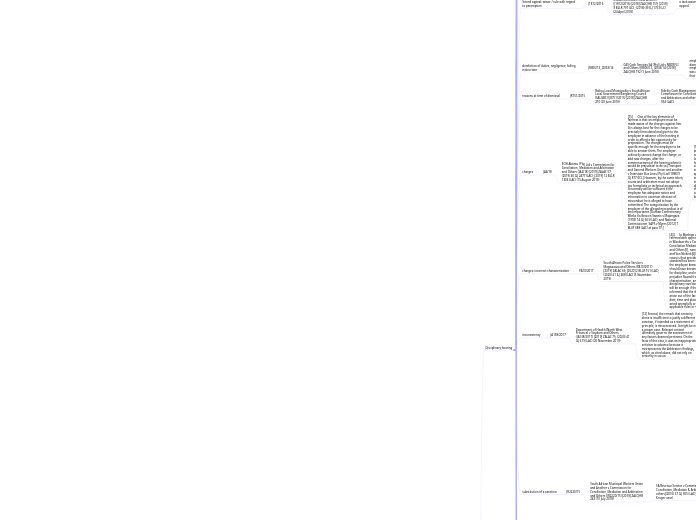

Labour Law cases decided in the South African Courts (Highlights and updated 1997 to December 2022 [Copyright: Marius Scheepers/10.3.1])

Disciplinary hearing, Suspension.

precautionary suspension

JS316/18

NEHAWU obo Coetzee and Others v Kakamas Water Users Association (JS316/18) [2021] ZALCJHB 447 (8 December 2021)

[127] Section 186(2)(b) of the LRA defines an unfair labour practice as any unfair act or omission that arises between an employer and employee involving inter alia the unfair suspension of an employee. In my view, an employer would invite an unfair labour practice dispute relating to suspension if an employee is suspended pending a disciplinary hearing if there is no justification to suspend such employee.

precautionary and punitive suspensions: The narrow issue before this Court is whether the Applicant's decision to suspend the Third Respondent without pay constituted an unfair labour practice in terms of section 186(2)(b) of the LRA.

JR2507/15

American Products Services (Pty) Ltd v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (JR2507/15) [2020] ZALCJHB 113 (15 July 2020)

Referencing the decision of this Court in Koka v Director-General: Provincial Administration North West Government,[[1997] 7 BLLR 874 (LC)] the Second Respondent distinguished between two types of suspension. The first type of suspension, so the Second Respondent reasoned, was a "holding operation" where the suspension is not designed to impose discipline but is rather for reasons of good administration. The second type of suspension serves as a form of disciplinary action.The Second Respondent held that "the first form of suspension applies to the Applicant because the Respondent suspended him pending an investigation into the circumstances of the accident involving the Respondent's truck in which the Applicant was driving".[]Further to this, the Second Respondent noted that precedent exists in Sappi Forests (Pty) Ltd v CCMA and Others[[2009] 3 BLLR 254 (LC)] that "it is normally unlawful and unfair to suspend an employee without pay pending a disciplinary enquiry".[6] It was common cause that the Third Respondent had been suspended without pay, and that he had not agreed to this form of suspension. For this reason, the suspension was found to be substantively unfair.

As noted by Grogan in Workplace Law, while the wording of section 145 of the LRA appears to refer to suspensions only when imposed as a disciplinary sanction, it is now settled that both precautionary and punitive suspensions fall within the terms of section 186(2)(b) of the LRA.[18] The dicta of Murphy AJA in Member of the Executive Council for Education, North West Provincial Government v Gradwell[(2012) 33 ILJ 2033 (LAC) at para 44.] is an appropriate starting point, where the learned judge stated that:"Ultimately, procedural fairness depends in each case upon the weighing and balancing of a range of factors including the nature of the decision, the rights, interests and expectations affected by it, the circumstances in which it is made, and the consequences resulting from it. When dealing with a holding operation suspension, as opposed to a suspension as a disciplinary sanction, the right to a hearing, or more accurately the standard of procedural fairness, may legitimately be attenuated, for three principal reasons. Firstly, as in the present case, precautionary suspensions tend to be on full pay with the consequence that the prejudice flowing from the action is significantly contained and minimized. Secondly, the period of suspension often will be (or at least should be) for a limited duration ... And, thirdly, the purpose of the suspension - the protection of the integrity of the investigation into the alleged misconduct - risks being undermined by a requirement of an in-depth preliminary investigation".

Further to this, the principles for a fair 'preventive' suspension were outlined in Mogothle v Premier of the Northwest Province[(2009) 30 ILJ 605 (LC) at para 39.] as follows:"[T]he application of the contractual principle of fair dealing between employer and employee . . . requires first that the employer has a justifiable reason to believe, prima facie at least, that the employee has engaged in serious misconduct; secondly, that there is some objectively justifiable reason to deny the employee access to the workplace based on the integrity of any pending investigation into the alleged misconduct or some other relevant factor that would place the investigation or the interests of affected parties in jeopardy; and thirdly, that the employee is given the opportunity to state a case before the employer makes any final decision to suspend the employee".

This notion was embellished by the Court in Harley v Bacarac Trading 39 (Pty) Ltd[(2009) 30 ILJ 2085 (LC) at para 31.] where the unlawfulness of a "holding operation" suspension was linked to a breach of material terms of a contract of employment:"Suspension without pay and the fairness thereof, are self-evidently linked to the payment of remuneration, especially where, as is the case here, an employee is suspended without pay. Where suspension is effected as a measure pending a disciplinary hearing, as is the case here, suspension without pay is a material breach of contract. In the absence of any apparent apprehension that the applicant's continued B presence in the workplace prejudiced a legitimate business interest and in view of the demonstrated psychological and financial prejudice to the applicant, the applicant's suspension was also unfair".

As held by the Constitutional Court in Long v South African Breweries (Pty) Ltd,[(2019) 40 ILJ 965 (CC) at para 24.] it is settled that "where the suspension is precautionary and not punitive, there is no requirement to afford the employee an opportunity to make representations".[26] With this said, I am not of the opinion that this creates a blanket exemption from affording employees with an opportunity to make representations. The Court in Long however went on to assess that based on the facts before it:"The finding that the suspension was for a fair reason, namely for an investigation to take place, cannot be faulted. Generally, where the suspension is on full pay, cognisable prejudice will be ameliorated. The Labour Courts finding that the suspension was precautionary and did not materially prejudice the applicant, even if there was no opportunity for pre-suspension representations, is sound".[27]

The facts before this Court are distinguishable. The prejudice caused to the Third Respondent by Applicant have rather been exacerbated by the Applicant's decision to suspend him without pay. There is nothing to motivate the failure to provide the Third Respondent with an opportunity to make representations regarding his suspension. I am of the firm view that given the punitive nature of the suspension, a hearing ought to have been conducted prior to the action being taken. This would not have been the case were the suspension to have been with pay.

