MOVE ON TO EXPLORE HISTORICAL AND CONTEMPORARY CONCEPTIONS OF CHILDHOOD THROUGH KEY DEVELOPMENTS IN THE SOCIAL, LEGAL, MORAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT OF YOUTH

Social Constructions of Childhood

The question covers a number of central concerns. These are:

This map relates to the compulsary Section A of the exam, specifically question 1. It aims to outline the historical origins of ‘Youth’ and ‘juvenile delinquency’ in regards to the exploration of the discovery of ‘adolescence’ as a separate age of man and the determination as to whether both concepts are a historical or social construction.

It is both these aspects, the historical and social construction of childhood that form the backdrop of the question, more importantly the institutional framing of 'youth' and the social responses to it.

This means that the important characteristics of something, such as childhood, health and other forms of deviance are created and influenced by the attitudes, actions and interpretations of members of society.

Societies are individual in the way they have different social constructions, childhood is a important feature in some societies but doesn't really exist in others. In contemporary Britain and in most western societies people take it for granted that children are different from adults. Children are viewed as innocent and vulnerable who need protecting from the dangers of the adult world. We view childhood as a completely different period of time away from the adult life. As a result adults have to a extent constructed a “separate world” for children in the way.

Children are protected from adult dangers by laws (e.g. Negligence)

They have cheaper travel and special foods, clothes, toys

Special areas designed only for children (e.g. Indoor play areas)

Special arrangements made for them by the state like schools and child benefits.

We design theses features to protect children in their best interest as a result of children’s “natural biological immaturity”, therefore, society/adults construct childhood.

CONCLUSION

Main points of critical evaluation

Main points of critical analysis

Objective

Aim

Recap

INTRODUCTION

DESCRIPTION

Age-crime curve

The age- crime is one example of how the interlinking between youth and crime can be demonstrated

Age appropriate expectations

Society places expectations on young people as well as the expectations of parents, teachers. this creates a degree of strain on the young persons life.

an examination of the social and legal responses to youth crime

the interlinking between youth and crime can be evidenced by social and legal responses to youth crime both historically and contemporarily

Inextricable link between youth and crime

we automatically perceive our younger generations to be out and out delinquent

Definition of Youth

Provide an official/unofficial definition

COMPARE/CONTRACT

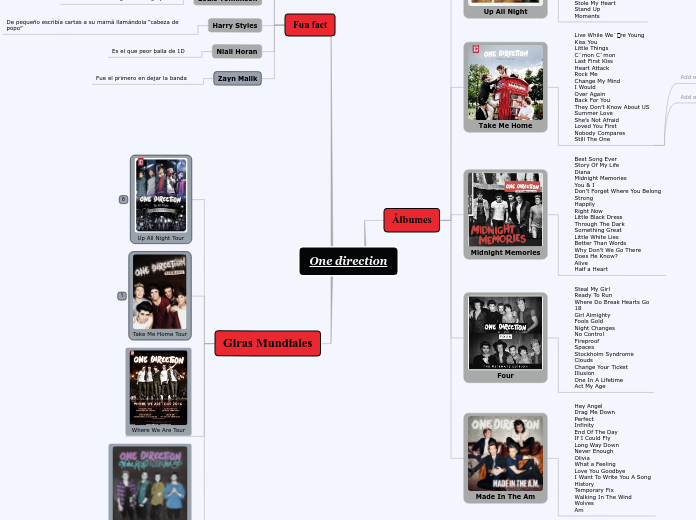

CONTEMPORARY CONCEPTIONS OF CHILDHOOD

Subtopic

The type of reports that make the headlines in the local press relate to anti social youths which too has grew to acquire symbolic stature in recent years.

This occured in parallel with heightened public concern regarding delinquency but only this time, the focvus has been on anti social behaviour as opposed to hooliganism

Such individuals are still experiencing increasing economic and leisurely independence as a result of the current recession

Attention is still bring paid to the perceived problem of young males forming street gangs

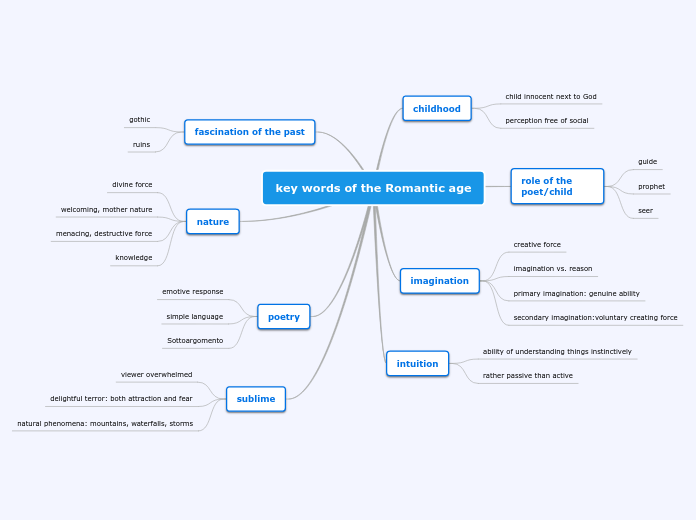

HISTORICAL CONCEPTIONS OF CHILDHOOD

This plethora of crime, defined as displays of public deviance, rowdiness, drunkenness had been termed ‘hooliganism’ and as such had made headlines in the local press and within a few years grew to acquire symbolic stature.

