Labour Law cases decided in the South African Courts (Highlights and updated 1997 to December 2021 [copyright: Marius Scheepers/8]).

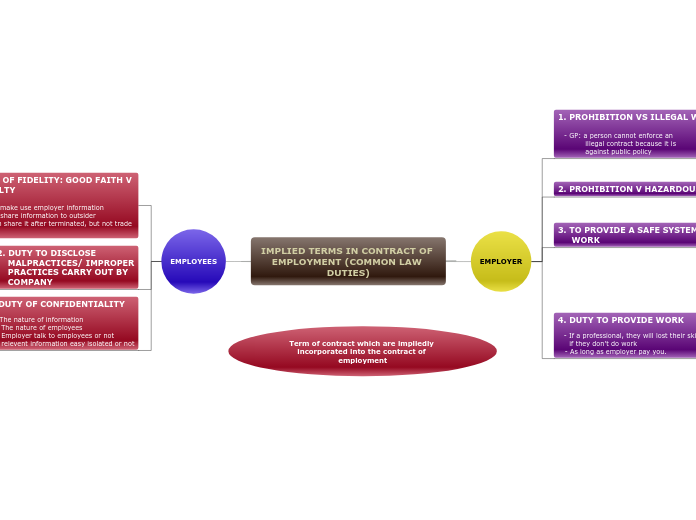

Employment and Conditions: Employment and Conditions: Agreement, Conditions of employment, Contract, Constructive dismissal, Contract of employment, Employee, Employment, Labour Broker, Legal persona,

Condition of employment

pension fund benefit

PA10/18

Zono v National Commissioner of Correctional Services N.O and Others (PA10/18) [2020] ZALAC 18; [2020] 9 BLLR 923 (LAC) ; (2020) 41 ILJ 2447 (LAC) (18 May 2020)

The Labour Court held that the determination of the appellants pensionable service in terms of the Rules of the GEPF is not a matter concerning a contract of employment. It is rather a matter concerning the interpretation and application of the Rules of the GEPF, which in this instance form a contract between the appellant and the GEPF.

No contractual dispute between employer and employee as contemplated in s 77(3) of the Basic Conditions of Employment Act- Labour Court not having jurisdiction

changes effected to the terms and conditions of the employment contract; tacit term in the contracts of employmen; long-standing practice and yearly custom did not form an employment condition

JR 580/2015

Health and Others Services Personnel Trade Union of South Africa (HOSPERSA) and Another v Mec-Free State Province and Others (JR 580/2015) [2019] ZALCJHB 53 (15 March 2019)

Unitrans Supply Chain Solutions (Pty) Ltd v SA Transport and Allied Workers Union and Others (2014) 35 ILJ 265 (LC) at para 13

[9] Aligned to the above enquiry however is whether what is alleged to have been changed falls squarely within the ambit of part and parcel of the terms and conditions of employment of the Dentists contract of employment[5].

See Ram Transport SA (Pty) Ltd v SATAWU and Another [2011] JOL 26805 (LC); Johannesburg Metropolitan Bus Services (Pty) Ltd v SAMWU and Others [2011] 3 BLLR 231 (LC);)

In determining this issue, the Courts have further drawn caution that a distinction ought to be drawn between a work practice as it exists and a term and condition of employment[6].

See A Mauchle (Pty) Ltd t/a Precision Tools v NUMSA [1995] 4 BLLR 11 (LAC); Apollo Tyres South Africa (Pty) Ltd v National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) and Others [2012] 6 BLLR 544 (LC)

This is premised on the basic principle that whilst the terms and conditions of employment cannot merely be changed at the whim of the employer, work practices on the other hand are by their nature subject to the employers prerogative[7].

[12] The applicants case was that commuted overtime had resulted in a tacit terms to their contracts of employment, which could not be overridden by the Departments Policy as implemented from 1 April 2014. As I understood the argument, the applicants rely on a tacit term based on a long-standing practice in regards to commuted overtime. In CEPPWAWU obo Konstable & others v Safcol[[ 2003] 3 BLLR 250 (LC). See also Edcon Ltd v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others [2017] 4 BLLR 391 (LC); (2017) 38 ILJ 1660 (LC] the Court held that a long-standing practice and yearly custom did not form an employment condition, unless the parties intention was to create a contractual right.

[15] The above lapses and omissions to comply with the provisions of the Policy in my view could not have created a tacit term in the contracts of employment of the Dentists for a variety of reasons, including that the Department is enjoined to manage public finances in accordance with the provisions of the PFMA and other strict Treasury Regulations.

Arbitration clause

J3701/18

Gama v Transnet SOC Limited and Others (J3701/18) [2018] ZALCJHB 348 (19 October 2018)

Mmethi v DNM Investment CC t/a Bloemfontein Celtics Football Club (2011) 32 ILJ 659 (LC) at para 17.

In short the principle in our law is that a clause in an agreement, as is the case in the present matter, which provides for a dispute to be referred to arbitration does not preclude a party from initiating court proceedings to have the dispute adjudicated by the court. What an arbitration clause however does is that it obliges the parties in the first instance to refer the dispute to arbitration. As stated earlier a party seeking to invoke and rely on the arbitration clause in the agreement must request a stay of such proceedings, pending the determination of the matter by an arbitrator. The court retains discretion whether or not to entertain the matter or hold the parties to their agreement and order them to resolve their dispute in terms of their agreement but retain the supervisory power over the arbitration process.'

Lufuno Mphaphu/i and Associates (Pty) Ltd v Andrews and another 2009 (6) BCLR 527 (CC) at para 219.

