What are the effects on immigrants in Canada, 1930 to present?

Japanese Canadian

Postwar community

In the 1950s, Japanese Canadians struggled to rebuild their lives but, now scattered across Canada, could not rebuild their communities. Scattered, and without contact during their youth with other Japanese Canadians, many of the Sansei speak English or French but little or no Japanese, and have only limited knowledge of Japanese culture, past or present.

Expulsion

Those who resisted the removal of Japanese Canadians were shipped to prisoner of war (POW) camps at Petawawa and Angler in Ontario

More than 8,000 were moved through a temporary detention centre at Hastings Park in Vancouver, where the women and children were accommodated in the Livestock Building.

On 25 February 1942, a mere 12 weeks after the 7 December 1941 attack by Japan on Pearl Harbor and Hong Kong, the federal Cabinet, at the instigation of racist BC politicians, used the War Measures Act to order the removal of all Japanese Canadians residing within 160 km of the Pacific coast.

Political

This outcome was not surprising given that the BC federal Liberal campaign slogan in the 1935 federal election had been: “A Vote for ANY CCF Candidate is a VOTE TO GIVE the CHINAMAN and the JAPANESE the same Voting Right that you have!”

In 1936 a new Nisei group, the Japanese Canadian Citizens League (JCCL), despairing of gaining the provincial vote, sought instead to gain the federal franchise.

Community development

To counteract the negative impacts of prejudice and their limited English ability the Japanese, like many immigrants, concentrated in ghettos. institutions — schools, hospitals, temples, churches, unions, cooperatives and self-help groups.

In the 1920s and 1930s, even well-educated Nisei who sought employment in business or the professions were unable to obtain employment outside the Japanese Canadian enclaves.

Japanese Canadians formed co-operative associations to market their produce and fish, and community and cultural associations for self-help and social events.

Excluded from Canadian society, Japanese Canadians before the Second World War congregated in enclaves and developed their own social, religious and economic institutions (see Residential Segregation).

History racsim

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the BC government denied logging licences to Asians and paid Asians only a fraction of the social assistance paid to Whites.

Labour and minimum-wage laws ensured that employers hired Asian Canadians only for menial jobs or farm labour, and paid them at lower pay-rates than Caucasians.

All Asians were denied the right to vote

passed a series of laws intended to force all Asians to leave Canada.

Japanese Canadians, both Issei immigrants and their Canadian-born children, called Nisei (second generation), have faced prejudice and discrimination.

Waves

Second wave

The second wave of Japanese immigration began in 1967, when immigration laws were amended and a point system was instituted. The point system was based on social and economic characteristics that favoured educated immigrants competent in English or French from industrialized cities. Many Japanese immigrants to Canada during this period worked in business, the service sector and skilled trades.

First wave

called Issei (first generation)

arrived between 1877 and 1928. Until 1907, almost all immigrants were young men

In 1908, Canada insisted that Japan limit the migration of males to Canada to 400 per year, arranging what was known as the Gentlemen’s Agreement with officials in Japan. As a result, most immigrants thereafter were women joining their husbands or unmarried women engaged to men in Canada.

In 1928, Canada further restricted Japanese immigration to 150 persons annually, a quota seldom met.

In 1940, immigration ceased after Japan allied itself with Canada’s Second World War enemies, Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Japanese immigration did not resume until the mid-1960s

