to define and/or expand on these rights as provided for in the LRA.

Benefit: commission

JR 1356/18

Oracle Corporation South Africa (Pty) Ltd v Malgas and Others (JR 1356/18) [2020] ZALCJHB 136 (17 August 2020)

[45] The fact that the negotiations between the South African team and Multichoice in South Africa collapsed when Naspers opted for a global contract with Myriad ought to have been the end of the matter, as Malagas efforts did not bear any fruit. Thus, in the absence of evidence to point to the influence of Malagas or the applicants efforts being utilised to seal the deal, which evidence was not placed before the Commissioner, it follows that her conclusions that Malagas played a role in the deal are indeed not supported by any evidence, and are at best speculative. Thus, reliance by the Commissioner on unsupported evidence, speculation, and/or evidence insufficiently reasonable to justify a conclusion rendered her award reviewable[9].

[46] Once it was concluded that Malagas played no role in the ultimate deal, that ought to have been the end of the matter. The Commissioner nonetheless proceeded to find that commission was payable albeit subject to the discretion of the applicant, and that the applicant did not exercise its discretion fairly. This finding is equally without a basis in the absence of conclusions that Malagas played a role or the in the absence of the teaming agreement. The applicant cannot be accused of having applied its discretion unfairly, or acted arbitrarily, capriciously or inconsistently in not paying commission, in circumstances where the basis for such payment was not demonstrated.

[52] I therefore agree with the submissions made on behalf of the applicant that a finding of unfair labour practice on the part of the applicant cannot be one that a reasonable commissioner could have come to in the light of the material that was served before her.

Benefit: PRMB

JA03/2020

Total SA (Pty) Ltd v Meyer and Others (JA03/2020) [2021] ZALAC 12 (2 June 2021)

[25] Turning to the first respondents cause of action, it was predicated on the definition of unfair labour practice as set out in s 186 (2) (a) of the LRA, which includes any unfair act or omission that arises between an employer and an employee involving unfair conduct by the employer relating to the provisions of benefits to an employee. In Apollo Tyres South Africa (Pty) Ltd v CCMA [2013] 5 BLLR 434 (LAC) this Court gave content to the phrase the provisions of benefits to an employee as follows:In my view, the better approach would be to interpret the term benefit to include a right or entitlement to which the employee is entitled (ex contractu or ex lege including rights judicially created) as well as an advantage or privilege which has been offered or granted to an employee in terms of a policy or practice subject to the employers discretion. (my emphasis)

[33]...This it failed to do, in that there was no evidence put up to gainsay the first respondents case of differentiated treatment. The only conclusion that can be drawn is that reached by the court a quo, namely, that the appellants decision was arbitrary, capricious and inconsistent, and thus amounted to an unfair labour practice in terms of s 186 (2) (a) of the LRA.

Benefit: Definition and (1.1) The applicant succeeded to prove that the first respondent committed an unfair labour practice relating to non-payment of its members acting allowance

JR 932/19

Independent Municipal and Allied Trade Union obo Dhlamini v Moqhaka Municipality and Others (JR 932/19) [2021] ZALCJHB 60 (24 May 2021)

[12] Regarding the first issue, the arbitrator relied on the Concise Dictionary, the judgments in Schoeman and another v Samsung Electronics SA (Pty) Ltd; Sithole v Nogwaza NO and others and Northern Cape Provincial Administration v Hambridge NO and others in reaching the following conclusion:27. Although opinions as to what constitutes a benefit (as opposed to remuneration) differ, the common thread running through all the positions and academic writings is that a benefit constitutes a material benefit such as pensions medical aid, housing subsidies, insurance, social security or membership of a club or society. 28. In other words, the benefit must have some monetary value for the recipient and be a cost to the employer. It is also something which arises out of a contract of employment.

29. According to Northern Cape Provincial Administration v Hambridge NO [1999] 7 BLLR 698 (LC) benefit is a supplementary advantage conferred on an employee for which no work is required. About the letter in hand, the acting position is not available to all employees. 30. The difference is that benefits are available to all employees, but an acting position is only available to employees that qualify or meet the minimum requirements and who are to undertake extra work.