The decision to refer a dispute to private arbitration is a choice which, as long as it is voluntarily made, should be respected by the courts...'

Bonus

JR1249/16

Trans Caledon Tunnel Authority SOC Limited v Bleeker and Others (JR1249/16) [2018] ZALCJHB 261 (15 August 2018)

[20] Also, without prior notice, Ms Bleeker could not have known that she was going to be held responsible for the overall performance of the organisation, including the fruitless and wasteful expenditure. At least, the applicant ought to have afforded Ms Bleeker an opportunity to be heard prior to taking the final decision not to pay her bonus, a well-entrenched benefit defined in Apollo Tyres South Africa (Pty) Ltd v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others[[2013] 5 BLLR 434 (LAC) at para 50.] as an existing advantages or privileges to which an employee is entitled as a right or granted in terms of a policy or practice subject to the employers discretion. Even though the employer has a discretion not to pay a bonus, that discretion must be exercised judiciously. In this instance, Ms Bleeker was presented with a fait accompli.[21] In the premise, it is my view that the applicants decision not to pay Ms Bleeker her performance bonus for the financial year 2014/2015 is arbitrary, capricious and inconsistent with the constitutional imperatives.[Supra at paras 42 and 53. See also NEHAWU v University of Cape Town and Others 2003 (2) BCLR 154 (CC) at para 34.] The commissioner cannot be faulted in her finding in that regard.

unilatiral change

J1833/18

Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union v Anglo American Platinum Ltd and Others (J1833/18) [2018] ZALCJHB 238; [2018] 11 BLLR 1110 (LC); (2018) 39 ILJ 2280 (LC) (2 July 2018)

[31] A unilateral change to a contract of employment, as with any contract, ordinarily amounts to a breach of the contract and affords the aggrieved party the contractual remedies of specific performance or cancellation and damages (see Abrahams v Drake and Scull Facilities Management (SA) Pty Ltd (2012) 33 ILJ 1093 (LC)).

[32] As a general rule, an employer who wishes to effect changes to an employees terms and conditions of employment is required to obtain the employees consent. This is ordinarily effected by agreement with the individual concerned. Where the employee is represented by a bargaining agent in the form of a trade union, any changes to terms and conditions are regulated at a collective level and must necessarily be effected through the process of collective bargaining. In general terms, that process must be exhausted before any unilateral change can be made by the employer which at this stage, subject to the protection granted by s 64(4) of the LRA, constitutes a legitimate exercise of economic power.

Natal Joint Municipal Pension Fund v Endumeni Municipality 2012 (4) SA 593 (SCA). At para 18

Interpretation is the process of attributing meaning to the words used in a document, be it legislation, some other statutory instrument, or contract, having regard to the context provided by reading the particular provision or provisions in the light of the document as a whole and the circumstances attendant upon its coming into existence. Whatever the nature of the document, consideration must be given to the language used in the light of the ordinary rules of grammar and syntax; the context in which the provision appears; the apparent purpose to which it is directed and the material known to those responsible for its production. Where more than one meaning is possible each possibility must be weighed in the light of all these factors. The process is objective, not subjective. A sensible meaning is to be preferred to one that leads to insensible or unbusinesslike results or undermines the apparent purpose of the document. The 'inevitable point of departure is the language of the provision itself', read in context and having regard to the purpose of the provision and the background to the preparation and production of the document.

[44] Taking all of these instruments into account, in my view, Rusplats retains the prerogative in terms of the contracts of employment of each of the unions members to determine the provident fund to which its employees are required to belong. That being so, Rusplats did not breach the terms of the contracts when it required the unions members to join Old Mutual.

[45] To the extent that the union avers, as it does in the founding affidavit, that a change of retirement fund is a change to the term and conditions of an employment contract which requires at the very least proper and transparent consultations prior to any changes being made, it follows from the above finding that Rusplats was in law not required to consult with the union before implementing the change. The subject of the change cannot give rise to any legal obligation to consult. What matters in contractual terms is whether the employer is permitted to effect the change without securing the employees prior consent. For the reasons recorded above, in this instance, it is.

[54] ...The LRA does not compel bargaining, even less so does it require any party to a collective bargaining process to bargain in good faith. The absence of any statutory duty to bargain in good faith was a conscious policy choice. The model that finds expression in the LRA is one which allows parties, through the exercise of power, to determine their own arrangements. It avoids the rigidities that might be introduced by way of judicial intervention should an obligation to bargain in good faith be legally enforceable (see the Explanatory Memorandum published in (1995)16 ILJ at 292). This court has on numerous occasions held that it will not subject the conduct of collective bargaining partners to scrutiny, unless they act unlawfully.

SA Municipal Workers Union & another v SA Local Government Association & others (2010) 31 ILJ 2178 (LC), this court said (at paragraph 16 of the judgment)

The LRA introduced a voluntarist system of collective bargaining, a system in which neither this court (nor any other court or tribunal) is empowered to scrutinize bargaining conduct or make pronouncements on the good faith or otherwise exhibited by the any of the parties to collective bargaining

[56] In short: in the absence of a legally enforceable duty to bargain in good faith, this court is not empowered to subject the lawful acts of collective bargaining partners to scrutiny by reference to any standard of good faith.

probation and fixed term contracts

J 867/15

Mahasha v BT Interior DSGN (PTY) LTD (J 867/15) [2018] ZALCJHB 438 (8 June 2018)

[17] Effectively the Applicant is faced with a task of establishing that she was indeed a party to a contract that was to run for 31 months prior to canvassing its breach and the remedies. To this end and based on what is placed before the Court which is indeed and by and large of common cause in this respect, the Applicant has not attempted to demonstrate this as her case was solely focused on the last day of the 31 months period without any certainty about the first. In essence it cannot be said that the Applicant is entitled to a claim for damages under a contract which its endurance was subject to successful completion of probation.