Resolution: employer not complying with its own rules

J1485/2019

Gallocher v Social Housing Regulatory Authority and Another (J1485/2019) [2019] ZALCJHB 162; (2019) 40 ILJ 2723 (LC) (3 July 2019)

Manamela Ida v Department of Co-Operative Governance, Human settlements and Traditional Affairs Limpopo Province and Another (J1886/2013) [2013] ZALCJHB 225 (5 September 2013) at para 20. See also Matola (supra) at para 28; Biyase v Sisonke District Municipality and Another (2012) 33 ILJ 598 (LC) at para 20; Lebu v Maquassi Hills Local Municipality and Others (2) (2012) 33 ILJ 653 (LC) at para 17.

A suspension would be unlawful in instances where the right or power of an employer to effect a suspension is prescribed by specific regulation and these regulations are not complied with by the employer. The unlawfulness is founded in the employer not complying with its own rules. the issue of the lawfulness of the suspension must be based solely on the provisions of the regulatory provisions themselves, as defined therein, and thus only concern the interpretation and application of the actual regulatory provisions in order to assess and determine compliance by the employer.

Mbatha v Ehlanzeni District Municipality and Others (2008) 29 ILJ 1029 (LC)

My considered opinion is that the power to discipline the municipal manager must reside exclusively in the council. I conclude therefore that this power to discipline a municipal manager is vested in the council alone and is not capable of being delegated to an executive mayor. The purported delegation of disciplinary powers of the council was consequently unlawful for want of legality.

[2018] ZACC 7 at paras 23 -25.

Long v South African Breweries (Pty) Ltd and Others

In respect of the merits, the Labour Courts finding that an employer is not required to give an employee an opportunity to make representations prior to a precautionary suspension, cannot be faulted. As the Labour Court correctly stated, the suspension imposed on the applicant was a precautionary measure, not a disciplinary one. This is supported by Mogale, Mashego and Gradwell. Consequently, the requirements relating to fair disciplinary action under the LRA cannot find application. Where the suspension is precautionary and not punitive, there is no requirement to afford the employee an opportunity to make representations.In determining whether the precautionary suspension was permissible, the Labour Court reasoned that the fairness of the suspension is determined by assessing first, whether there is a fair reason for suspension and secondly, whether it prejudices the employee. The finding that the suspension was for a fair reason, namely for an investigation to take place, cannot be faulted. Generally where the suspension is on full pay, cognisable prejudice will be ameliorated. The Labour Courts finding that the suspension was precautionary and did not materially prejudice the applicant, even if there was no opportunity for pre-suspension representations, is sound. (Footnotes omitted)

Special leave

J4584/2018

Chanda v Ratlou Local Municipality (J4584/2018) [2018] ZALCJHB 428 (28 December 2018)

Heyneke v Umhlatuze Municipality (2010) 31 ILJ 2608 (LC) at para [33] [34]

Special leave that is imposed on employees is effectively a suspension in the hope of subverting the residual unfair labour practice provisions of the Labour Relations Act No. 66 of 1995 (LRA) and all the time and other constraints that accompany suspensions.To discharge its onus of proving the... lawfulness of the special leave the municipality has to show that the special leave was at all times at the instance of the employee and with his consent, that it was not imposed on him, that exceptional circumstances existed and that the special leave resolution was adopted in good faith, and that it was rational, reasonable, proportionate and in the public interest.

6.14 In this case, given the haste and manner with which the forced special leave was imposed on the Applicant, it is apparent that the Respondent sought to subvert the provisions of Local Government: Disciplinary Regulations for Senior Managers, and I am satisfied that the Applicant has established a clear right to the relief that he seeks, as no attempt was made to comply with the provisions of the Regulations in suspending him, and furthermore, there is no source document or authority relied upon by the Respondent in imposing the forced special leave.

J2903/16

Johannesburg Metropolitan Bus Service Soc Limited v DEMAWUSA and Others (J2903/16) [2017] ZALCJHB 1 (6 January 2017)

A trade unions authority to act on behalf of employees is limited to the powers granted to it inSection 200of theLabourRelations Act 66 of 1995. Absent proof of trade union membership, the trade union lacks the authority to act.

J2455/16

Hlehlethe v CEPWAWU (J2455/16) [2017] ZALCJHB 215 (5 June 2017)

Accordingly the applicant cannot rely on unfair conduct relating to the right to be heard prior to suspension, or other unfair conduct, in these proceedings. If the applicant wants to rely on the principle of unfairness and allege that he has been unfairly treated he can only do so in terms of the unfair labour practise jurisdiction and raise this issue in terms of unfair labour practise dispute resolution processes in the CCMA.

Koka v Director General Provincial Administration North West Government(1997) 18 ILJ 1718 (LC)

Lewis v Heffer and Others 1978 (3) All ER 354 (CA) at 364 C to E

Very often irregularities are disclosed in a government department or in a business house and a man may be suspended on full pay pending enquiries. Suspension may rest on him and he is suspended until he is cleared of it. No one as far as I know has ever questioned such a suspension on the ground that it could not be done unless he is given notice of the charge and an opportunity of defending himself and so forth.The suspension in such a case is merely done by way of good administration. A situation has arise in which something must be done at once. The work of the department or office is being affected by rumours and suspicions. The others will not trust the man. In order to get back to proper work the man is suspended. At that stage the rules of natural justice do not apply.

Madamela Ida v The Department of Corporate Governments 2014 ZALCJHB 225 dated 5 September 2013 at paragraph 17

At level of general principle precautionary suspension is a unilateral act by the employer which need not be preceded by the application of the principles of audi alteram partem.It is only where specific rules which is often the case in the public centre, in the public sector, prescribe the application of audi alteram partem prior to suspension that it must be applied. It is then applied not because of a general principle of the right to be heard but because the particular rule in fact stipulates it as an essential requirement. In that case the compliance is so because the employer has made its own rules and must comply with them.

Nyati v Special Investigating Unit (2011) 32 ILJ 2991 (LC), Biyase v Sisonke District Municipality and Another (2012) 33 ILJ 598 (LC), Lebo v Makwassi Hills Municipality and Another (2) (2012) 33 ILJ 653 (LC) and SAMWU on behalf of Dlamini and 2 Others v Mogale City Local Municipality and Another [2014] 12 BLLR 1236 (LC).

Relief

JS 929/14

Nwaogu v Bridgestone SA and Another (JS 929/14) [2016] ZALCJHB 104 (18 March 2016)

Dince and Others v MEC, Education North West (2010 21 ILJ 1193 (LC).