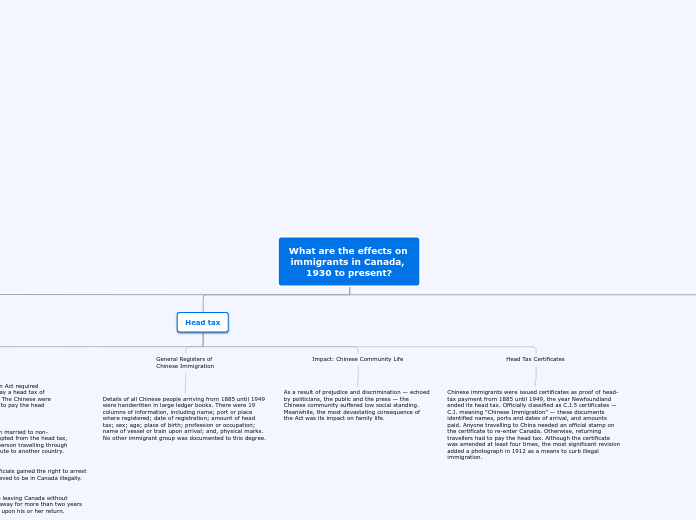

Head tax

Head Tax Certificates

Chinese immigrants were issued certificates as proof of head-tax payment from 1885 until 1949, the year Newfoundland ended its head tax. Officially classified as C.I.5 certificates — C.I. meaning “Chinese Immigration” — these documents identified names, ports and dates of arrival, and amounts paid. Anyone travelling to China needed an official stamp on the certificate to re-enter Canada. Otherwise, returning travellers had to pay the head tax. Although the certificate was amended at least four times, the most significant revision added a photograph in 1912 as a means to curb illegal immigration.

Impact: Chinese Community Life

As a result of prejudice and discrimination — echoed by politicians, the public and the press — the Chinese community suffered low social standing. Meanwhile, the most devastating consequence of the Act was its impact on family life.

General Registers of Chinese Immigration

Details of all Chinese people arriving from 1885 until 1949 were handwritten in large ledger books. There were 19 columns of information, including name; port or place where registered; date of registration; amount of head tax; sex; age; place of birth; profession or occupation; name of vessel or train upon arrival; and, physical marks. No other immigrant group was documented to this degree.

Chinese immigration act

The head tax was in effect for 38 years (1885–1923) and approximately 82,000 Chinese immigrants paid nearly $23 million in tax.

In 1921, Chinese people leaving Canada without registering and anyone away for more than two years had to pay the head tax upon his or her return.

In 1917, immigration officials gained the right to arrest any Chinese person believed to be in Canada illegally.

In 1887, Chinese women married to non-Chinese men were exempted from the head tax, as well as any Chinese person travelling through Canada by railway en route to another country.

The Chinese Immigration Act required that Chinese migrants pay a head tax of $50 to come to Canada. The Chinese were the only group who had to pay the head tax.

The Chinese head tax was levied on Chinese immigration to Canada between 1885 and 1923, under the Chinese Immigration Act (1885). With few exceptions, Chinese people had to pay $50 (later raised to $100, and then $500) to come to Canada.

Immigration since 1930

Time order

Year-by-year change

1931 : Census. The population of Canada was 10,376,786, of whom 22% were immigrants (i.e. born outside Canada). 44% of immigrants were female (but only 14% of Asian immigrants), 67% had been in Canada more than 10 years. 49% of immigrants were born in the British Isles, 15% in the U.S., 14% in Central Europe and less than 3% in Asia.

1941 : Census. The population of Canada was 11,506,655, of which 17.5% was composed of immigrants (i.e. born outside Canada). 45% of the immigrant population was female. Only in the case of immigrants from the U.S. were there more women than men. 90% of immigrants had been in Canada for 10 years or more (33% for more than 30 years). 44% of immigrants were born in the British Isles, 14% in the U.S., 7% in Poland and 5% in Russia. There were 29,095 immigrants from China (of whom only 1,426 were women), 9,462 from Japan and 5,886 other "Asians". No African countries are listed. Women immigrants were less likely to be rural than men. There were 170,241 Jews, 34,627 Chinese and 22,174 "Negroes". 71.5% of the foreign-born were naturalized citizens (8% of the Chinese-born, 35% of the Japanese-born). 97.7% of the population was of European origin.

1961 : Census. Of the Canadian population of 18,238,247, 15.6% (2,844,263) were immigrants (i.e. born outside Canada). 48% of the immigrant population was female (but 52% of immigrants from the UK, 54% of those from the U.S. and only 38% of those from "Asiatic countries"). 58% of immigrants had been in Canada for 10 years or more. 34% of immigrants were from the UK, 51% from other European countries (Italy by itself represented 9%), 10% from the U.S., 2% from "Asiatic countries", 0.6% from "other countries" (which includes all of Africa apart from South Africa). 63% of immigrants were Canadian citizens. 96.8% of the population was European.