Johnson & Johnson v Chemical Workers Industrial Union (1999) 20 ILJ 89 (LAC) and again on Fedlife Assurance Ltd v Wolfaardt [2002] 2 ALL SA295 (A).

Since the Respondent did not afford the Applicant an opportunity to be assessed, termination of her contract before the end of the probation period coupled with its failure to proffer a cogent reason, the Respondent should as such be found to be in breach of the contract. The Applicant should under the circumstances be awarded damages as prayed for.

Grievance: dismissal for rising. Automatically unfair dismissal: applicant exercising her rights

JS581/15

Garnevska v DBT Technologies (Pty) Ltd t/a DB Thermal (JS581/15) [2018] ZALCJHB 23 (26 January 2018)

[47]Evidence presented before me in respect of charge 2 clearly indicates that the respondent reacted to the grievance that the respondent had lodged whereby she was exercising her rights, and most importantly the evidence of Mr Kruger as conceded that the decision to call the applicant before a disciplinary hearing and what led to her dismissal was the outcome of the grievance hearing. As I have mentioned that the outcome therein suggests nothing and/or raises the allegations in charge 2. In addition to the above, I have taken into account the evidence of Ms Govender that she was only asked in March2015 about an incident that took place in April2014, clearly, this came about as a result of the applicant exercising her rights.

National Union of Public Service and Allied Workers obo Mani and others v National Lotteries Board (Mani) (2014) 35 ILJ 1885 (CC)

the court would determine whether, upon an evaluation of all the evidence, was thedominantormost likely cause of the dismissal(Own emphasis)

SA Chemical Workers Union & Others v Afrox Ltd (1999) 20 ILJ 1718 (LAC). Cited in Kroukam.

The enquiry into the reason for the dismissal is an objective one, where the employers motive for the dismissal will merely be one of a number of factors to be considered. This issue (the reason for the dismissal) is essentially one of causation and I can see no reason why the usual two fold approach to causation, applied in other fields of law should not also be utilized here . The first step is to determine factual causation: was participation or support, or intended participation or support, of the protected strike a sine qua non (or prerequisite) for the dismissal? Put another way, would the dismissal have occurred if there was no participation or support of the strike? If the answer is yes, then the dismissal was not automatically unfair. If the answer is no, that does not immediately render the dismissal automatically unfair; the next issue is one of legal causation, namely whether such participation or conduct was the main or dominant, or proximate, or most likely cause of the dismissal. There are no hard and fast rules to determine the question of legal causation (compare S v Mokgethi at 40). I would respectfully venture to suggest that the most practical way of approaching the issue would be to determine what the most probable inference is that may be drawn from the established facts as a cause of the dismissal, in much the same way as the most probable or plausible inference is drawn from circumstantial evidence in civil cases. It is important to remember that at this stage the fairness of the dismissal is not yet an issue Only if this test of legal causation also shows that the most probable cause for the dismissal was only participation or support of the protected strike, can it be said that the dismissal was automatically unfair in terms of s 187(1)(a)? If that probable inference cannot be drawn at this stage, the enquiry proceeds a step further.

Cooperand Another v Merchant Trade Finance Ltd (474/97) [1999] ZASCA 97 (1 December 1999).

It is not incumbent upon the party who bears the onus of proving an absence of an intention to prefer to eliminate by evidence all possible reasons for the making of the disposition other than an intention to prefer. This is so because the court, in drawing inferences from the proved facts, acts on a preponderance of probability. The inference of an intention to prefer is one which is, on a balance of probabilities, the most probable, although not necessarily the only inference to be drawn. If the facts permit of more than one inference, the court must select the most plausible or probable inference. If this favours the litigant on whom the onus rests he is entitled to judgment. If on the other hand an inference in favour of both parties is equally possible, the litigant will have not discharged the onus of proof [17](Own emphasis)

[47]Evidence presented before me in respect of charge 2 clearly indicates that the respondent reacted to the grievance that the respondent had lodged whereby she was exercising her rights, and most importantly the evidence of Mr Kruger as conceded that the decision to call the applicant before a disciplinary hearing and what led to her dismissal was the outcome of the grievance hearing. As I have mentioned that the outcome therein suggests nothing and/or raises the allegations in charge 2.

Grievance

JR1078/14

Bakker v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (JR1078/14) [2018] ZALCJHB 13 (24 January 2018)

Wulfsohn Motors (Pty) Ltd t/a Lionel Motors v Dispute Resolution Centre & Others (2008) 29 ILJ 356 (LC) at para [12]

Where it appears from the circumstances of a particular case that an employee could or should reasonably have channelled the dispute or cause of unhappiness through the grievance channels available in the workplace one would generally expect an employee to do so. Where however, it appears that objectively speaking such channels are ineffective or that the employer is so prejudiced against the employee that it would be futile to use these channels, then it may well be concluded that it was not a reasonable option in the circumstances.

[57]Absa took all reasonable steps to address the Applicants cause of complaints despite the fact that there was no substance to the complaints.

