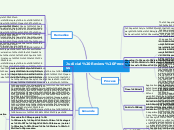

Judicial Review Process

Process

Exhaustion of Remedies

The applicant must first exhaust all other remedies available to them that can help them challenge the decision in question, before commencing Judicial Review. This might, for instance, include internal appeal or complaints procedures within the public body in question - R v Epping and Harlow General Comrs, ex Parte Goldstraw (1983)

Standing/Locus Standi

Individuals: Under s.31 Senior Courts Act 1981, the High Court can only hear applications for Judicial Review from those who have a 'sufficient interest' in the decision that is being challenged. In essence, the individual must have a 'particular interest' in the decision, and not be a mere 'busybody'. (Walton v The Scottish Ministers (2012))

Interest Groups: The applicant may not be an individual who is directly affected by the decision in question. Whether a 'group' of individuals have standing depends on the circumstances of the case. The court can take a range of matters into account when determining standing for interest groups. See: R v HM Inspectorate of Pollution, ex parte Greenpeace (No. 2) (1994), R v Secretary of State for the Environment, ex parte Rose Theatre Trust Co (1990).

Time Limit

Application for judicial review must be made within three months and 'promptly' (Civil Procedure Rules 54.5). In essence, the applicant can apply within three months, but act as if time is of the essence.

Public Body

Applicants can only review the acts of 'public bodies'. Usually this is straightforward - for instance, the body may be the NHS, or a Government department. However, if there is any uncertainty as to whether the body is 'public' in nature, the court may look at various factors, including:

- Whether the body exercises a 'public' function.

- Whether the bodyhas a 'statutory framework'.

- Whether it is 'governmental' in nature.

For more, see the Datafin (1987) case.

Ouster Clauses

An Act of Parliament may have formed the public body in question. Within the Act, there may be a section which prevents the body from being subject to judicial review.

These clauses are often interpreted strictly by courts, because preventing the review of a public body can be considered avoiding accountability and access to justice for applicants - see Anisminic Case (1968)

Remedies

Mandatory Order: The court may compel the body to perform their public duty in line with the law.

Prohibiting Order: The court prevents the body from making a decision that would be unlawful.

Quashing Order: The court 'quashes' (invalidates) the act of the public body.

Declaration: The court makes a declaration on the law surrounding the acts of a public body. For instance, in the Miller case (see the Brexit tab on moodle) the court made a declaration determining whether it should be Government or Parliament who should trigger Article 50.

Grounds

Illegality (Ultra Vires): The applicant may claim that the public body has acted in a way that is inconsistent with the powers conferred on it. An act may be ultra vires for a number of reasons, including the body improperly using its power (Padfield (1968)), or making an error of law (Anisminic (1968))

Legitimate Expectation: The public body may have made an express or implied 'promise'. In some instances, if that promise is broken, the court may quash the act that broke that promise.

Procedural Impropriety - Generally split into two categories: The right to fairness/natural justice; and a failure to follow procedure.

Natural Justice

Rule against bias: The public body may be subject to review if it makes biased decisions: see Porter v Magill (2001) - there must be "Real evidence" of bias.

Duty to give reasons: In some cases, the public body may be required to give reasons for its decisions. If this duty arises, then a failure to give reasons is a ground for review: see R v Civil Service Appeal Board ex parte Cunningham (1991) - In particular, the court stated that a decision that appeared 'unusual' would give rise to duty to provide reasons to the applicant.

Failure to Follow Procedure - As simple as it says: Where a minister fails to correctly follow procedures laid out in the Act granting him power, then there will be grounds for review.

Unreasonableness: The act may be "so unreasonable that no reasonable public body would have come to that decision"(Associated Provincial Picture Houses Ltd v Wednesbury Corp 1948)