[13] It is apparent from the reading of the award that the arbitrator did not consider the later developments in law, particularly in relation to the notion that an employee has to prove a pre-existing right prior to bringing a benefit claim. In Independent Municipal and Allied Workers Union obo Vester v Umhlahhuze Municipality,[2] this Court dealt with a review of an award in terms of which an arbitrator had found that an acting allowance did not constitute a benefit in term of section 186(2)(a). Having reviewed the case law and the academic writings, the Court found, inter alia, that: an unfair labour practice dispute over an acting allowance, in which an employee is making the claim on the basis that it was granted to him or others in similar circumstances on other occasions, is a claim that the employer has unfairly refused to confer the benefit on the occasion in question

Something extra

JR2267/15

Office of the Premier: Limpopo Provincial Government v Phooko NO and Others (JR2267/15) [2021] ZALCJHB 106 (26 May 2021)

[11]...Regard being had to the decision of Apollo Tyres South Africa (Pty) Ltd v CCMA[2] a benefit must be something extra[3] that arises from a contract, a party claiming a benefit out of a contract must prove the existence of that contract and the term that gives him or her that right to the benefit. This Court accepts that it is possible that during the benefits dispute parties may quibble around the terms of that contract, which may lead an arbitrator into a situation where the terms of the contract are interpreted using the known and accepted interpretative tools to find or not find the right.

[13] It has long been held that a benefit is something extra other than remuneration which is contractually, legislatively guaranteed or legitimately expected. The Resolution does not guarantee any benefit but a translation promotion or a pay progression salary increment. The salary increment is not something extra but remuneration. This Court takes a firm view that Mokubela has nonetheless failed to show that a benefit is due to her contractually. That being the case, a conclusion that the Office of the Premier has committed an unfair labour practice in relation to the provision of benefits is not one a reasonable decision maker may reach.

[14] Assuming that benefits are involved in this dispute, the question that must follow is whether Mokubela had discharged the onus that the Office of the Premier has committed an unfair labour practice. An unfair labour practice claim is akin to a contractual claim. The employee must prove (a) that a contract is extant, if reliance is placed on one, and that the other party has breached that contract.

Demotion: transferred back to her previous post with the concomitant reduction of salary

CA17/2020

Department of Defence v Farre and Others (CA17/2020) [2021] ZALAC 33 (11 October 2021)

she was then transferred back to her previous post with the concomitant reduction of salary and obligation to repay R 178 88.98 clearly constituted the kind of practice which falls within the scope of principle of an unfair labour practice

Apollo Tyre South Africa (Pty) (Ltd) v CCMA [2013] 5 BLLR 434 (LAC) this Court agreed with the minority judgment of Goldstein AJA in Department of Justice v CCMA (2004) 25 ILJ 248 (LAC) para 14

[19] Whatever the position it seems to me respectively with the view expressed in paragraph 9 that item 2(1)(b) provided only for rights which arose ex contractu ex lege was clearly wrong. If that was so, the provision would have been redundant since such rights would have been enforceable in the absence of item 2 (1)(b). It is significant that item 3 (4)(b) expressly provided for a dispute referred to inter alia in item 2 (1) (b) to be resolved in arbitration. It is significant to that the introductory words in item 2 (1) and the cardinal words in item 2 (1)(b) concerned an unfair labour practice and unfair conduct. Just as the LRA provides for disputes arising from unfair dismissals in respect of which there are no contractual remedies and remedies of common law to resolve an arbitration so was item 2 (1)(b) designed for situations when neither the contract of employment nor the common law provided an employee with a remedy.[20] In following this approach, Musi AJA in Apollo Tyres said at para 51:An employee wants to use the unfair labour practice jurisdiction in s 186 (2) (a) relating to promotional training does not have to show that he or she has a right to promotion or training and ought to have remedy when the fairness of the employers conduct relating to such promotion (or non-promotion) or training is challenged.

[21] In my view, therefore the third respondent was correct to hold that the conduct of the appellant was unfair in that it was unfairness of the practice rather than the breach of a preexisting right which formed the basis of the claim.

[14]... The court a quo thus held that the third respondent had reasonably concluded that this action on the part of the appellant constituted a demotion. The learned judge also found that the third respondent had correctly found that the appellant had not complied with the audi alteram partem rule before it had taken the decision effectively to demote the first respondent. Further the learned judge found that the reason for this demotion was that the employer dragged its feet in reclassifying her post. Furthermore, the functions which the first respondent had performed would have always been scientific and not administrative which was clearly evident from the description of that which she was required to perform in terms of her post.

continuous

JR 678/16

Harmony Gold Mining Company Limited-Kalgold Operations v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (JR 678/16) [2022] ZALCJHB 25 (18 January 2022)