Change: consultation

JA90/15

Lou-Anndree v Afrox Oxygen Limited (JA90/15) [2018] ZALAC 4 (29 January 2018)

restraint of trade

JA48/2016

Labournet (Pty) Ltd v Jankielsohn and Another (JA48/2016) [2017] ZALAC 7; [2017] 5 BLLR 466 (LAC); (2017) 38 ILJ 1302 (LAC) (10 January 2017)

Court also finding that true dispute about retraining employee working for a competitor court restating that employee cannot be interdicted or restrained from taking away his or her experience, skills or knowledge, even if those were acquired as a result of the training which the employer provided to the employee. Labour Courts judgment upheld and appeal dismissed.

Reddy v Siemens Telecommunications (Pty) Ltd (above) is really covered by the relationship between the first and third questions identified in Basson v Chilwan (above) and relates to proportionality. See further Ball v Bambalela Bolts (Pty) Ltd and Another (above) at para 18.

the following questions require investigation,[9] namely, whether the party who seeks to restrain has a protectable interest, and whether it is being prejudiced by the party sought to be restrained. Further, if there is such an interest to determine how that interest weighs up, qualitatively and quantitatively, against the interest of the other party to be economically active and productive. Fourthly, to ascertain whether there are any other public policy considerations which require that the restraint be enforced. If the interest of the party to be restrained outweighs the interest of the restrainer the restraint is unreasonable and unenforceable.[10]

that the reasonableness and enforceability of a restraint depend on the nature of the activity sought to be restrained, the rationale (purpose) for the restraint, the duration of the restraint, the area of the restraint, as well as the parties respective bargaining positions. The reasonableness of the restraint is determined with reference to the circumstances at the time the restraint is sought to be enforced.[12] With reference particularly to the facts of this matter, it is an established principle of law that the employee cannot be interdicted or restrained from taking away his or her experience, skills or knowledge, even if those were acquired as a result of the training which the employer provided to the employee.[13]

[44] Even though it is acknowledged that it is difficult to distinguish between the employees use of his or her own knowledge, skill and experience, and the use of his or her employers trade secrets, it is accepted that an employee cannot be prevented from using what is in his, or her, head.[14]

Sibex Engineering Services (Pty) Ltd v Van Wyk and Another 1991 (2) SA 482 (T) at 507D-H.

In seeking to protect his investment in training the workmen, the employer is pursuing an objective which is unreasonable and contrary to public policy. For public policy requires that workmen should be free to compete fairly in the market place to sell their skills and know-how to their own best advantage; and the enforcement of a restraint which has no objective other than to stifle such free and fair competition is unreasonable and contrary to public policy.

Deductions: Section 34 of the BCEA

J1034/16

Maboza v Matjhabeng Local Municipality and Another (J1034/16) [2017] ZALCJHB 427 (23 November 2017)

[2] The deductions made by the First Respondent from the Applicants monthly remuneration to recover overpayments made as a result of her being paid as an Electrician at level 8 instead of level 9 (the overpayments) are unlawful by virtue of being in breach of s 34 of the BCEA.

[12] The deductions made must satisfy the requirements of s 34(1) to be lawful. If no agreement to the deduction is concluded in accordance with s 34(1)(a) then there must be some other source for the legal authority to make it in terms of s 34(1)(b), which inter alia authorises a deduction permitted in terms of a law. Section 34(5) is a provision in terms of the same Act, which permits deductions to be made for overpayments, but only if the reason for the overpayment was an error in calculating the employees remuneration. The error in this case was not one of calculation but one relating to the true level on which the applicant had been employed, so the employer cannot rely on s 34(5)(a).

Sibeko v CCMA (2001) JOL 8001 (LC)

It is indeed so that in terms of the Basic Conditions of Employment Act, an employer may not deduct amounts from the salary or remuneration of an employee without the employee's consent. Where an employee was however overpaid in error, the employer is entitled to adjust the income so as to reflect what was agreed upon between the parties in the contract of employment, without the employee's consent.' [4]

Jonker v Wireless Payment Systems CC (2010) 31 ILJ 381 (LC)

[21] In support of her case that her right had been interfered with the applicant relied on the provisions of s 34(1) of the Basic Conditions of Employment Act. That section prohibits an employer from making any deductions from an employee's remuneration unless the employee agrees in writing. It is indeed correct that as a general rule the Basic Conditions Employment Act prohibits deductions from employees' salaries without their prior consent. However, deductions without consent are permitted where they are permitted by the law, a collective bargaining agreement and a court order or arbitration award. In these instances all that the employer needs to do is to advise the employee of the error in payment and the deduction made or to be made. See Papier & others v Minister of Safety & Security & others (2004) 25 ILJ 2229 (LC).

Section Overpayment: s 34(5) of the BCEA

J1862/1

Sekhute and Others v Ekhuruleni Housing Company Soc (J1862/17) [2017] ZALCJHB 318 (5 September 2017)

15]I believe the trend discernible from the judgments cited is that repayment of overpaid remuneration is asui generiscategory of money lawfully recoverable by an employer from an employee and, on the same reasoning as that in theBoffard, is a way of recovering undue remuneration. At the very least, I believes 34(5)was clearly intended to authorise a particular type of deduction for amounts due to an employer not arising from debts of the kind contemplated bys 34(1)and even ifs 34(5)must be read as subject tos 34(1), thens 34(5)is a provision of a law contemplated ins 34(1)(b) which permits recovery without consent. At common law, the obligation of an employee to refund an employer for an overpayment made in error in essence would appear to be an obligation that could found an action based on unjust enrichment in the form ofthecondictio indebiti.[7]It would serve little purpose ifs 34(5)was included simply to reaffirm the existence of a common law right to recover payments made in error. The more plausible interpretation of the provision is that the legislature intended it to specifically authorise deductions for overpayments of remuneration.

