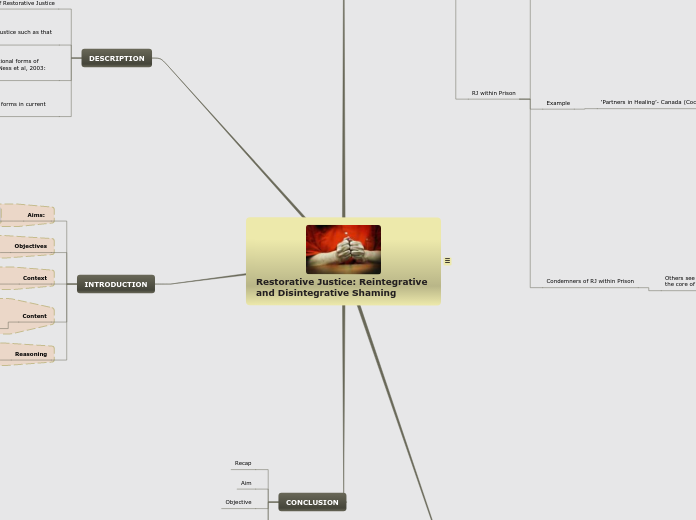

Restorative Justice: Reintegrative and Disintegrative Shaming

CRITICAL ANALYSIS

RESTORATIVE JUSTICE IN THEORY

The main philosophy of RJ is to work to resolve conflict and repair harm

this is achieved by encouraging those that have caused harm to acknowledge and understand the impact their actions have on the victim of the offence.

Criticism: Is it always possible to achieve 'reparation'.

Agreements are key outcomes in RJ conferences. However, there is a debate over the effectiveness of such agreements to reduce post-conference offending (see Hayes et al (2014) attached).

Restorative Justice also provides those who have suffered as a result of the offenders actions the opportunity to have what harm they have sustained acknowledged and for reparation to be made for the loss incurred.

RJ is a problem solving approach to crime which involves the parties themselves, and the community generally, in an active relationship with statutory agencies.

Justice is done in a way which places 'decisions about how best to deal with the offence on those most effected (Morris, 2002:598).

‘Crime, Shame and Reintegration’, (1989) by John Braithwaite

Braithwaite (1999: 6) suggests that it would be better to think of restorative justice as being about ‘restoring victims, restoring offenders and restoring the communities’ which are affected by a crime, with the parties determining what ‘restoration’ means in each circumstance. Braithwaite took up the issue of the conditions under which societal reactions increase crime (as labelling theorists contend) or decrease crime (as advocates of punishment predict).

Braithwaite (1989:69-83) believed that sanctions imposed by relatives, friends or a personal relative collectively have more effect on criminal behaviour than sanctions imposed by a remote legal authority. This basis for Braithwaite was taken from the results of a Government Social Survey conducted by Zimring and Hawkins (1973:192), which asked youth’s to rank what they saw as the most important consequences of arrest:

legal violations evoke formal attempts by the state and informal efforts by intimates and community members to control the misconduct

“all processes of expressing disapproval which have the intention or the effect of invoking remorse in the person being shamed and/or condemnation by others who become aware of the shaming” (p.9).

Government Social Survey by Zimring and Hawkins (1973) found, “while only 10% said ‘the punishment I might get’, was the most important consequence of arrest, 55% said either ‘What my family’ or ‘What my girlfriend’ would think about it.

He proposed that shaming could be defined into two distinct categories.

REINTEGRATIVE SHAMING

DISINTEGRATIVE SHAMING

Another 12% ranked ‘the publicity or shame of having to appear in court’ as the most serious consequence” (ibid:192).

Principles of RJ

According to Title (2011), the ‘Five R’s of RJ’ are:

Relationships

Respect

Responsibility

Repair

Reintegration

RJ s can function as a viable alternative to incarceration

Prison-based RJ programmes exist in the context of debates around whether the goals of imprisonment and RJ can be complementary

Some argue that imprisonment and RJ have the reintegration of offenders as a central goal (Aerston and Peters, 1998).

Advocates have argue that so long as RJ is developed only in community settings, outside the prison, it will be regarded as suitable only for young and minor offenders and their victims but (Edgar and Newell, 2006: 24-5).