This occured in parallel with heightened public concern regarding delinquency and hooliganism.

Such individuals were experiencing increasing economic and leisurely independence

Attention was paid to the perceived problem of young males forming street gangs.

Main topic

CRITICAL EVALUATION: the social, legal, moral conceptions of childhood contemporarily

ARE THERE CONSEQUENCES FOR YOUTH FROM SUCH IDEOLOGIES?

Brown (2005:13) suggests, “this institutional framing of childhood within the school and reformatory has had long and profound consequences for the interlinking of youth and crime.”

Regulation

The extension of the period of childhood dependency through a number of legislative and institutional changes

It was against this very backdrop that a construction of youth and adolescent rather than childhood; and a reconstruction of juvenile delinquent were to take place.

Criminalisation

the development of more sophisticated surveillance techniques such as philanthropic schooling and policing, made children more problematic and visible.

As in contemporary society, the complex insecurities of the era came to bear upon the young, but this time on ‘youth’, opposed to ‘childhood’.

Although, Hendricks points out, the history and creation of delinquency and the history and creation of education are separate and different in many respects (Hendricks, 1990:45), the ideological origins of both forms of social regulation are similar.

HISTORY AND CREATION OF EDUCATION

Both are concerned with the practical threat of the unregulated child to the preservation of the social order.

Both view social and physical regulation as vital to both the moral well being of the child and the moral well being of society.

HISTORY AND CREATION OF DELINQUENCY

Both focus on the special nature of the child,

Legal Responses to youth and crime

Industrial Schools Act, 1857.

Marks a watershed in the transition to education and schooling for the masses.

Youthful Offenders Act, 1854

For the first time, ‘juvenile delinquency’ had been recognised legislatively, ‘as a distinct social phenomenon’.

Hand in hand, the Schooled child and the Delinquent child began to form.

Factory Act of 1833

Cited as the cut-off point of these social developments. Enforcement of the act prevented the employment of children under 9 and limited working hours for those aged between 9 and 13.

Social reactions to youth and crime

Due to the following legislative reform, children were viewed as the urban 'scurge' in inducstrialised towns and cities

The children of the working classes were seen as the biggest social threat.

Those of the Whig Tradition sought to save children from the degradation of factory life.

The notion of the Romantic child and all it stood for was seen as being under siege from the brutalization of children in the work place.

CRITICAL ANALYSIS: the social and legal and moral conceptions of childhood historically

FROM VICTIM TO THREAT

As the notion of childhood evolved, the idea that children were a responsibility and children were creatures who possessed the capacity for good and evil. Thus discipline was required to ensure that the former predominated over the latter.

Differing versions of childhood are identified as being reflective of the social conditions of the time rather than as natural or intrinsic qualities of a universal state of childhood.

THE CONSTRUCTION OF CHILDHOOD

Hendrick (1990: 37) identifies no less than five versions of childhood which were articulated during the Victorian era:

The Romantic child, the Evangelical child, the Factory child the Delinquent child and the Schooled child.

THE TREATMENT OF CHILDREN POST ENLIGHTENMENT

What has been important in the construction of childhood was the emergence of schooling and the changes and developments of family relationships during the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries.

In Aries view, it is only since this time that we have become preoccupied with the social moral and sexual development of young people.

TREATMENT OF CHILDREN PRE-ENLIGHTENMENT

For most of the eighteenth century (1700s) there was no concept of childhood in any recognizable modern sense. In other words, children tended to be expected to pass straight from physical dependence to something close to adulthood.

The period of physical dependence was taken to last up to about age 7-10. After that most children were expected to work adult hours ... and if convicted of a crime were held fully responsible and punished as adults.

In Britain and France the 1770s saw the gradual rise of the concept of an intermediate stage between physical dependence (infancy) and adulthood, namely childhood. The first books written specifically for children and some children's clothing began to appear for the first time. This development was largely confined to the middle classes, and for the poor it had to wait until well after 1850. The concept of adolescence - that is, a period between childhood and adulthood - is even more recent.

I've deliberately avoided mentioning the Enlightenment, as the beginnings

“Children were mixed with adults as soon as they were considered capable of doing without their mothers or nannies, not long after a tardy weaning (in other words at about the age of seven) (Aries, 1973:395).

Typically attributed to the work of Philippe Aries and his work, Centuries of Childhood (1973). He was of the view that the notion of ‘childhood’ as we know it contemporarily, was absent in medieval societies.