SA Medical Association on behalf of Boffard v Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital & others (2014) 35 ILJ 1998 (LC)

[39] It is apparent from these decisions that the view taken by the Labour Court is that an overpayment as a result of an administrative error does not constitute remuneration as defined in terms of the BCEA. Since it is outside the parameters of the BCEA, an employer is not required to obtain the consent of an employee before effecting the deductions as required by s 34(1) of the BCEA.

Padayachee v Interpak Books (Pty) Ltd (2014) 35 ILJ 1991 (LC)

[27] It is noteworthy that the drafters of s 34 chose to identify and deal separately with a number of different types of deductions. This must mean that the purpose of the provision is to regulate these deductions.[28] It thus follows that any enquiry into s 34 should commence by identifying the nature and purpose of the deduction in dispute and then ascertain whether the section requires employers to regulate such deductions in a particular manner.[4]

probation

JR512/15

Bokwa Attorneys v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (JR512/15) [2017] ZALCJHB 344 (19 September 2017)

poor work performance

Palace Engineering (Pty) Ltd v Thulani Ngcobo and Others [2014] 6 BLLR 557 (LAC).

The acceptance of less compelling reasons for dismissal in respect of a probationary employee as contemplated in item 8(1)(j) of the Code does not, in my view, detract from the trite principle that the dismissal must be for a fair reason. Even though less onerous reasons can be accepted for dismissing a probationary employee, the fairness of such reasons still needs to be tested against the stipulations of item 8(1)(a)-(h) of the Code of Good Practice. At the end of the day, the onus rested on the employer to prove that the dismissal was substantively fair. The conspectus of the evidence proved the opposite, that the dismissal was substantively unfair.

[18] In his analysis, the arbitrator arrived at the finding that the applicant was not made aware of her non-performance after taking into consideration the third respondents undisputed evidence that she had no knowledge of her alleged under-performance, as her performance was not evaluated. In fact, it is apparent that the applicant did not clearly set out the third respondents performance standard except its expectation of her to perform independently. If the applicant did, the third respondent did not know her performance targets and her performance was clearly not assessed. It was further apparent that, if there was any performance standard or target, there was no evidence on the seriousness of the third respondents failure to meet such performance standard.

restraints of trade

J2832/16

Weir Minerals Africa (Pty) Ltd v Potgieter and Others (J2832/16) [2017] ZALCJHB 199 (26 May 2017)

[9] The principles relevant to the enforcement of restraints of trade are well- established and I do not intend to repeat them here. A party seeking to enforce the restraint agreement is required only to invoke the agreement and prove a breach of it. A respondent who seeks to avoid the restraint there has an onus to demonstrate on a balance of probabilities that the restraint agreement is unenforceable because it is unreasonable.

Basson v Chilwan and others [1993] ZASCA 61; 1993 (3) SA 742 (A)

where the court stated that the reasonableness or otherwise of a restraint is to be determined by the following: 1. Is there an interest of the one party, which is deserving of protection at the termination of the agreement? 2. Is that interest being prejudiced by the other party? 3. If so, does the interest weigh up qualitatively and quantitatively against the interests of the latter party so that the latter should not be economically inactive or unproductive? 4. Is there another facet of public policy having nothing to do with the relationship between the parties but which requires that the restraint should either be maintained or rejected?

[10] It is equally well-established that in relation to the first enquiry established byBasson v Chilwanthat proprietary interests deserving of protection are of two kinds. The first is all confidential matter which is useful for the carrying on of the business and which could be used by competitor, if disclosed to them, to gain a relative competitive advantage. The second is the relationships with customers, potential customers, suppliers and others that go to make up what is referred to as the trade connections of the business. The onus is on the respondent to prove the unreasonableness of the restraint.

New Just Fun Group (Pty) Ltd v Turner and others(J786/14, unreported)

The truncated relief sought seeks to limit the scope of the restraint There are at least two reasons why the applicant ought not to be bound to attempt to enforce the full ambit of the restraint. First, it is well-established that a court is entitled to enforce the restraint partially by restricting the scope of its operation to reflect what is found to be reasonable.

fixed term: reasonable expectation

JR322/15

Rademeyer v Aveng Mining Ltd and Others (JR322/15) [2017] ZALCJHB 257 (28 June 2017)

Section 186(1)(b)

De Milander v Member of the Executive Council for the Department of Finance: Eastern Cape and Others (2013) 34 ILJ 1427 (LAC)

The test whether or not an employee has discharged the onus is objective, namely, whether a reasonable employee would, in the circumstances prevailing at the time, have expected the employer to renew his or her fixed-term contract on the same or similar conditions.... In order to assess the correctness of Mr Le Roux's contention that the appellant had a reasonable expectation that her contract would be renewed and that the MEC's failure to renew it constituted a dismissal, it is first necessary to determine whether she in fact expected her contract to be renewed, which is the subjective element. Secondly, if she did have such an expectation, whether taking into account all the facts, that expectation was reasonable, which is the objective element. Whether or not her expectation was reasonable will depend on whether it was actually and genuinely entertained

payment of performance bonus

JS845/2014

Country Thorp v National Homebuilders Registration Council (JS845/2014) [2017] ZALCJHB 167 (6 April 2017)

Claim in contract for payment of performance bonus and golden handshake. On the facts - bonus payment discretionary, and cannot form basis of claim in contract, plaintiff failed to prove agreement in terms of which he would be paid a lump sum at termination of fixed term contract in the event of non-renewal.