[23] The important principle enunciated in theMhlauliandMullercases is that the audi alteram partem rule applies in cases of suspension. It is also important to note that the court in theMhlaulicase held that the correct approach to adopt in cases of suspension was that enunciated in theMullercase and that those cases which held that the audi alteram rule does not apply were wrongly decided. I align myself with that approach and wish to emphasize that the prejudice that anemployee may suffer in a case of suspension is not limited to financial prejudice in the case where the suspension is without pay. Suspension with pay also has substantial prejudicial consequences relating to both social and personal standing of the suspended employee. In my view any suspension with or without pay has to bring into question theintegrity and dignity of the suspended person particularly where the suspension is based on allegations of dishonesty. And quite often suspensions attract media attention and thus the standing of the person before his or her colleagues and the community is bound to be negatively affected. It is for this reason in particular that in law theemployer is obliged to afford an employee the opportunity to be heard before the suspension. The process does not entail affording an employee an opportunity to show that he or she is not guilty of the allegations made against him or her. Affording an employee a hearing is such a simple and informal process that employers who subscribe to best labour relations practice would never have difficulty with it, because what it seeks to achieve is not only to protect the interests of the employer but also those of the employee. The interestof the employee is protected by not only giving him or her an opportunity to show why he or she should not be suspended but also protecting their dignity. It has to be remembered that at the time of suspension the person is presumed innocent. His or her guilt can only be determined at the disciplinary or pre-dismissal arbitration proceedings.

Harley v Bacarac Trading 39 (Pty) Ltd [2009] 6 BLLR 534 (LC) at page 536.

JA79/2014

MALUTI-A-PHOFUNG LOCAL MUNICIPALITY

Spijkers v Gebroerders Benedik Abattoir v Alfred Benedik en Zonen

The decisive criterion for establishing whether there is a transfer for the purposes for the directive is whether the business in question retains its identity. Consequently a transfer of an undertaking, business or part of business does not occur merely because its assets are disposed of. Instead it is necessary to consider whether the business was disposed of as a going concern, as would be indicated, inter alia by the fact that its operation was actually continued or resumed by the new employer, with the same or similar activities. In order to determine whether those conditions are met, it is necessary to consider all the facts characterising the transaction in question, including the type of undertaking or business, whether or not the businesss tangible assets, such as buildings and movable property, are transferred, the value of its intangible assets at the time of transfer, whether or not the majority of its employees are taken over by the new employer, whether or not its customers are transferred and the degree of similarity between the activities carried on before and after the transfer and the period, if any, for which those activities were suspended. It should be noted, however, that all those circumstances are merely single factors in the overall assessment which must be made and cannot therefore be considered in isolation.

Precautionary suspension. Requirements of notice of intended suspension. Particularity required not that of pleadings. Notice not required to contain evidence that there would be interference.

She was not entitled to reasons for her suspension nor was she entitled to a right to be heard before the suspension. The allegations of misconduct against her were very serious and amounted to allegations with an element of dishonesty. The contention that she could suffer possible reputational and professional prejudice was not a basis.

hearing required prior to suspension

firstly, that the employer had a justifiable reason to believe, prima facie at least, that the employee had engaged in serious misconduct; secondly that there was some objectively justifiable reason to deny the employee access to the workplace based on the integrity of the pending investigation; and thirdly that the employee was provided with an opportunity to state his case before the employer made any final decision to suspend the employee.

seeking suspension of shop stewards to be reviewed and set aside

Matter urgent; employees not having been heard; union not consulted

damage in reputation not ground for urgency

failure by an employer to comply with the provisions of a disciplinary code

Other case law cited

Highveld District Council v CCMA and Other (2002) 12 BLLR 1158 (LAC)

J1092/08

Lekabe v The Minister Department of Justice and Constitutional Development

Suspension without pay

no reason why the employer should not uplift the employees suspension

Pending hearing; Employers should refrain from hastily resorting to suspending employees

there are no valid reasons to do so; Suspensions have a detrimental impact on the affected employee and may prejudice his or her reputation, advancement, job security and fulfillment; Suspensions should be based on substantive reasons and fair procedures should be followed

Authority

No resolution

Invalid

Mogothle v Premier, North West Province (2009) JOL 23089 (LC) at [31].

suspension is the employment equivalent of arrest, with the consequence that an employee suffers palpable prejudice to reputation, advancement and fulfillment. On this basis, he suggests that employees should be suspended pending a disciplinary enquiry only in exceptional circumstances. The only reasonable rationale for suspension in these circumstances, Cheadle suggests, is the reasonable apprehension that the employee will interfere with any investigation that has been initiated, or repeat the misconduct in question.

J2127/10

Jackson v Road Traffic Management Corporation & Others

absence of a contractual right, the legal basis of the employees claim must rest on a right to fair administrative action, or the requirement of legality

Unlawful

regulation 16(1) of the Local Government: Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000

requirements

(1) the employer had to be satisfied that the employee was alleged to have committed a serious offence; (2) the employer had to establish that the continued presence of the employee at the workplace might jeopardize any investigation into the alleged misconduct, or endanger the well-being or safety of any person or property; (3) the employee had to be given an opportunity to make representations before a final decision to suspend him was taken.

Pending disciplinary hearing ; Lawfulness; Right to be heard; No such right at common law unless employee can demonstrate a right to work; employee in any event had been allowed the opportunity to respond to his suspension after the suspension occurred

Special leave then suspended

not follow own policies

special cost order

Disciplinary hearing

appeal not afforded to employee after internal hearing and dismissal

J 1520/2019

Maroleng v South African Broadcasting Corporation SOC Limited (J 1520/2019) [2022] ZALCJHB 319 (18 November 2022)

[4] These proceedings are brought in terms of section 77 (3) of the Basic Conditions of Employment Act, which extends jurisdiction to this court to hear and determine any matter concerning a contract of employment. In essence, the applicant contends that clause 5.1 of the respondents disciplinary code procedure was expressly incorporated in his contract of employment as a contractual term, and that the clause entitles him to an appeal against the decision to dismiss it.

[6]...Vakalisa v South African Weather Services and others [2017] 7 BLLR 729 (LC),...The court held that a proper reading of the rules thus did not disclose any agreement to be bound by reciprocal obligations arising from each and every policy issued by the employer. In those circumstances, there was no incorporation of the disciplinary policy by reference, and a claim for specific performance was thus not sustainable.

[10] But that is not the end of the enquiry. Even if I accept that clause 5.1 of the disciplinary code is a term of the applicants contract of employment, and one capable of surviving the termination of the applicants employment, specific performance remains a discretionary remedy. Relevant factors or grounds to be taken into account include a situation where damages would adequately compensate the plaintiff, where the order would create injustice or would be inequitable or where performance of the obligation is impossible or would produce undue hardship to the defendant (see Haynes v King Williamstown Municipality 1951 (2) SA 371 (A)). Ultimately, each case must be judged in the light of its own circumstances (see National Union of Textile Workers v Stag Packings (Pty) Ltd 1982 (4) SA 151 (T)).

[12] In summary, although the applicants right to an appeal hearing was the subject of a contractual term it is not a term that ought properly, having regard to all of the circumstances, to be the subject of an order for specific performance.

Right to representation: Union constitution outside scope of industry: it may represent its member

JA29/2021

National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) and Others v AFGRI Animal Feeds (PTY) Ltd (JA29/2021) [2022] ZALAC 99; (2022) 43 ILJ 1998 (LAC); [2022] 10 BLLR 902 (LAC) (17 June 2022)

[24] Given their legal representation, the employees were not represented in the proceedings by an office-bearer or official of that partys registered trade union in terms of section 161(1)(c). Rather, NUMSAs representation of the employees took the form contemplated in section 200(1)(b) and (c) and section 200(2), in that the union acted as a party to the proceedings on behalf of or in the interest of the employees. Where a union chooses to represent employees on this basis, this Court has recognised that it acts collectively with its members, asserting its members rights and not its own.[MacDonalds Transport Upington (Pty) Ltd v AMCU and others (MacDonalds Transport) [2016] ZALAC 32; (2016) 37 (ILJ) 2593 (LAC); [2017] 2 BLLR 105 (LAC) at para 36.]

