Introducing Interpreting Studies

Add the name of the author.

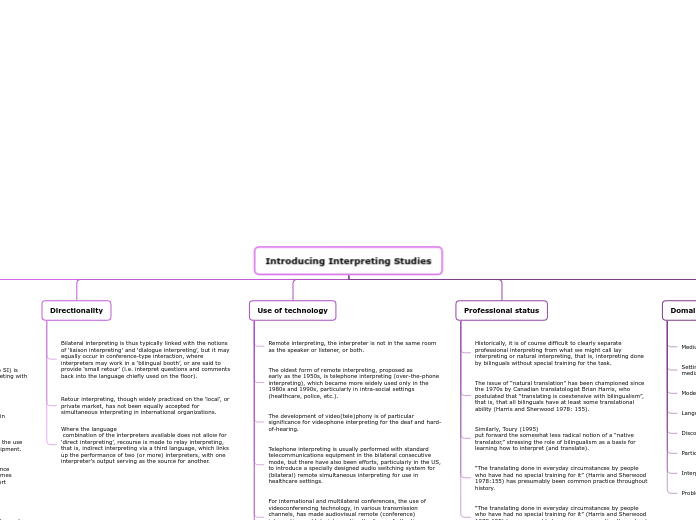

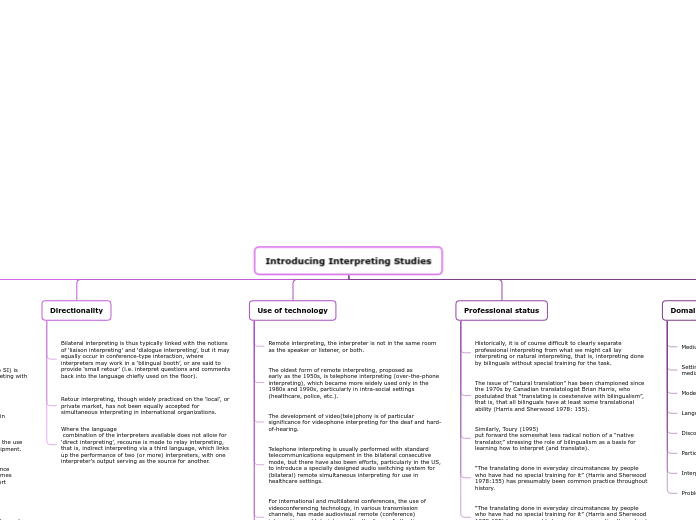

Domains and dimensions

Add their major accomplishments, honors, prizes, titles that the author won.

Problem simultaneity, memory, quality, stress, effect, role

Interpreter prof. trained, semi prof., natural

Participants equal representatives

Discourse speeches, debates, face to face talk

Languages spoken, conf. lang., migrant lang.

Mode consecutive, simultaneous, booth, whispering - sight

Setting international, intra-social,multilat. conf., int. organ. media, courts, police, health/social

Medium human-machine

Professional status

You can add here people, places or events that took part in the author's character formation.

“The translating done in everyday circumstances by people who have had no special training for it” (Harris and Sherwood 1978:155) has presumably been common practice throughout history.

Similarly, Toury (1995)

put forward the somewhat less radical notion of a “native translator,” stressing the role of bilingualism as a basis for learning how to interpret (and translate).

The issue of “natural translation” has been championed since the 1970s by Canadian translatologist Brian Harris, who postulated that “translating is coextensive with bilingualism”, that is, that all bilinguals have at least some translational ability (Harris and Sherwood 1978: 155).

Historically, it is of course difficult to clearly separate

professional interpreting from what we might call lay interpreting or natural interpreting, that is, interpreting done by bilinguals without special training for the task.

Use of technology

Add the author's dislikes.

Machine interpreting should be within the interpreting scholar’s purview, the prospects for ‘fully automatic high-quality interpreting’ remain doubtful at best.

No less future-oriented than technology-driven forms of remote interpreting (which, despite complaints about the ‘dehumanization’ of interpreting, continue to rely on specially skilled human beings) are attempts at developing automatic

interpreting systems on the basis of machine translation software and technologies for speech recognition and synthesis.

For international and multilateral conferences, the use of videoconferencing technology, in various transmission channels, has made audiovisual remote (conference) interpreting and tele-interpreting the focus of attention,

and this area can be expected to remain among the most dynamically evolving domains of interpreting in the future.

Telephone interpreting is usually performed with standard

telecommunications equipment in the bilateral consecutive mode, but there have also been efforts, particularly in the US, to introduce a specially designed audio switching system for (bilateral) remote simultaneous interpreting for use in healthcare settings.

The development of video(tele)phony is of particular significance for videophone interpreting for the deaf and hard-of-hearing.

The oldest form of remote interpreting, proposed as

early as the 1950s, is telephone interpreting (over-the-phone interpreting), which became more widely used only in the 1980s and 1990s, particularly in intra-social settings (healthcare, police, etc.).

Remote interpreting, the interpreter is not in the same room as the speaker or listener, or both.

Directionality

Add the author's likes: this category is wide, you can mention their hobbies, food preference, any other likes. etc.

Where the language

combination of the interpreters available does not allow for ‘direct interpreting’, recourse is made to relay interpreting, that is, indirect interpreting via a third language, which links up the performance of two (or more) interpreters, with one

interpreter’s output serving as the source for another.

Retour interpreting, though widely practiced on the ‘local’, or private market, has not been equally accepted for simultaneous interpreting in international organizations.

Bilateral interpreting is thus typically linked with the notions

of ‘liaison interpreting’ and ‘dialogue interpreting’, but it may equally occur in conference-type interaction, where interpreters may work in a ‘bilingual booth’, or are said to provide ‘small retour’ (i.e. interpret questions and comments back into the language chiefly used on the floor).

Working mode

You can add further details regarding the author's work, like which publishing house they are/were working for. You can add their publications too.

In text-to-sign interpreting, the interpreter may need to alternate between reception (reading) and production (signing), thus bringing sight translation closer to the (short) consecutive mode.

‘Sight translation’, this variant of the simultaneous mode, when practiced in real time for immediate use by an audience, would thus be labeled more correctly as ‘sight interpreting’.

Whereas the absence of acoustic source–target overlap makes simultaneous interpreting (without audio transmission equipment) the working mode of choice for sign language interpreters. Only where the interpreter works right next to one or no more than a couple of listeners can he or she provide a rendition by whispered interpreting.

Note-taking as developed by the pioneers of conference interpreting in the early twentieth century. Is sometimes referred to as ‘classic’ consecutive, in contrast to short

consecutive without notes, which usually implies a bidirectional mode in a liaison

constellation.

Consecutive simultaneous, has become feasible with the use of highly portable digital recording and playback equipment.

Simultaneous consecutive the simultaneous

transmission of two or more consecutive renditions in different output languages.

Simultaneous interpreting (frequently abbreviated to SI) is often used as shorthand for ‘spokenlanguage interpreting with the use of simultaneous interpreting equipment in a

sound-proof booth’.

Consecutive interpreting (after the source-language

utterance)