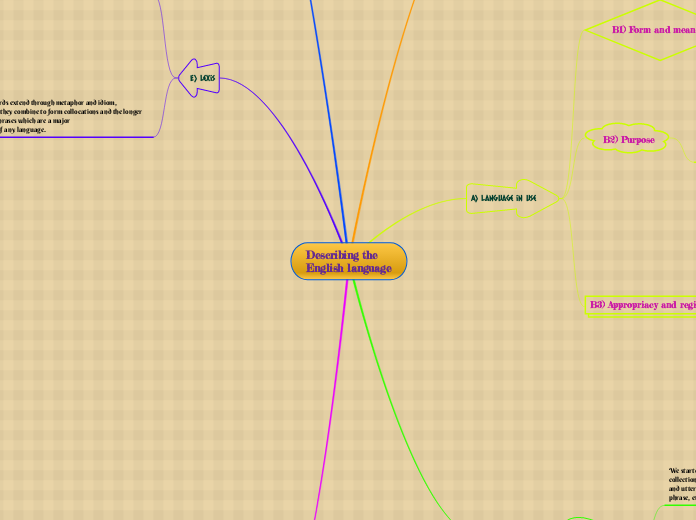

Describing the

English language

A) What we want to say

The language we speak or write is governed by a number of rules, informal speech is both similar to and very different from more formal written language.

Informal speech is both similar to and very different from more formal written language

A) Language in use

B1) Form and meaning

The issue that faces us is that the words we use and what they actually mean in the

context we use them, are not the same thing at all.

This same-form-different-meanings situation is surprisingly

unproblematic for language users since the context (situation) and co-text (lexis and grammar

which surround the form, such as eight o'clock, Look at John, etc.)

The choice of which future form to use from the examples above will depend not only on

meaning, but what purpose we wish to achieve.

B2) Purpose

Many years ago, the philosopher J L Austin identified a series of verbs which he called

performatives', that is verbs which do what those same words mean

B3) Appropriacy and register

A feature of language functions is that they do not just have one linguistic realisation;

Six of the variables which govern our choice are listed below:

•Setting: we speak differently . We often use informal and spontaneous language at home.

•Participants: the people involved in an exchange - whether in speech or writing - clearly affect the language being chosen.

•Gender: research clearly shows that men and women typically use language differently, when addressing either members of the same or the opposite sex..

•Channel: there are marked differences between spoken and written language. But spoken language is not all the same: it is affected by the situation we are in.

•Topic: the topic we are addressing affects our lexical and grammatical choices.

•Tone: another feature of the register in which something is said or written is its tone. This includes variables such as formality and informality, politeness and impoliteness.

C) Language as text and discourse

We started this chapter with four examples of texts - that is collections of words, sentences

and utterances (an utterance is a sentence, question, phrase, etc. in speech).

C1) Discourse organisation

In written English this calls for both coherence and cohesion.

For a text to be coherent, it needs to be in the right order - or at least make sense.

Grammar and vocabulary are vital components of language (as are the sounds of

English in spoken discourse), we also need to look at language at the level of text or discourse

(that is texts which are longer than phrases or sentences).

C2) Genre

One of the reasons we can communicate successfully, especially in writing, is because we have some understanding of genre. is to say that a genre is a type of written organisation and layout (such as an advertisement, a letter, a poem, a magazine article, etc.)

D) Grammar

There is a system of rules, in other words, which says what can come before what and which order different elements can go in. We call this system syntax.

Grammar can thus be partly seen as a knowledge of what words can go where and what

form these words should take.

D1) Choosing words

We have to take into account countable and uncountable nouns.

Verbs which are either transitive (they take an object),

intransitive (they don't take an object) or both. The verb herd (e.g. to herd sheep)

Verbs are good examples, too, of the way in which words can trigger the grammatical

behaviour of words around them.

Studying grammar means knowing how different grammatical

elements can be strung together to make chains of words.

The following diagram shows how

the same order of elements can be followed even if we change the actual words used and alter

their morphology.

E) Lexis

In this section we will look at what is known about lexis (the technical name for the vocabulary

of a language).

E1) Language corpora

One of the reasons we are now able to make statements about vocabulary with considerably more confidence than before is because lexicographers and other researchers are able to

analyse large banks of language data stored on computers.

How words extend through metaphor and idiom,

and how they combine to form collocations and the longer lexical phrases which are a major

feature of any language.

E2) Word meaning

The least problematic issue of vocabulary, it would seem, is meaning. for example polysemy

Another relationship which defines the meaning of words to each other is that oihyponymy,

where words like banana, apple, orange, lemon, etc. are all hyponyms of the superordinate

fruit. And fruit itself is a hyponym of other items which are members of the food family.

E3)Extending word use

They can also be stretched and twisted to fit different contexts and different uses.

E4) Word combinations

Collocations are words which co-occur with each other and which language users, through custom and practice, have come to see as normal and acceptable. It is immediately apparent that while some words can live together, others cannot.

F) The sounds of the language

In writing, we represent words and grammar through orthography. When speaking, on tne other hand, we construct words and phrases with individual sounds, and we also use pitcn change, intonation and stress to convey different meanings.

F1) Pitch

One of the ways we recognise people is by the pitch of their voice. We say that one person has a very high voice whereas another has a deep voice.

F2) Intonation

On it's own, pitch is not very subtle, conveying, as we have seen, only the most basic information about mood and emotion. But once we start altering the pitch as we speak

Intonation plays a crucial role in spoken discourse since it signals when speakers

have finished the points they wish to make, tells people when they wish to carry on with a turn

(i.e. not yield the floor) and indicates agreement and disagreement.

Intonation is a notoriously tricky area.

F3) Individual sounds

Words and sentences are made up of sounds (or phonemes) which, on their own, may not carry meaning, but which, in combination, make words and phrases.

Competent speakers of the language make these sounds by using various parts of the mouth (called articulators), such as the lips, the tongue, the teeth, the alveolar ridge (the flat little ridge behind the upper teeth), the palate, the velum (the flap of soft tissue hanging at the back of the palate, often called the soft palate) and the vocal cords.

Vowels are all voiced, but there are features which differentiate them. The first is the place in

the mouth where they are made. The second feature, which is easier to observe, is the position of the lips. For /a:/, the lips form something like a circle, whereas for /i:/, they are more

stretched and spread

F4) Sounds and spelling

Whereas in some languages there seems to be a close correlation between sounds and spelling,

in English this is often not the case.

A lot depends on the

sounds that come before and after them, but the fact remains that we spell some sounds in a variety of different ways, and we have a variety of different sounds for some spellings.

F5) Stress

The pronunciation of the words between the British and the United States lies in the emphasis they give to the words.

Words are often not pronounced as one might expect from their spelling. It is worth noticing, too, that when a word changes shape morphologically, the stressed

syllable may shift as well.