[26] The LRA distinguishes between individual employee rights and collective bargaining rights. In MacDonalds Transport,[at para 35] in the context of arbitration proceedings, it was stated:Certainly, when a union demands organisational rights which accord to it a particular status as a collective bargaining agent vis vis an employer, it asserts and must establish [that] it has a right to speak for workers by proving they are its members; sections 11 - 22 of the LRA regulate that right. But in dismissal proceedings (which, plainly, are not about collective bargaining) before the CCMA or a Bargaining Council forum, the union is not (usually) the party, but rather the worker is the party. It is the workers right to choose a representative, subject to restrictions on being represented by a legal practitioner, itself subject to a proper exercise of a discretion to allow such representation. When an individual applicant wants a particular union to represent him in a dismissal proceeding, the only relevant question is that workers right to choose that union.[13]

[32] In GIWUSA v Maseko and others,[21] the Labour Court affirmed the approach to interpreting a constitution of a voluntary organisation as one of benevolence, rather than of nit-picking, which ought to be aimed at the promotion of convenience and the preservation of rights.[22] This is to be contrasted with the approach taken by the Constitutional Court in Lufil:The contractual purpose of a unions constitution and its impact on the right to freedom of association of its current members is founded in its constitution. A voluntary association, such as NUMSA, is bound by its own constitution. It has no powers beyond the four corners of that document. Having elected to define the eligibility for membership in its scope, it manifestly limited its eligibility for membership. When it comes to organisational rights, NUMSA is bound to the categories of membership set out in its scope.[23]

[37] However, when an employee is represented in an individual dispute with their employer by such a union, such representation is aimed at providing effective access to justice and redress to the employee, where it is due, in accordance with both sections 23 and 38 of the Constitution and prevailing labour legislation. Unlike the exercise of organisational rights in an employers workplace, the employer has no interest, in an individual dispute between it and an employee, in holding the union to the terms of the unions constitution in order to limit the employees right to representation. This is so in that the unions scope of operation relates to the industries in which the union is entitled to organise and bargain collectively. That scope does not bar the representation of a union member by that union in an individual dispute with their employer. In the context of labour relations, and given the balance of power which exists between employer and employee in the workplace, to find differently would be manifestly unfair.

delay of almost two years from the date of the incident was procedurally unfair

JR 1696/17

Independent Communications Authority of South Africa v Malapane and Others (JR 1696/17) [2022] ZALCJHB 90 (7 April 2022)

[33] The Commissioners finding that delay of almost two years from the date of the incident was procedurally unfair cannot be faulted. In Stokwe v Member of the Executive Council: Department of Education, Eastern Cape and Others,[[2018] ZACC 3.] the apex Court observed that:[71] This also accords with the general principles of how delay impacts the fairness of disciplinary proceedings. The question whether a delay in finalisation of disciplinary proceedings is unacceptable is a matter that can be determined on a case-by-case basis. There can be no hard and fast rules. Whether the delay would impact negatively on the fairness of disciplinary proceedings would thus depend on the facts of each case.

[71] This also accords with the general principles of how delay impacts the fairness of disciplinary proceedings. The question whether a delay in finalisation of disciplinary proceedings is unacceptable is a matter that can be determined on a case-by-case basis. There can be no hard and fast rules. Whether the delay would impact negatively on the fairness of disciplinary proceedings would thus depend on the facts of each case.[72] In Moroenyane, the Labour Court considered factors which this Court initially propounded in Sanderson in the context of assessing delays in criminal prosecutions, and applied those factors to determine what constituted an unfair delay in the context of disciplinary proceedings. It held:(a) The delay has to be unreasonable. In this context, firstly, the length of the delay is important. The longer the delay, the more likely it is that it would be unreasonable.(b) The explanation for the delay must be considered. In this respect, the employer must provide an explanation that can reasonably serve to excuse the delay. A delay that is inexcusable would normally lead to a conclusion of unreasonableness.(c) It must also be considered whether the employee has taken steps in the course of the process to assert his or her right to a speedy process. In other words, it would be a factor for consideration if the employee himself or herself stood by and did nothing.(d) Did the delay cause material prejudice to the employee? Establishing the materiality of the prejudice includes an assessment as to what impact the delay has on the ability of the employee to conduct a proper case.(e) The nature of the alleged offence must be taken into account. The offence may be such that there is a particular imperative to have it decided on the merits. This requirement however does not mean that a very serious offence (such as a dishonesty offence) must be dealt with, no matter what, just because it is so serious. What it means is that the nature of the offence could in itself justify a longer period of further investigation, or a longer period in collating and preparing proper evidence, thus causing a delay that is understandable.(f) All the above considerations must be applied, not individually, but holistically.

[36] Grogan J[Workplace Law (7ed) Juta at p183:] pertinently opined as follows in respect of delayed disciplinary proceedings:once the employer has established that an employee is guilty of misconduct, disciplinary proceedings should be instituted within a reasonable time. Excessive delay may estop the employer from dismissing the employee The test, essentially one of fairness is whether the employee has been under the impression that the employer has forgiven them.

[38] In sum, the Commissioner reasonably found that the fairness of the procedure was vitiated by the inordinate delay.

remorce

JR1986/20

Ndaa Food Manufacturing CC t/a Ndaa Bakery v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (JR1986/20) [2022] ZALCJHB 54 (15 March 2022)

[37] True remorse was explained in Absa Bank Ltd v Naidu and Others[(2015) 36 ILJ 602 (LAC) at para 46.] as follows: Therefore, the crucial question is whether it could be said that Ms Naidu's utterances empirically and objectively translated into real and genuine remorse. In S v Matyityi, the Supreme Court of Appeal remarked as follows on this issue:There is, moreover, a chasm between regret and remorse. Many accused persons might well regret their conduct, but that does not without more translate to genuine remorse. Remorse is a gnawing pain of conscience for the plight of another. Thus genuine contrition can only come from an appreciation and acknowledgement of the extent of one's error. Whether the offender is sincerely remorseful, and not simply feeling sorry for himself or herself at having been caught, is a factual question. It is to the surrounding actions of the accused, rather than what he says in court, that one should rather look. In order for the remorse to be a valid consideration, the penitence must be sincere and the accused must take the court fully into his or her confidence. Until and unless that happens, the genuineness of the contrition alleged to exist cannot be determined. After all, before a court can find that an accused person is genuinely remorseful, it needs to have a proper appreciation of, inter alia: what motivated the accused to commit the deed; what has since provoked his or her change of heart; and whether he or she does indeed have a true appreciation of the consequences of those actions.[38] Without the requisite remorse, it is not possible to restore the relationship of trust that forms the foundation of the employment relationship. In De Beers Consolidated Mines Ltd v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others[(2000) 21 ILJ 1051 (LAC) at para 25.] the Court said: Acknowledgment of wrong doing is the first step towards rehabilitation. In the absence of a recommitment to the employer's workplace values, an employee cannot hope to re-establish the trust which he himself has broken.