Deductions: Section 34 of the BCEA, procedure

JS708/14

Mpanza and Another v Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development and Correctional Services and Others (JS708/14) [2017] ZALCJHB 48; (2017) 38 ILJ 1675 (LC); [2017] 10 BLLR 1062 (LC) (31 January 2017)

In terms of section 34 (2) (b) of the BCEA the respondents had to follow a fair procedure and had to give the applicants a reasonable opportunity to show why the deductions should not be made. The applicants were given letters by Ms Phahlane who asked them to give reasons why the deductions were not to be made. They received the letters. Their testimony was that they responded to the letters. They were asked to produce proof of their submission of their responses but none was forthcoming. The probability is that the applicants failed to tender their responses.

failure of an employer to comply with its disciplinary procedure

J2819/16

Motale v The Citizen 1978 (Pty) Ltd and Others (J2819/16) [2017] ZALCJHB 22; [2017] 5 BLLR 511 (LC) (27 January 2017)

[28]. There are number of judgments dealing with the failure of an employer to comply with its disciplinary procedure, specifically when the disciplinary procedures form part of the contract of employment

Ngubeni v The National Youth Development Agency and Another (2014) 35 ILJ 1356 (LC); and Solidarity and Others v South African Broadcasting Corporation 2016 (6) SA 73 (LC); (2016) 37 ILJ 2888 (LC).

the Court held that failure of an employer to comply with its disciplinary code procedure, where the disciplinary code procedure forms part of employees contract is a breach of that contract entitling the employee to relief. In both matters the court declared the decision by the employer to terminate the contract without complying with the disciplinary code to a breach of contract entitling the employees to be reinstated.

[29]. The applicants contract of employment specifically incorporates the disciplinary code and procedure and it is clear that the respondents had not complied with the disciplinary code and procedure when they terminated the applicants contract. As a result, I am satisfied that the respondents termination of the applicants contract of employment constituted a breach thereof and that the applicant is entitled to be reinstated.

[30]. Given the specific circumstances of this matter and in particular the applicants complaint regarding the failure of the respondents to conduct a disciplinary inquiry and the position he found himself in at the time of termination of his contract it is appropriate that his reinstatement be accompanied by an order directing the respondents comply with the disciplinary code and procedure, in other words in order for specific performance.

[32]. There is no reason why despite the absence of urgency and the limited relief that the applicant is entitled to that cost should not follow the result.

Signing of contract

Employer claiming that it had made a reasonable error in not reading the pro forma contract. The failure to check the contract also had to be seen in the context of a prior understanding. Given this context there was a duty on the applicant to mention the material amendments and the doctrine of caveat subscriptor could not assist him.

Salary deduction

Salary deductions, not entitled to rely on s 34(1)(b) and ignore s 34(1)(a) and 34(2). Purpose of provision and formalities clearly to protect employees against arbitrary conduct and to provide employers with simple and quick method of obtaining relief without resorting to litigation.

Remuneration. Leave pay. Contrary to provisions of the BCEA that an employee entitled to accumulate leave pay for more than one leave cycle.

Jardine v Tongaat-Hulett Sugar Ltd [2003] at 7 BLLR 717 (LC) which had held that leave not taken within the six months after the end of a leave cycle was not automatically forfeited nor was any rights to payment in respect of that leave forfeited.

Jooste v Kohler Packaging Ltd (2004) 25 ILJ 121 (LC) where the court held that the pro-rated payment in respect of a current leave cycle aside, s 40 of the BCEA contemplated payment only in respect of leave immediately preceding that during which the termination took place.

Change of

the duties of the new manager was similar to the employees duties and that by taking away duties it amounted to taking away her responsibilities which resulted in the diminution of her status.

Transfer of employee

Minister had the power to transfer the employee in terms of s 14 of the Public Service Act and, as the executive authority, also had the power to direct the employee temporarily to perform other functions in terms of s 32 of that Act. She had suffered no reduction in salary and had not been demoted.

Restraint of trade

He refused to sign the restraint of trade agreement. Amounted to a fundamental change to the terms and conditions of his employment that were clearly less favourable. Dismissal was procedurally unfair and the applicant was to be paid an amount equal to 12 months.

Benefit, Travel allowance falling withinextended definition of benefit.

no longer provide transport to employees and that it would no longer allow employees to leave at midday on the last Friday, not conditions of employment: they were not provided for in any contract of employment or in thecollective agreement and they were nothing more than long-standing practices.

Transfer to new post, Impermissible to place employee in new postwithout meaningful consultation.

Benefit

S 186(2)(a) , employee, she would in accordance with Schoeman v Samsung not have the right tostrike. The notion that the benefit had to be based on an ex contractu or ex lege entitlementwould, in a case like the present, render the unfair labour practice jurisdiction sterile. Thebenefit in s 186(2)(a) of the Act meant existing advantages or privileges to which anemployee was entitled as a right or granted in terms of a policy or practice subject to theemployers discretion. In as far as Hospersa, GS4 Security and Scheepers postulated adifferent approach, they were wrong.

deductions from his salary, in contravention of s 23 of the BasicConditions of Employment Act 75 of 1997 which allowed a maximum of 25% of an employees remuneration to be deducted. Debt had prescribed three years after it became due, s 11(d) of the Prescription Act 68 of 1969.