20] Similarly, the ground that the commissioner committed an error of law in finding that the unfair labour practice was continuous is without any merit. In CCMA v CCMA[(2010) 31 ILJ 592 (LAC)], the LAC stated as follows:While an unfair labour practice/unfair discrimination may consist of a single act it may also be continuous, continuing or repetitive. For example where an employer selects an employee on the basis of race to be awarded a once off bonus this could possibly constitute a single act of unfair labour practice or unfair discrimination because like a dismissal the unfair labour practice commences and ends at a given time. But, where an employer decides to pay its employees who are similarly qualified with similar experience performing similar duties different wages based on race or any other arbitrary grounds then notwithstanding the fact that the employer implemented the differential on a particular date, the discrimination is continual and repetitive. The discrimination in the latter case has no end and is therefore ongoing and will only terminate when the employer stops implementing the different wages. Each time the employer pays one of its employees more than the other he is evincing continued discrimination.

[17] The applicant further submitted that to an extent that NUM became aware of the applicants omission to include them in the 50/50 medical aid benefits scheme in March 2015, it should have referred the dispute in June 2015. Further that as the dispute was referred on 2 October 2015, it was referred more than 90 days late, which is excessive.

[11]...respondents were taken over by the applicant in 2002 in terms of section 197, their employment contracts required the applicant to contribute 100% towards their medical aid contributions. However, this was not done by the applicant. Instead, the applicant deducted 100% medical aid contribution from their salaries, even though it contributed 50% for its other employees.

[22] These concerns implicate the procedural fairness of her hearing and it is well established that the benchmark in matters where some form of procedural unfairness is alleged remains Avril Elizabeth Home for the Mentally Handicapped v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration[(2006) 27 ILJ 1644 (LC) 1651C-1652A], where the court stated that it will ordinarily hold an employer to no more than the statutory code of good practice or, if they are more favourable, the terms of the employers disciplinary code and procedure. The test to be applied is not that which applies in a criminal trial.

acting alowance

JR1450/17

Department of Military Veterans v Moche and Others (JR1450/17) [2022] ZALCJHB 44 (7 March 2022)

[9] Although the commissioner dismissed the first respondents claim to be upgraded to level 10, he ordered the applicant to pay the first respondent the difference in salary between the level 6 and level 10 positions.

2. The matter is remitted to the second respondent for a hearing de novo before a commissioner other than the third respondent.

[16] Section 186 (2) (c) of the LRA provides that it is an unfair labour practice to fail or refuse to re-instate or re-employ a former employee in terms of any agreement.

JR 1534/20

Moloko v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (JR 1534/20) [2022] ZALCJHB 76 (9 March 2022)

[16]...Other than the unfair act or omission that must arise between an employer and an employee, the essential elements for a claim under the section are; (a) failure or refusal; (b) to re-instate or re-employ a former employee; and (c) in terms of an agreement. Therefore, the right to be reinstated or reemployed must arise from an agreement. John Grogan in his work Workplace Law[2] opines that Section186 (2) (c) differs from selective dismissal in that affected employees need not prove that they were treated selectively mere breach of an agreement is sufficient. He further opines that employees alleging this form of unfair labour practice must prove the existence of an agreement that imposes an obligation on the employer to re-employ them. I plentifully agree. A claim for an unfair labour practice in relation to the failure or refusal to reinstate or re-employ is akin to a breach of contract claim. Like in any contractual claim, the former employee as a party must establish the existence of an enforceable agreement. Absent such an agreement, a former employee does not have a claim for an unfair labour practice.

[14] With regard to an unfair labour practice, the legislature makes reference to (a) an existence of a dispute; (b) about an unfair labour practice; (c) and an employee alleging an unfair labour practice. As defined, a dispute includes an alleged dispute. Thus, what entitles an employee to enter the dispute resolution zone in relation to an unfair labour practice is an allegation as opposed to showing that an employee is dismissed in a dismissal situation. Section 191 (5) (b) (iv) of the LRA is explicit, the council or the Commission is obligated to arbitrate at the request of an employee if the dispute, which includes an alleged dispute, concerns an unfair labour practice. In other words the licence to arbitration is the existence of a dispute or an alleged dispute concerning; related to or about an unfair labour practice. Therefore, it cannot be said that Zwane lacked jurisdiction in an objective sense to arbitrate an allegation that Ashanti failed or refused to reinstate or re-employ Moloko as a former employee in terms of any agreement. The issue whether there was an agreement goes to the merits as opposed to jurisdiction. Concluding that non-existence of an agreement to reinstate or re-employ is a jurisdictional issue is an error, which is not material enough to affect a reasonable outcome of failure by Moloko to discharge an onus to show an unfair labour practice within the meaning of section 186 (2) (c) of the LRA.

promotion

J1943/2019

MEC for Gauteng Department of Infrastructure Development v Ramapepe (J1943/2019) [2022] ZALCJHB 98 (12 May 2022)

[98] Rationality was defined by [C. Hoexter Administrative Law in South Africa, 2nd ed, Juta, 2012, at p 340.] as follows:[t]his means in essence that a decision must be supported by the evidence and information before the administrator as well as the reasons given for it. It must also be objectively capable of furthering the purpose for which the power was given and for which the decision was purportedly taken.