procedure: absence from disciplinary hearing

JR2868/17

Mosiapoa v South African Local Government Bargaining Council and Others (JR2868/17) [2021] ZALCJHB 310 (9 September 2021)

Old Mutual Life Assurance Co SA v Gumbi [2007] 4 ALL SA SCA

[15]...deliberate absence from the disciplinary hearing does not affect the validity of the dismissal.

charges: Gross negligence

JR2833/18

Telkom SA SOC Limited v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (JR2833/18) [2021] ZALCJHB 238 (16 August 2021)

[7] Gross negligence has been the subject of judicial commentary. In Transnet Ltd t/a Portnet v MV Stella Tingas[[2003] 1 All SA 286 (SCA) at 290-1] Scott JA defines the concept as follows:... [T]o qualify as gross negligence the conduct in question, although falling short of dolus eventualis, must involve a departure from the standard of the reasonable person to such an extent that it may properly be categorized as extreme; it must demonstrate, where there is found to be conscious risk-taking, a complete obtuseness of mind or, where there is no conscious risk-taking, a total failure to take care. If something less were required, the distinction between ordinary and gross negligence would lose its validity.

failure to follow internal prosesses

JR 1106/16

Bogoshi v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (JR 1106/16) [2021] ZALCJHB 186 (2 August 2021)

[84] I will first deal with the ground that the findings were not conveyed to the applicant in 24 hours. Whist this is a breach of the Procedure, it does not follow that the dismissal of the applicant would be procedurally unfair as a result. Any issue of procedural unfairness must be evaluated by an arbitrator based on what is contained in Item 4(1) of the Code of Good Practice.[33] That being so, one must always be guided by the following dictum in Avril Elizabeth Home for the Mentally Handicapped v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others[(2006) 27 ILJ 1644 (LC) at 1651F-H.], which has been consistently applied in this Court: It follows that the conception of procedural fairness incorporated into the LRA is one that requires an investigation into any alleged misconduct by the employer, an opportunity by any employee against whom any allegation of misconduct is made, to respond after a reasonable period with the assistance of a representative, a decision by the employer, and notice of that decision. [85] It must follow that any provisions in an employers disciplinary code and procedure containing detailed procedural prescripts in conducting a disciplinary process does not always result in a finding of procedural unfairness simply because those procedures have been contravened. I am not saying that the employer should simply ignore those provisions. It is of course true that where an employer defines its own process and sets its own procedural requirements, it should be expected to adhere to the same.[Motor Industry Staff Association and Another v Silverton Spraypainters and Panelbeaters (Pty) Ltd and Others (2013) 34 ILJ 1440 (LAC at para 44; Riekert v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (2006) 27 ILJ 1706 (LC) at para 22.] An employer that does not comply with its own disciplinary code and procedure would thus always run the risk that such failure could be found to be procedurally unfair.[Black Mountain v CCMA and Others [2005] 1 BLLR 1 (LC) at para 13, the Court held: Where the employer's disciplinary code and policy provide for a particular approach it will generally be considered unfair to follow a different approach without legitimate justification. Justice requires that employers should be held to the standards they have adopted .] However, this obligation on an employer must always be tempered by considerations of workplace efficiency,[Schwartz v Sasol Polymers and Others (2017) 38 ILJ 915 (LAC) at para 13 it was said: workplace efficiencies should not be unduly impeded by onerous procedural requirements .] and / or no prejudice being suffered by the employee due to such failure. In Rand Water Board v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others[(2005) 26 ILJ 2028 (LC) at para 9.], the court dealt with the failure by a chairperson of an appeal hearing to give reasons for her decision, which was prescribed by the disciplinary code of the employer, and held as follows: It would, in my view, be highly technical and wrong to regard such technical procedural defect on the part of the second respondent as constituting procedural unfairness justifying the compensation awarded or at all, particularly in the absence of evidence of any loss or prejudice suffered as a result thereof [86] Therefore, it may well be that even in the case of non-compliance by an employer with its own disciplinary code, that will not be procedurally unfair, based upon considerations of workplace efficiency and prejudice. This would of course be a fact specific enquiry, to be determined in each and every individual case. As held in South African Clothing and Textile workers Union and Others v Filtafelt (Pty) Ltd[(JS263/15) [2017] ZALCJHB 483 (14 November 2017) at para 114. Also compare Silverton Spraypainters (supra) at para 45.]:The point I wish to make is that procedural fairness is a holistic consideration, taking into account the provisions of the Code of Good Practice and the employers internal code and procedure. In this regard, the background events in the course of the entire disciplinary process must be considered.

procedure: right to be heard

JR 2095/16

Pilusa v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (JR 2095/16) [2021] ZALCJHB 189 (29 July 2021)

[18] The real question to be answered in this regard is whether the applicant had been afforded a right to be heard? In JDG Trading (Pty) Ltd t/a Price 'n Pride v Brunsdon,[(2000) 21 ILJ 501 (LAC) at paras 60-62.] the LAC rejected the contention rule of natural justice may be dispense with in a case of a senior employee who knew what his shortcomings were; and stated that:The opportunity which is given to a senior employee must still meet at least the two basic requirements of the audi alteram partem rule, namely, he must be given notice of the contemplated action and a proper opportunity to be heard. The reference to notice of the contemplated action necessarily implies that the action has not been decided upon finally as yet but that it is one which may or may not be taken depending on the representations which the affected person may give[] (Emphasis added)

[19] In my view, it cannot be said in the present instance that that applicant was really afforded a proper opportunity to be heard. It is hard to comprehend how was he expected to question the case of the third respondent if he was not given the details thereof prior to the disciplinary enquiry. To make matters worse, the applicant was also served with the charge sheet during the mine shutdown. It follows that the procedure that led to the applicants dismissal was not fair.

[22] In the circumstances of this case, I am satisfied that compensation that is equivalent to two months remuneration is just and equitable. The applicant was earning R22 90.00 per month at the time of his dismissal. As such, the total quantum is R45 800.00.