1971 : Census. Of the population of 21,568,310, 15.3% (3,295,530) were immigrants (i.e. born outside Canada). 68% of immigrants had been in Canada for 10 years or more. 49.7% of immigrants were female.79% of immigrants were born in Europe (28% in the UK, 12% in Italy, 6% in Germany, 5% each in Poland and the USSR). "Asiatic countries" were the birthplace for under 4% of immigrants. All African countries are grouped under "other countries" (2% of immigrants). In terms of "ethnic group", 44.6% were from the British Isles, 28.7% French, 6% German, 3.4% Italian, and 2.7% Ukrainian. There were 118,815 Chinese, 67,925 "East Indian", 37,260 Japanese, 34,445 "Negro", 28,025 West Indian and 26,665 "Syrian-Lebanese". 97% of the population was of European origin.

1981 : Census. Of the total population of 24,083,500, 16% were immigrants (i.e. born outside Canada). 51% of immigrants were female. 67% of immigrants were born in Europe, 14% in Asia, 8.5% in North or Central America, 4.5% in the Caribbean, and 2.7% in Africa. Females made up 47% of those born in Italy, 48% of those born in Africa, 51% of those born in China, 53% of those born in North or Central America, 55% of those born in the Caribbean, and 58% of those born in the Philippines. 66% of immigrants had been in Canada for at least 11 years. 69% of immigrants were Canadian citizens. In terms of ethnic origins, 92% of the population declared a single ethnic origin. 86% of population had a single European ethnic origin (40% British, 27% French). "Asia and Africa" (listed as a single entry) accounted for 3%, "Far East Asia" 1.7%, "North and South America" 2%.

1991 : The Census. Of the total population of 26,994,045, 16% (4,342,890) were immigrants (i.e. born outside Canada). 51% of immigrants were female. (57% of immigrants from U.S., 56% of Caribbean immigrants, but only 46% of African immigrants.) 72% of immigrants had been in Canada more than 10 years. 54% of immigrants were born in Europe, 25% in Asia, 6% in U.S., 5% in the Caribbean and 4% in Africa. While 32% of the total population lived in Montreal, Toronto or Vancouver, 57% of the immigrant population did. 81% of immigrants eligible to become Canadian citizens had done so. 71% of the total population declared a single ethnic origin (66% gave a single European origin, while Asian, Arab and African single origins together made up 6%).

1930 : Issued prohibiting the landing of "an immigrant of an Asiatic race", except wives and minor children of Canadian citizens (and few Asians could get citizenship).

1946 : Order in Council issued allowing Canadian citizens to sponsor brothers and sisters, parents and orphaned nephews and nieces.

1946 : Canadian Citizenship Act adopted, creating a separate Canadian citizenship, distinct from British (Canada was the first Commonwealth country to do so).

1947 : Chinese Immigration Act repealed, following pressure, formed by church and labour groups. Chinese immigration was henceforth regulated by the 1930 rules for "Asiatics" which allowed only the sponsorship of wife and children by Canadian citizens.

1947 : Prime Minister Mackenzie King made a statement in the House outlining Canada's immigration policy.

1961 : 71,689 immigrants arrived - the lowest level since 1947, and a reflection of the economic recession.

1962 : Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Ellen Fairclough implemented new Immigration Regulations that removed most racial discrimination, although Europeans retained the right to sponsor a wider range of relatives than others.

1966 : A white paper was tabled, recommending an immigration policy that was "expansionist, non-discriminatory, and balanced in reconciling the claims of family relationship with the economic interest of Canada".

1967 : The Immigration Appeal Board Act was passed, giving anyone ordered deported the right to appeal to the Immigration Appeal Board, on grounds of law or compassion.

1970 : Immigration from Asia and the Caribbean represented over 23% of the total, compared with 10% four years previously.

1976 : New Immigration Bill tabled. It identified objectives for the immigration program and forced the government to plan for the future, in consultation with the provinces. Immigrants were divided into four categories: independents, family, assisted relatives and humanitarian. The Refugee Status Advisory Committee was created. The "prohibited" categories were replaced with "inadmissible" categories, among which were no longer to be found epileptics, imbeciles, persons guilty of crimes of moral turpitude, homosexuals and people with tuberculosis. Deputy Minister Allan Gotlieb described the legislation as "a beautiful piece of work - logical, well-constructed, liberal, and workable". The accompanying Immigration Regulations revised the points system and created the Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program.