J1926/12

POPCRU obo Moyo v Minister of Correctional Services and Another

excludes overtime

JA49/08

Mondi Packaging (Pty) Ltd v Director-General: Labour & Others

termination of service

subsequently attempting to change notice

showing no prima facie right

J905/10

De Villiers v Premier, Eastern Cape and Others

Employment contract

Unilateral change to individuals contract

employer could not unilaterally implement a change to terms and conditions of employment

Earnings threshold

not include overtime pay

BCEA

contractual terms

s 4, 70, 77(1) BCEA

Jurisdiction

No costs orders if value = small claims court

J2218/08

Fourie v Stanford Driving School and 34 related cases

due and enforceable; much less that it was liquidated in the sense that it was capable of speedy and easy proof

Severance pay

s 41 of the BCEA,

Set-off could not be equated to a prohibited deduction in terms of s 34 of the BCEA under those circumstances.

change the shift patterns, it was clear that they fell squarely within the definition of operational requirements

unilateral change to terms and conditions of employment

determination of their shift patterns remained within the applicants prerogative as a work practice

s 77(3) BCEA

ordered to restore and comply with the terms

change working hours

only through collective agreement

Breach of contract; claim for damages

7 days notice- short notice.

employer as such had failed to show that the alleged loss

Deductions benefit

BCEA applies where no Collective agreement

unilaterally changed her conditions of employment.

National Union of Mineworkers v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (2007) 28 ILJ 1614 (LC)

An inference from circumstantial evidence could be drawn only if there existed objective facts from which to infer other facts which was sought to be established; did not apply to the situation where a party brought a claim that fell under the jurisdiction of the court, lost and then wanted to rely on an alternative claim that should have been referred to the CCMA or bargaining council

D352/06

Adcan Marine v CCMA & Others

Other case law cited

Chirwa v Transnet Ltd and Others (2008) 2 BLLR 97 (CC)

77(3) of the BCEA

could not be interpreted so widely as to include any matter concerning a contract of employment, which was already regulated in the LRA

Sick leave notice period

Change of vested rights

No, only work practices

No strike

Benefits

Transport allowance not wage increase

Public Holidays

Sunday was public holiday. It remained a public holiday, and that the Monday succeeding was added to the list of public holidays

Remuneration

NEMISA was in breach of the employment contract by not paying him for services duly tendered

Working hours

that operational requirements could not provide valid justification for effecting a reduction in working hours without the agreement of all parties. Held further that without agreement being obtained this constituted a repudiation of their terms of employment and was unlawful

Leave payment

employer was not entitled to treat the employee as having forfeited his right to leave in excess of 40 days

the employer had a contractual obligation to pay the excess because in terms of the contract of employment it bore an obligation to ensure that the employee took leave as and when it became due and because it had dismissed the employee (for misconduct), thus depriving the employee of taking any leave prior to the termination of his contract

in respect of the accumulation of leave the provisions of the BCEA were more favorable to the employee than those in his contract of employment; It does not impose an obligation on the employee to take leave within six months after the end of the annual leave cycle. Leave not taken within six months is not automatically forfeited. Held further, however, that an employer can require an employee contractually to take leave in terms of s20(4) .

D849/02

Jardine v Tongaat-Hulett Sugar Ltd

only one time period in s64(1)(a), namely the period of 30 days mentioned in s64(1)(a)(ii). The LC held that the issuing of a certificate is not a reference to a time period but to the happening of an event, and concluded that it was competent to order the employer to refrain from implementing the change for 30 days from the date of referral of the dispute, notwithstanding that conciliation had taken place and a certificate of outcome issued.

where an employer takes away a company car from an employee, which car the employee is entitled to in terms of the contract of employment, that act constitutes a repudiation of the employment contract and therefore a dispute of right. Held that the dispute in casu manifestly related to training and the employees conditions of service and was a dispute of right. Held further: There can be no doubt that, where there is a dispute of right that relates to training, it is possible to have conduct by an employer that can be described as unfair conduct or as an unfair labour practice as contemplated by item 2(1)(b). Such a dispute would be arbitrable in terms of item 3(4) of schedule 7 and the CCMA would have jurisdiction to arbitrate it if there was no council with jurisdiction to arbitrate it.

Unilateral change

Retrenchment

If the reason for a dismissal is to compel employees to accept a demand in respect of a matter of mutual interest between the employer and employees, such a dismissal is deemed to be automatically unfair [32] Having regard to the facts, and the circumstances, of this case, it appears that the [employer] dismissed the unions 58 members for the reason that it wanted to compel them to accept its demand for a reduction in wage levels. In the Courts view, the [employer] fell foul of s187(1)(c) of the [LRA]. Held that the employer had used outsourcing as a device, for undermining the status of the union as the exclusive recognised collective bargaining agent of its members, the dismissed employees. Concluded that the dismissal of the employees was automatically unfair

Case law sited

SA Democratic Teachers Union v Minister of Education & others (2001) 22 ILJ 2325 (LC) and referring to ECCAWUSA & others v Shoprite Checkers t/a OK Krugersdorp (2000) 21 ILJ 1347 (LC),

Change

Such changes are justified if they are made in the course of a bona fide retrenchment exercise and as an alternative to retrenchment

had been dismissed for refusing to accept the change to his terms and conditions of employment and that his dismissal was automatically unfair

free transport

were told would be provided

Agreement

Settlement: section 158(1A) of the LRA.

J846/2017

Imatu obo Nathan v Polokwane Local Municipality (J846/2017) [2019] ZALCJHB 290; (2020) 41 ILJ 937 (LC) (18 October 2019)

[77] As emphasised in Fleet Africa, section 158(1A) does not require that a dispute should have been referred to a council/the CCMA or the Labour Court.