JR 2827/18

Madikizela v City of Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality and Another (JR 2827/18) [2021] ZALCJHB 205 (26 July 2021)

[105] First, and on the legal principles, the second respondent correctly summarized, in his award, what these are. I will suffice by saying that the Code of Good Practice in the LRA provides for consistency as a consideration in deciding the issue of the fairness of the sanction of dismissal.[Schedule 8 Item 3(6) which reads: The employer should apply the penalty of dismissal consistently with the way in which it has been applied to the same and other employees in the past, and consistently as between two or more employees who participate in the misconduct under consideration.] Where instances of inconsistency are raised as a defence to dismissal as an appropriate sanction, this would form part of the value judgment that must be exercised in deciding whether dismissal is fair.[Absa Bank Ltd v Naidu and Others (2015) 36 ILJ 602 (LAC) at paras 36 37; Consani Engineering (Pty) Ltd v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (2004) 25 ILJ 1707 (LC) at para 19.] The well-known judgment of SA Commercial Catering and Allied Workers Union and Others v Irvin and Johnson Ltd,[(1999) 20 ILJ 2302 (LAC) at para 29.] aptly determined the principles applicable to deciding inconsistency, as being: (1) Employees must be measured against the same standards (like for like comparison); (2) Did the chairperson of the disciplinary enquiry conscientiously and honestly determine the misconduct; (3) The decision by the employer not to dismiss other employees involved in the same misconduct must not be capricious, or induced by improper motives or by a discriminating management policy (in other words this conduct must be bona fide); and (4) A value judgment must always be exercised[SRV Mill Services (Pty) Ltd v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (2004) 25 ILJ 135 (LC) at para 23.]. In general, inconsistency as a consideration is intended to protect employees against arbitrary conduct by the employer. Objective difference in circumstances is thus an important consideration.[Southern Sun Hotel Interests (Pty) Ltd v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (2010) 31 ILJ 452 (LC) at para 10] As described by the Court in Bidserv Industrial Products (Pty) Ltd v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others[74]: A generalised allegation of inconsistency is not sufficient. A concrete allegation identifying who the persons are who were treated differently and the basis upon which they ought not to have been treated differently or that no distinction should have been made must be set out clearly.

urgent appliction to return electronic devices

J 748/21

Rand West City Local Municipality v Goba (J 748/21) [2021] ZALCJHB 157 (20 July 2021)

[50] No convincing reason has been put forward as to why the devices could not be handed over. In fact, it is evident from the opposing affidavit that the Respondent has not proffered a single reason or basis for his refusal to handover his laptop. The cellular phone and iPad had been subsidized by the Applicant as tools of trade for purposes of the execution of his official duties. The devices were not issued to the Respondent or subsidized for his personal use or other recreational purposes they were tools of trade. The Applicant is entitled to have access to the information on the devices, as it relates to the execution of his official duties.

JA20/2020

Sasol Mine Limited v Nhlapo and Others (JA20/2020) [2021] ZALAC 28 (9 September 2021)

[40] The obligation upon an employer to act consistently in the application of discipline arises in two contexts in our law. The first is in relation to the application of the rule and the second is in relation to the imposition of sanction.[16] In both respects there can exist either contemporaneous inconsistency or historical consistency.

Southern Sun Hotel Interests (Pty) Ltd v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation & Arbitration & others (2010) 31 ILJ 452 (LC) at para 10.

The courts have distinguished two forms of inconsistency - historical and contemporaneous inconsistency. The former requires that the employer apply the penalty of dismissal consistently with the way in which the penalty has been applied to other employees in the past; the latter requires that the penalty be applied consistently as between two or more employees who commit the same misconduct.

charges: unduly technical approach to the framing and consideration

PA12/19

Sol Plaatje Municipality v South African Local Government Bargaining Council and Others (PA12/19) [2021] ZALAC 24; [2021] 11 BLLR 1096 (LAC) (5 August 2021)

[30] It has also been repeatedly held by this Court that there is a major difference between the wording of charges in criminal matters and that of charges in disciplinary proceedings, and that an unduly technical approach to the framing and consideration of the latter should be avoided.[Pailprint (Pty) Ltd v Lyster NO and others (2019 40 ILJ 2047 (LAC) para 18; First National Bank Ltd v Language (2013) 34 ILJ 3103 (LAC).] There is also authority in this Court that if the main charge of misconduct is not proved, but an attempt to commit such misconduct is proved, the employee may be found guilty of such an attempt on that same charge.

double jeopardy and doctrine of election

JA122/2019

Anglo American Platinum Ltd v Beyers and Others (JA122/2019) [2021] ZALAC 16; [2021] 10 BLLR 965 (LAC); (2021) 42 ILJ 2149 (LAC) (2 July 2021)

[16] The primary grounds of appeal of the appellant relate to the following three main findings of the court a quo:16.1 It was incumbent upon the appellant to prove exceptional circumstances that justified its decision to review and change Mr Beyers sanction, and no such exceptional circumstances existed.

employer's prerogative

J 533/2021

Marhule v Minister of Home Affairs and Others (J 533/2021) [2021] ZALCJHB 63 (30 May 2021)

[9] The reluctance on the part of the Court to willy-nilly intervene in internal disciplinary processes or to micro-manage these processes is based on the trite principle that the prerogative to discipline remains that of the employer, and any such undue interference invariably intrudes into the employers powers and rights to take disciplinary action. Furthermore, any such intrusions and interventions do not at all serve the principle of expeditious resolution of disputes and finalisation of internal processes at the workplace.

[5] See Booysen v Minister of Safety and Security and Others [2011] 1 BLLR 83 (LAC) at para 36, where it was held;To answer the question that was before the court a quo, the Labour Court has jurisdiction to interdict any unfair conduct including disciplinary action. However, such an intervention should be exercised in exceptional cases. It is not appropriate to set out the test. It should be left to the discretion of the Labour Court to exercise such powers having regard to the facts of each case. Among the factors to be considered would in my view be whether failure to intervene would lead to grave injustice or whether justice might be attained by other means. The list is not exhaustive.See also Zondo and Another v Uthukela District Municipality and Another (2015) 36 ILJ 502 (LC); Jiba v Minister: Department of Justice and Constitutional Development and Others (2010) 31 ILJ 112 (LC) at para 17, where it was held:'Although the court has jurisdiction to entertain an application to intervene in uncompleted disciplinary proceedings, it ought not to do so unless the circumstances are truly exceptional. Urgent applications to review and set aside preliminary rulings made during the course of a disciplinary enquiry or to challenge the validity of the institution of the proceedings ought to be discouraged. These are matters best dealt with in arbitration proceedings consequent on any allegation of unfair dismissal, and if necessary, by this court in review proceedings

interdicted from invoking a secondary disciplinary process (double jeopardy)

J 528/21

Mogaladi and Another v Public Protector South Africa (J 528/21) [2021] ZALCJHB 64 (28 May 2021)

[12] See also Samson v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (D460/08) [2009] ZALC 64; (2010) 31 ILJ 170 (LC); [2009] 11 BLLR 1119 (LC) at para 12

22.1 On a general level, it is correct that an employer has a right to subject an employee to a second disciplinary inquiry on the same issue in respect of which he has already been found guilty and has had a sanction imposed upon him when it is, in all the circumstances, fair to do so[12].

Branford v Metrorail Services (Durban) and Others (DA19/2002) [2003] ZALAC 16 (13 November 2003) At para 15

22.2 Exceptional circumstances is not however the only yardstick, as fairness dictates that the interests of the employee and the employer must be brought into account. The employer is entitled to revisit the offence by means of a second disciplinary hearing, as it would be manifestly unfair for the employer to be saddled with a quick, ill-informal and incorrect decision of its employers who misconceived the seriousness of the matter and took an inappropriate decision leading to an inappropriate penalty[13].