1989 : Bills C-55 and C-84 came into effect, introducing many changes to immigration law, a new refugee determination system and the Immigration and Refugee Board.

1993 : Amendments to the Immigration Regulations cancelled the sponsorship required for "assisted relatives" and reduced the points awarded them, making it more difficult for family members (other than nuclear family) to immigrate to Canada.

Significance moment

In the 19th century, the movement of individuals and groups to Canada was largely unrestricted, except for the ill, the disabled and the poor — groups targeted by the first Immigration Act, passed in 1869.

In 1930-31, the Canadian government responded to the Great Depression by applying severe restrictions to entry. New rules limited immigration to British and American subjects or agriculturalists with money, certain classes of workers, and immediate family of Canadian residents. Since many immigrants came to Canada as farmers or labourers, they were particularly vulnerable during the economic downturn.

In 1952, a new Immigration Act continued Canada's discriminatory policies against non-European and non-American immigrants. However, in 1962 Ottawa ended racial discrimination as a feature of the immigration system. In 1967, a points system was introduced to rank potential immigrants for eligibility.

The new immigration regulations introduced in 1962 eliminated overt racial discrimination from Canadian immigration policy. Skill became the main criteria for determining admissibility rather than race or national origin. The classes of sponsored immigrants were expanded so that all Canadian citizens and permanent residents could sponsor relatives for immigration. However, an element of discrimination remained as only Canadian immigrants from preferred nations in Europe, the Americas and select countries in the Middle East were permitted to sponsor children over the age of 21, married children and other members of their extended family.

In a statement to the House of Commons on 8 October 1971, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau announced multiculturalism as an official government policy. Multiculturalism was intended to preserve the cultural freedom of individuals and provide recognition of the cultural contributions of diverse ethnic groups to Canadian society. The government committed to support multiculturalism by assisting cultural groups in their development, assisting individuals in overcoming discriminatory barriers, encouraging intercultural exchange and assisting immigrants in learning French or English.

The Immigration Act of 1976 represented a significant shift in Canadian immigration legislation. It was the first immigration act to clearly outline the fundamental objectives of Canadian immigration policy, define refugees as a distinct class of immigrants and impose a mandatory responsibility on the government to plan for the future of immigration. Nearly all of the committee’s recommendations were accepted by the government and incorporated into the Immigration Act introduced in 1976. The preamble of the new measures clearly set out the objectives of Canadian immigration law, including family reunification, non-discrimination, concern for refugees and the promotion of Canada’s economic, social and cultural goals.

By 1980, five classes of immigrants had been established for entry to Canada: Independent (people applying on their own); Humanitarian (refugees and other persecuted or displaced people); Family (having immediate family already living in Canada); Assisted Relatives (distant relatives, sponsored by a family member in Canada); and Economic (people with highly desirable employment skills, or those willing to open a business or invest significantly in the Canadian economy).

During the 1980s, policy makers instituted a program to encourage business people and entrepreneurs to immigrate to Canada, bringing their managerial skills and financial capital in order to create additional employment opportunities. Many immigrants have since brought substantial capital and jobs to Canada. From 1983 to 1996, approximately 400,000 Chinese from Hong Kong were admitted to Canada under the economic class rules, following the handover of Hong Kong from Britain to China. The Hong Kong immigrants brought billions of dollars worth of investments to Canada.

In 2001, after the September 11 terrorist attacks on the United States, Canada replaced its 1976 Immigration Act with the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act. The new Act, which came into force in 2002, maintained many of the principles and policies of the previous one, including the various classes of immigrants. It also extended the family class to include same-sex and common-law relationships. Most importantly, the 2001 Act gave the government wider powers to detain and deport landed immigrants suspected of being a security threat. In 2002, Canada and the US banned the practice of allowing migrants to enter one country on a travel visa, and claim refugee status at the border of the other (via the Canada-United States Safe Third Country Agreement).