[99] The Applicants case is that the Respondents appointment to the post of Deputy Director: Professional Secretariat Services is irrational and cannot survive rationality scrutiny, considering the absence of a proper relationship between the action of the functionary and the facts and information available to her and on which she purported to base the decision.[100] In my view, there is merit in the Applicants submissions. The purpose of the recruitment and selection process prescribed under the PSA and PSR is to ensure equality and fairness in the filling of posts in the public service. It is for these reasons that the PSA prescribes that the evaluation of candidates should be based on inter alia training, skills, competence, knowledge and the need to redress the imbalances of the past. The PSR provides that the selection committee shall make a recommendation on the suitability of a candidate after considering only, inter alia, information based on valid methods, criteria or instructions for selection that are free from any bias or discrimination and the training, skills, competence and knowledge necessary to meet the inherent requirements of the post.[101] In Khumalo, it was held that it is neither fair nor in compliance with the dictates of transparency and accountability for the State to mislead applicants and the public about the criteria it intends to use to fill a post. The formulation and application of requirements for a particular post is a minimum prerequisite for ensuring the objectivity of the appointment process.[Khumalo v Member of the Executive Council for Education: Kwazulu-Natal[2014 (5) SA-579 (CC).] (Khumalo)]

demotion in terms of section 186(2)(a) of the LRA.

JR1746/19

Capitec Bank Ltd v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (JR1746/19) [2022] ZALCJHB 166 (22 June 2022)

[34] It is clear from the evidentiary analysis at paragraphs 35, 36 and 40 of the Award that the Commissioner reasoned that the status of Ms Mahlangus previous Key Accounts Manager position was greater than that of her new Regional Manager position.[35] The Commissioner reached this conclusion despite evidence that the Key Accounts Manager position had no reports, slightly lower remuneration and was on the same occupational level (Lower D Level) as the Regional Manager position. In doing so, the Commissioner considered that Ms Mahlangus concern was not with her remuneration or occupational level, but rather with her alleged reduction in status in the organisation.

[39] However, for the above reasons, I do not find fault with the Commissioners reasoning that Ms Mahlangus status in the organisation was reduced when she was moved from the position of Key Accounts Manager for the public service to Regional Manager for Mpumalanga. As for the significance of that finding, in Van Wyk v Albany Bakeries Ltd and others[AA1] [[2003] 12 BLLR 1274 (LC) at para 17.], the Labour Court stated that:A demotion has therefore less to do with the demoted employees salary. It would seem the reduction of salary is only a secondary factor, the primary and decisive factor being the reduction in rank, position or status of the employee concerned.[40] Similarly, in Taylor v Edgars Retail Trading[(1992) 13 ILJ 1239 (IC)] the Industrial Court referred to the concept of demotion, as formulated by Scoble[See: C. Norman-Scoble Law of Master and Servant in South Africa (Butterworth and Co (Africa), 1956).] as follows:Where a servant is employed to perform a particular class of work and contracts to perform work of a particular character, is thereafter instructed to perform work of a more menial nature, he may be said to have been degraded in his status, and as such action by his employer may in certain circumstances be regarded as tantamount to dismissal.[][41] The above dictum was cited with approval in Matheyse v Acting Provincial Commissioner, Correctional Services and others[(2001) 22 ILJ 1653 (LC) at para 27.]. In Matheyse (supra) the Labour Court further elaborated on the issue of demotion and stated:In a series of decisions (which predated the LRA) the civil courts have gone further and applied a wider definition to the concept of demotion in the labour relations context, holding that it applies even where employees retain their salaries, attendant benefits, and rank, but have suffered a reduction or diminution in their dignity, importance and responsibility or in their power or status.

Capitec Bank Limited is ordered to pay compensation to Ms Mahlangu equal to three months remuneration calculated according to the total cost-to-company monthly remuneration received by Ms Mahlangu in the position of Key Accounts Manager.