MEC for Finance: Kwazulu-Natal and Another v Dorkin NO and Another (DA16/05) [2007] ZALAC 34; [2008] 6 BLLR 540 (LAC) (21 December 2007) At paras 10 and 14

22.3 The conduct of disciplinary hearings in the workplace where the employer is the State constitutes administrative action, which is required to be lawful, reasonable and procedurally fair. However if it can be shown that the conduct or decision was not reasonable, that action can be reviewed and set aside[14].

Ntshangase v MEC for Finance: Kwazulu-Natal & Another 2010(3) SA 201 (SCA); (2009) 30 ILJ 2653 (SCA) at para 14

22.4 The decision of the chairperson of the hearing, acting qua state employer, qualifies as administrative action and that the chairpersons decision could be reviewed on such grounds as are permissible in law which would make the decision reviewable under section 158 (1)(h) of the LRA. In such circumstances, the state as an employer was not only entitled, but bound to take the chairpersons decision on review, and that it could competently do so in terms of section 158(1)(h) of the LRA which makes clear provision for such a review on such grounds as are permissible in law[15].

Hendricks v Overstrand Municipality and Another (CA24/2013) [2014] ZALAC 49; [2014] 12 BLLR 1170 (LAC); (2015) 36 ILJ 163 (LAC)

This is so in that this Court has the power under section 158(1)(h) of the LRA to review the decision taken by a presiding officer of a disciplinary hearing on: i) the grounds listed in PAJA, provided the decision constitutes administrative action; ii) in terms of the common law in relation to domestic or contractual disciplinary proceedings; or iii) in accordance with the requirements of the constitutional principle of legality, such being grounds permissible in law[16].

SARS v CCMA & Others (Chatrooghoon) (DA 7/11) [2013] ZALAC 26; [2014] 1 BLLR 44 (LAC); (2014) 35 ILJ 656 (LAC) At para 28, where it was held;The wording of the collective agreement does not only make it abundantly clear that the chairpersons pronouncement on penalty is the final sanction...it also leaves no room for interpretation in favour of the parties having intended to provide in the collective agreement a term granting a right to SARS to substitute its own sanction for a sanction imposed by its chairperson. Whilst it is trite that the duty of trust and confidence on the part of an employee is a term implied by law in an employment contract, I do not think that such implied term extends to include, the right of an employer to substitute its own sanction for that of the chairperson, particularly...where the parties in a collective agreement elected expressly to confer on the disciplinary chairperson the sole power to impose the final sanction

Sanction

JR 82/18

Performing Arts Council of Free State v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (JR 82/18) [2021] ZALCJHB 70 (27 May 2021)

Sidumo supra n 2 at para 78; Bridgestone SA (Pty) Ltd v National Union of Metalworkers Union of South Africa and Others [2016] ZALAC 40; (2016) 37 ILJ 2277 (LAC); National Commissioner of the SA Police Service v Myers and Others (2012) 33 ILJ 1417 (LAC) at para 82-85.

[26] Given the deductions I have made above, I am satisfied that the third respondent was guilty as charged. When it comes to the sanction, the enquiry on the appropriateness thereof entails a consideration of the totality of circumstances which, inter alia, include the importance of the rule breached, the reason the employer imposed the sanction of dismissal, the basis of the employee's challenge to the dismissal, the harm caused by the employee's conduct, whether additional training and instruction may result in the employee not repeating the misconduct, the effect of dismissal on the employee and his or her long-service record.[15]

Autozone v Dispute Resolution Centre of Motor Industry & Others (2019) 40 ILJ 1501 (LAC) at paras 12-13.

While as a CEO, he was the custodian of discipline and yet he failed to lead by example or show any remorse. In my view, it is apparent from the conduct of the third respondent and the circumstances that led to his dismissal that the employment relationship is irreparably damaged and dismissal accordingly warranted.[16]

bias existed on the part of the chairperson

J119/21

Ndlovu v Chaane N.O and Another (J119/21) [2021] ZALCJHB 20 (1 March 2021)

during the brief adjournment of the proceedings...in assisting a witness to locate the document which a witness was struggling to find

the applicant is seeking a final relief which in effect extinguishes the second respondent's right to proceed with the disciplinary hearing or to discipline her at all.

[23] The exceptional circumstances calling for the Court's intervention must be found in the applicant's pleaded case and not based on arguments of a mere suspicion that she will not receive a fair hearing.

[26] There is abundance of evidence to the effect that the urgency claimed by the applicant is self-created and sadly at the expense of the tax payers.

Parity principle

JA106/2019

Nyathikazi v Public Health and Social Development Sectoral Bargaining Council and Others (JA106/2019) [2021] ZALAC 11 (26 May 2021)

[25] In this connection, it is regrettable that the approach adopted both by the second respondent and the court a quo stands in contradiction that of this Court as set out in Absa Bank Ltd v Naidu and others [2015] BLLR 1 (LAC). Ndlovu JA, after a careful analysis of the existing jurisprudence regarding discriminatory decisions with regard to dismissal stated at para 35:It is trite that the concept of parity, in the juristic sense, denotes a sense of fairness and equality before the law which are fundamental pillars of the administration of justice.The learned judge of appeal then went on to say:It ought to be realised, in my view, that the parity principle may not just be applied willy-nilly without any measure of caution. In this regard I am inclined to agree with Professor Grogan when he remarks as follows:The parity principle should be applied with caution. It may well be that employees who thoroughly deserved to be dismissed profit from the fact that other employees happened not to have been dismissed for a similar offence in the past or because another employee involved in the same misconduct was not dismissed through some oversight by a disciplinary officer, or because disciplinary officers had different views on the appropriate penalty. (at para 36).

An invalid dismissal is a nullity: Employer summarily dismissing employee because of recusal applications lodged by employee.

JA 36/2019

South African Broadcasting Corporation SOC Ltd v Phasha (JA 36/2019) [2020] ZALAC 50 (27 November 2020)

[34] The argument on behalf of the appellant was that if there was a case of wrongful dismissal, it had to be grounded in the concept of fairness. But under the reasoning employed in this judgment, the ultimate finding is that by attempting to circumvent the process in terms of s 188A of the LRA, the appellant acted unlawfully. The distinction between fairness and unlawfulness was emphasised by the Constitutional Court in Steenkamp and others v Edcon Ltd (National Union of Metal Workers of SA intervening) (2016) 37 ILJ 564 (CC) paras 189 and 192 where the court said that:An invalid dismissal is a nullity. In the eyes of the law an employee whose dismissal is invalid has never been dismissed. If, in the eyes of the law, that employee has never been dismissed, that means that the employee remains in his or her position in the employ of the employerIt is an employee whose dismissal is unfair that requires an order of reinstatement. An employee whose dismissal is invalid does not need an order of reinstatement if an employee whose dismissal has been declared invalid is prevented by the employer from entering the workplace to perform his or her duties in an appropriate case a court may interdict the employer from preventing the employee from reporting for duty or from performing his or her duties. The court may also make an order that the employer must allow the employee into the workplace for purpose of performing his or her duties. However it cannot order the reinstatement of the employees. (para 192)

[35] That must be the position in this case given the finding to which this court has arrived; that unlawfulness renders the initial decision void. And that means that the respondent is entitled to be put back into a position from which she was unlawfully removed. This finding, of course, has nothing to say about the merits of the allegations that were to be determined by the s188A process until it was subverted by appellants action to dismiss on an ostensibly separate ground. That dispute will doubtless still await determination.

substitute the sanction with that of another sanction

By Zoom or MS Teams

J 814/20

Mokoena v Merafong City Local Municipality and Another (J 814/20) [2020] ZALCJHB 135 (24 August 2020)

24.5 The applicants conduct however after the final postponement of 14 July 2020 demonstrated her outright resistance to the holding of the enquiry. Flowing from that postponement, she and her representative knew that proceedings would be held via Zoom or MS Teams. No objection was raised at the time, and no effort was made to advise the Municipality of any problems that may be anticipated in holding the hearings on a virtual platform.