RJ within Prison

Within prisons, using examples from the UK other countries, RJ has taken many forms:

Community service projects

Victim awareness/ empathy/ impact projects

Victim-offender groups/mediation/conferencing

Restorative adjudication and procedures

Prison communities of restoration

Subtopic

Example

‘Partners in Healing’- Canada (Cocker, 2015)

Aimed to promote RJ by running committees inside prison and recruiting volunteers from the community to participate.

The main goal was to increase the participants awareness of RJ and help prisoners gain an understanding of the effects of their crime(s). Three specific objectives being:

Provide increased opportunities for community engagement,

Support offenders as they prepare to be reintegrated into the community

Provide opportunities for victims to feel understood and heard.

Dilema's

Motive

Manifest motivations- Those that wanted to make amends and repair their relationships with others found the experience positive.

Latent motivations- Some chose to participate because they provided a ‘change of pace’ from the regular routine. One called it a ‘night out from the prison’ ie. Think they would obtain favourable conditions due to participation.

Issues

Some members stopped attending because they felt the meeting had strayed away from the original purpose and had become a waste of time.

Findings

From interviews, she concluded that those inmates chosen should be those who are ready to accept responsibility for what they had done and to learn more about the effects of their crimes.

Individuals who are not ready for the process can undermine it or create harms for other participants.

Condemners of RJ within Prison

Others see the goals of prison and RJ as antithetical and that the core of RJ challenges the underlying rational of prison

The only appropriate response is to divert offenders away from imprisonment and towards community-based programmes (Immarigeon, 2004).

Guidoni (2003) argues that rather than prisons being transformed in line with RJ principles, the more likely outcome is the temporary adoption of limited aspects of RJ, which are then used to add legitimacy to an institution which remains essentially punitive.

CRITICAL EVALUATION:

RESTORATIVE JUSTICE IN PRACTICE

RJ is frequently presented as innovative and thus to be differentiated from more established justice approaches (Morris and Young, 2000).

At one extreme, RJ is considered the 'third way', distanced from both Retribution and Rehabilitation (see for example Graef, 2000).

Shapland (2008) found that in randomised control trials of RJ with serious offences (robbery, burglary and violent offences) by adult offenders

The majority of victims chose to participate in face-to-face meetings with the offender, when offered by a trained facilitator

85% of victims who took part were satisfied with the process

RJ reduced the frequency of re-offending, leading to £9 savings for every £1 spent on restorative justice

Structural Obstacles

Prison culture limits to some extent the level of trust that can be built (Crocker, 2015).

Prison politics can intrude on the process.

Prisons alter the identity of their inmates which are diametrically opposed to the positive reconstructive identity which RJ aims to achieve.

Prison sub-cultures constantly pull offenders away from the ‘new worlds’ which RJ seeks to give them.

Non-coercive conflict resolution is extremely difficult in prison.

There are incentives to take part in RJ schemes without making any commitment to the ethos and goals of RJ.

RJ as an Alternative to Prison

Instead of warehousing offenders, shouldn't we be using what we know about the brain to help them rehabilitate?

THE NEUROSCIENCE OF RESTORATIVE JUSTICE BY DANIEL REISEL

DESCRIPTION

Definition of Restorative Justice

The theory of criminal Justice that defines crime as an act committed by a person against another person or community rather than an act against the state.

Provide an official definition of restorative Justice such as that offered by Marshall (1995:5).

A process whereby parties with a stake in a particular offence, collectively resolve how to deal with the aftermath of an offence and its implications for the future (Marshall, 1995:5).

RJ represents a distinct alternative to traditional forms of Justice administered by youth courts (Van Ness et al, 2003: 5).

Restorative Justice views crime as a violation of persons and relationships that require repair and restoration (Cornwell, 2007:5).

Justice is achieved in a way which places 'decisions about how best to deal with the offence on those most effected (Morris, 2002:598).

Restorative justice can take many different forms in current criminal Justice practice.

These are:

Peacemaking and Sentencing Circle (Canada)

Victim Offender mediation (North America and Canada)

Youth Offender Panels (United Kingdom)

Conferencing (United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, North America)

INTRODUCTION

Aims:

What is the question asking?

Objectives

How might you answer the question?

Context

In what context does the question relate to?

Content

What/Which research, studies, philosophies, theories, evidence have you analysed, evaluated, explored, discussed in an attempt to answer the question.

Reasoning

What was the reasoning behind these choices?

CONCLUSION

Recap

Aim

Objective

Main points of analysis

Main points of evaluation