Benefit: Travelling allowance

JR 1724/2020

Polokwane Municipality v South African Local Government Bargaining Council and Others (JR 1724/2020) [2022] ZALCJHB 197 (29 July 2022)

[6] In the present instance, the subject of a travelling allowance is not the subject of any contractual term. Both municipalities regulate the payment of the allowance in terms of a policy. The difference in the policies, as I have indicated, is that the Aganang policy permits payment of a travel allowance for business travel both inside and outside of the municipal boundary; in the case of the applicant, payment is limited to travel outside municipal boundaries.

[5] In general terms, a benefit must arise ex contractu or ex lege. The courts have always defined benefit narrowly, so as to avoid the consequence of a limitation on the right to strike in support of improved conditions of employment. In Protekon (Pty) Ltd v CCMA & others [2005] 7 BLLR 703 (LC), this court observed that in terms of many employee benefit schemes, employers enjoy a range of discretionary powers in terms of their policies and rules, and held that the primary purpose of the unfair labour practice protection in relation to employee benefits was to permit scrutiny of employer discretion. That conclusion was upheld in Apollo Tyres South Africa (Pty) Ltd v Commission for Conciliation Mediation and Arbitration [2013] 5 BLLR 434 (LAC), where the Labour Appeal Court held that a benefit could arise from a contract of employment, or a policy or practice some advantage or privilege arising from a policy or practice where the employer is afforded a discretion in relation to the subject of that policy or procedure (at paragraph 50). What unfairness in this context requires is some failure to meet an objective standard and may be taken to include arbitrary, capricious or inconsistent conduct (at paragraph 52).

[7] I am not persuaded that the provisions of the respective policies on travelling allowances constitute a benefit for the purposes of section 186 (2)(a) of the LRA. The policies provide for the reimbursement of costs incurred while travelling on the employers behalf, rather than a benefit. Further, there is no exercise of any discretion by the employer in this instance the terms of the policy are fixed and apply to all employees covered by it.

Suspension: 182(2)(b) of the LRA, alleging that the Applicant had not furnished him with enough detail and reasons for his suspension

JR1254/16

Wholesale & Retail Sector Education and Training Authority (W&RSETA) v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (JR1254/16) [2022] ZALCJHB 209 (4 August 2022)

[16] The answer to the first supplementary question depends on the legal standard applicable to the particularity of suspension notices. It is trite that the law imposes a duty of fair dealing on employers whenever they make decisions affecting their employees, and that when contemplating suspensions, this duty obliges employers to, at a minimum, have a justifiable prima facie reason to believe that the employee has engaged in serious misconduct; has an objectively justifiable reason to deny the employee access to the workplace; and afford the employee an opportunity to state a case before the employer makes a final decision on the suspension.[Mogothle v Premier of the North West Province and Another [2009] 4 BLLR 331 (LC) at para 39.]

[18] The Applicant referred this Court to Mere v Tswaing Local Municipality and Another,[(2015) 36 ILJ 3094 (LC) (7 July 2015)] where this Court, per Snyman AJ, held that an employee who had been furnished with an admittedly unspecific notice of intention to suspend but had been invited to a meeting where the reasons for his suspension were verbally explained, was lawfully suspended. This case, however, differs from the present, in that it dealt not with an unfair labour practice but concerned itself with whether the suspension was lawful in terms of the Local Government: Disciplinary Regulations for Senior Managers. Although the case itself does not assist much, it does raise the question whether, in suspension proceedings, the employee must be furnished with all specific reasons in writing, or whether it is sufficient for the employee to simply be made aware of the reasons thereof, verbally or otherwise.

[19] In Sol Plaatje Municipality v SA Local Government Bargaining Council and others[(2022) 43 ILJ 145 (LAC).] the Labour Appeal Court cautioned courts and tribunals against an unduly strict and technical approach to the framing and consideration of disciplinary charge sheets and postured that a disciplinary charge may be broad, as long as a reasonable inference may be drawn that the accused's conduct fell within that scope.[20] Although Sol Plaatjie was in the context of actual disciplinary proceedings, it is worth noting that the standard in precautionary suspensions is lower than in disciplinary proceedings. It bears repeating that "[w]here the suspension is precautionary and not punitive, there is no requirement to afford the employee an opportunity to make representations."[Long v South African Breweries (Pty) Ltd and Others; Long v South African Breweries (Pty) Ltd and Others [2019] 6 BLLR 515 (CC) at para 24.] Where no legal requirement for a hearing exists, it cannot be that nothing but written reasons for the contemplated suspension shall suffice.