[75] In the circumstances, the agreement reached on 24 January 2017 complied with the common law requirements of a valid contract, and I now turn to the statutory requirements to make a settlement agreement an order of this Court.

[53] Section 158(1)(c) of the LRA provides that this Court may make a settlement agreement an order of court if certain requirements are met. These requirements are set out in section 158(1A), namely, there should be a) a written agreement, b) in settlement of a dispute, c) that a party has the right to refer to arbitration or to the Labour Court, but d) excluding disputes contemplated in sections 22(4), 74(4) or 75(7) of the LRA. Sections 22(4), 74(4) and 75(7) of the LRA deal with organizational rights disputes, disputes in essential services, and disputes in maintenance services respectively. The applicants dispute does not concern any of these categories of dispute.

Fleet Africa (Pty) Ltd v Nijs (2017) 38 1059 (LAC) at para 20.

Fleet Africa referred with approval to its decision in Universal Church of the Kingdom of God v Myeni and Others (2015) 36 ILJ 2832 (LAC) at para 44.

It is settled law that the intention of the parties in any agreement express or tacit is determined from the language used by the parties in the agreement or from their conduct in relation thereto. Further, not every agreement constitutes a contract. For a valid contract to exist, each party needs to have a serious and deliberate intention to contract or to be legally bound by the agreement, the animus contrahendi. The parties must also be ad idem (or have a meeting of minds) as to the terms of the agreement. Obviously, absent the animus contrahendi between the parties or from either of them, no contractual obligations can be said to exist and be capable of legal enforcement.

[56] The statutory requirements are that the agreement a) must be in writing, b) must settle a dispute and c) this dispute must be one which a party has the right to refer to arbitration or the Labour Court (excluding organizational rights, essential services and maintenance services disputes). The requirement is not that the dispute has been referred to arbitration or the Labour Court simply that the nature of the dispute is one which a party could refer to arbitration or to the Labour Court.

De Wet & Van Wyk Kontraktereg & Handelsreg Vyfde Uitgawe, p170.

[73] A repudiation does not dissolve the contract. It grants the innocent party two options, namely to either accept the breach and sue for damages, or to hold the repudiator to the contract. If the innocent party rejects the repudiation and holds the repudiator to the contract, the contract and the obligations created by it remain intact.

Turquand rule: Ostensible authority

JA112/2013

City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality and Others v Independent Municipal and Allied Trade Union and Others (JA112/2013) [2017] ZALAC 43; (2017) 38 ILJ 2695 (LAC) (28 June 2017)

This is a principle that was developed in Royal British Bank v Turquand [1856] EngR 470; (1856) 6 E & B 327; 1843-60 ALL ER 435, which provides that persons contracting with a company and dealing in good faith may assume that acts within its constitution and powers have been properly and duly performed and are not bound to enquire whether acts of internal management had been regular- per Lord Simons in Morris v Kanssen 1946 AC 459 at 474; (1946) 1 ALL ER 586 (HL) at 592 approving the formulation of the rule in Halsburys Laws of England 2ed vol 5 432 para 698.

See NBS Bank Ltd v Cape Produce Co (Pty) Ltd and Others 2002 (1) SA 396 (SCA) para 2; Northern Metropolitan Local Council v Company Unique Finance (Pty) Ltd and Others 2012 (5) SA 323 (SCA) para 28.

ostensible authority to bind SALGA in concluding the settlement agreement it was incumbent upon IMATU to prove the following: (a) a representation in words of conduct; (b) made by SALGA that either, or any, or all of those persons had the authority in respect of the settlement, to act as they, respectively, or jointly, did; (c) a representation in a form such that SALGA should have reasonably expected that outsiders would act on the strength of it; (d) reliance by IMATU on such representation; (e) the reasonableness of such reliance; and (f) the consequent prejudice to IMATU.

[71] ...the Turquand rule finds no application.[20] The rule does not entitle a third party to assume that SALGA has in fact entered into the settlement agreement. The respondents did not show that Messrs Dlamini and/or Van Zyl had actual authority in terms of SALGAs constitution to enter into the settlement agreement.

JR249/2015

A C and C South Africa (Pty) Ltd t/a African Camp and Catering v Nkadimeng NO and Others (JR249/2015) [2017] ZALCJHB 283 (8 August 2017)

Universal Church of the Kingdom of God v Myeni and Others (2015) 36 ILJ 2832 (LAC); [2015] 9 BLLR 918 (LAC); [2015] JOL 33521 (LAC); at para 44

It is settled law that the intention of the parties in any agreement - express or tacit - is determined from the language used by the parties in the agreement or from their conduct in relation thereto. Further, that not every agreement constitutes a contract. For a valid contract to exist, each party needs to have a serious and deliberate intention to contract or to be legally bound by the agreement, theanimus contrahendi. The parties must also be ad idem (or have the meeting of the minds) as to the terms of the agreement. Obviously, absent theanimus contrahendibetween the parties or from either of them, no contractual obligations can be said to exist and be capable of legal enforcement.

Settlement

JS644/15

Food and Allied Workers Union and Others v Amalgated Beverage Industries (Pty) Ltd (JS644/15) [2017] ZALCJHB 492 (20 April 2017)

unreasonably refusing with prejudice settlement offer equivalent to maximum compensation...applicants therefore not entitled to costs

include grounds ito section 145

NOT

PA10/09

Volkswagen v Koorts