par Peace Umutoni Il y a 2 années

102

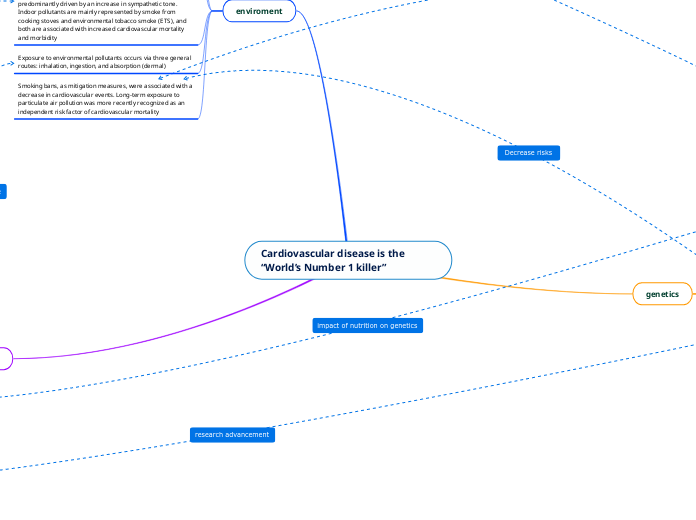

Cardiovascular disease is the “World’s Number 1 killer”

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death globally, with various lifestyle and environmental factors contributing to its prevalence. Prolonged screen time and sedentary behaviors starting in adolescence have been linked to increased cardiovascular risk in adulthood.