[22] The legal standard in precautionary suspensions, as we have seen, is not strict specificity in writing; it is sufficient for an employee to be informed (whether in writing or verbally) of the reasons for his or her suspension.

Disciplinary action short of dismissal

J 2024/19

Maloisane v Judge President of the Labour Court and Others (J 2024/19) [2022] ZALCJHB 219 (11 August 2022)

[85] From the record, the facts establish that the Applicant was subjected to a disciplinary hearing on the following allegations _(1) threatening supervisor and foreman that you will go to HR because you dont agree with the company rules, (2) threatening supervisor and informing him that you already went to your union instead of following the correct procedure.[86] The disciplinary process resulted in the issue of a final written warning on 12 April 2019.[87] Subsequent to the filing an unfair labour practice dispute with the CCMA, the union was informed in writing on 17 May 2019 that the final written warning had been cancelled.[88] The commissioner was called upon to determine whether the alleged unfair labour practice had been committed and if so, he was required to determine the appropriate relief.[89] The fact that the final written warning had been cancelled does not detract from the fact that Applicant was subjected to a disciplinary process which resulted in the issue of a final written warning. The commissioner was required to look into this process and make a determination on whether it was fair or not.[90] Accordingly, the commissioner`s ruling that the CCMA does not have jurisdiction is reviewed and set aside.

Promotion

JR 590/20

Nomtshongwana v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (JR 590/20) [2022] ZALCJHB 254 (12 September 2022)

[16] In Ncane v R Lyster NO,[[2017] 4 BLLR 350 (LAC) at paras 25 and 26.] the court outlined an approach to be taken by the commissioner when arbitrating disputes concerning unfair labour practice as defined in section 186(2)(a) and stated as follows:[25] When it comes to evaluating the suitability of a candidate for promotion, good labour relations expect an employer to act fairly but it also acknowledges that this is not a mechanical process and that there is a justifiable element of subjectivity or discretion involved. It is for this reason that the discretion of an arbitrator to interfere with an employers substantive decision to promote a certain person is limited and an arbitrator may only interfere where the decision is irrational, grossly unreasonable or mala fides. See on this Goliath v Medscheme (supra).[26] But where an employer provides that certain rules apply as regards the decision to promote or to recommend a candidate for promotion, e.g. as in this case, the candidate who scores the most points must be recommended by the panel, good labour relations requires an employer to be held to this. A failure to comply with the rules may result in substantive unfairness.[27] In the case where another person has been promoted to the post then the unsuccessful candidate must show that this is unfair. And as Wallis AJ (as he then was) said in Ndlovu v Commissioner for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others:That will almost invariably involve comparing the qualities of the two candidates. Provided the decision by the employer is rational it seems to me that no question of unfairness arises [Footnotes omitted]

[28] The employee challenged the commissioners finding that his assertion that he performed better in the psychometric assessment was misleading and a simplistic approach to the complexities involved in the psychometric assessment. The basis for this challenge was that it was not supported by evidence and was not preceded by proper evaluation and analysis of the psychometric assessment results, especially when he failed to state what complexities of the results were.

Promotion

JA 140/2021

Mashaba v University of Johannesburg and Others (JA 140/2021) [2022] ZALAC 116 (18 October 2022)

[14]...The employer has a discretion to choose which one will be appointed. The court cannot interfere with that discretion unless it can be demonstrated that it was exercised capriciously or is vitiated by malice or fraud.[Department of Rural Development and Agrarian Reform v General Public Service Sectoral Bargaining Council and others [2020] 4 BLLR 353 (LAC) at para [23]. See also SAPS v Safety and Security Sectoral Bargaining Council and others unreported judgment case no P426/08 delivered on 27 October 2010 at para [41].

[15] The appointment and promotion of employees falls squarely within the domain of the employer, who has to effect the promotion in accordance with its requirements for the post. It is the employer who must select the best suitable candidate particularly where there is more than one candidate qualifying for the position.[SAPS v Safety & Security Sectoral Bargaining Council & others [2010] 8 BLLR 892 (LC) at paras [15] and [19] [20]; and Ndlovu v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation & Arbitration & others (2000) 21 ILJ 1653 (LC) at paras [11] [13].

[18] A promotion is a process commencing with the advertisement of the post followed by shortlisting and interviews. The interviewing panel makes recommendations to the employer to appoint a candidate they found to be suitable. In my view, it is highly improper and unfair for a candidate to let the process go to its finality without challenging it and only afterwards argue that the process was irregular.