24.8.1 In objecting to the convening of the hearings over the Zoom platform, it is clear the applicant had used such a platform before as evident from her legal representatives submissions, who had indeed confirmed such a fact, albeit addressing the challenges posed by Zoom[10].

24.8.6 Worst all, throughout the alleged connectivity problems that she had experienced whilst Ngcobo was at her residence, not once did the applicant make any attempt to call or contact De Swardt or the Chairperson, let alone instruct her representative to do the same, and informed them of the alleged connectivity problems.

Delay

JR 2236/17

Laubscher v General Public Service Sectoral Bargaining Council (GPSSBC) and Others (JR 2236/17) [2020] ZALCJHB 103; [2020] 10 BLLR 1053 (LC) (15 June 2020)

[54] It is trite that discipline must be brought in a prompt fashion. Failure to do so annihilates the disciplinary process and as a necessary consequence thereof that the charges against the employee could fall away in totality. In the unreported judgment of Fritz Letsoni Mohlala v The South African Post Office and Others[16], the Labour Court held that the delay in the disciplinary process was unfair and that justice delayed is justice denied.

After dismissal

JR 78/18

Zistics Transport CC v DUSWO and Others (JR 78/18) [2020] ZALCJHB 220 (7 May 2020)

Semenya v CCMA and others (2006) 27 ILJ 1627 (LAC)

The technical defence that since the disciplinary enquiry was scheduled for 17 March 2017 is not helpful to the applicant in light of the uncontested evidence of the dismissed employees. It is not unusual for an employer to hold a disciplinary hearing after a dismissal of an employee[4]. Thus, it is no answer that since a hearing was still to happen then ex hypothesi there was no dismissal factually.

Inconsistancy

JR1889/14

South African Airways Technical SOC Ltd v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (JR1889/14) [2020] ZALCJHB 58 (3 March 2020)

Bidserv Industrial Products ( Pty) Ltd v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (2017) 38 ILJ 860 (LAC) at para 31

This Court sounded a warning on approaching the question of inconsistency in the application of discipline willy-nilly without any measure of caution. Inconsistency is a factor to be taken into account in the determination of the fairness of the dismissal but by no means decisive of the outcome on the determination of reasonableness and fairness of the decision to dismiss. A generalised allegation of inconsistency is not sufficient. A concrete allegation identifying who the persons are who were treated differently and the basis upon which they ought not to have been treated differently or that no distinction should have been made must be set out clearly.

[50] It is my view that even if an employee is able to identify the persons who were treated differently and the basis upon which they ought not to have been treated differently, the enquiry does not end at that point, in that there are other factors to be considered, including but not limited to personal circumstances of individual employees, their positions and responsibilities at the workplace, the overall effect of the misconduct in question, the employees posture after the misconduct in question, including at internal disciplinary hearings and arbitration proceedings.

JR2099/16

Anglogold Ashanti Limited v Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union obo Dlungane and Others (JR2099/16) [2020] ZALCJHB 46 (20 February 2020)

National Battery (Pty) Ltd v Matshoba and Others,[(2010) 5 BLLR 534 (LC).] the court pointed out that the labels assigned to the misconduct are irrelevant the point is whether the evidence demonstrates a case of wrongdoing.

EOH Abantu (Pty) Ltd v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (2019) 40 ILJ 2477 (LAC); [2019] 12 BLLR 1304 (LAC) at paras 14 -16.

[15] One of the key elements of fairness is that an employee must be made aware of the charges against him. It is always best for the charges to be precisely formulated and given to the employee in advance of the hearing in order to afford a fair opportunity for preparation. The charges must be specific enough for the employee to be able to answer them. The employer ordinarily cannot change the charge, or add new charges, after the commencement of the hearing where it would be prejudicial to do so. However, by the same token, courts and arbitrators must not adopt too formalistic or technical an approach. It normally will be sufficient if the employee has adequate notice and information to ascertain what act of misconduct he is alleged to have committed. The categorisation by the employer of the alleged misconduct is of less importance.[16] Employers embarking on disciplinary proceedings, not being skilled legal practitioners, sometimes define or restrict the alleged misconduct too narrowly or incorrectly. For example, it is not uncommon for an employee to be charged with theft and for the evidence at the disciplinary enquiry or arbitration to establish the offence of unauthorised possession or use of company property. The principle in such cases is that provided a workplace standard has been contravened, which the employee knew (or reasonably should have known) could form the basis for discipline, and no significant prejudice flowed from the incorrect characterisation, an appropriate disciplinary sanction may be imposed. It will be enough if the employee is informed that the disciplinary enquiry arose out of the fact that on a certain date, time and place he is alleged to have acted wrongfully or in breach of applicable rules or standards. (Emphasis added)

Fairness is the hallmark of the law of dismissal

Remorse

JR1743/17

Bidair Services (Pty) Ltd v Sekhabisa N.O and Others (JR174317) [2019] ZALCJHB 328 (26 November 2019)

Absa Bank Ltd v Naidu and Others (2015) 36 ILJ 602 (LAC) at para 46. Therefore, the crucial question is whether it could be said that Ms Naidu's utterances empirically and objectively translated into real and genuine remorse. In S v Matyityi, the Supreme Court of Appeal remarked as follows on this issue:

There is, moreover, a chasm between regret and remorse. Many accused persons might well regret their conduct, but that does not without more translate to genuine remorse. Remorse is a gnawing pain of conscience for the plight of another. Thus genuine contrition can only come from an appreciation and acknowledgement of the extent of one's error. Whether the offender is sincerely remorseful, and not simply feeling sorry for himself or herself at having been caught, is a factual question. It is to the surrounding actions of the accused, rather than what he says in court, that one should rather look. In order for the remorse to be a valid consideration, the penitence must be sincere and the accused must take the court fully into his or her confidence. Until and unless that happens, the genuineness of the contrition alleged to exist cannot be determined. After all, before a court can find that an accused person is genuinely remorseful, it needs to have a proper appreciation of, inter alia: what motivated the accused to commit the deed; what has since provoked his or her change of heart; and whether he or she does indeed have a true appreciation of the consequences of those actions.

[55] Without the requisite remorse, it is not possible to restore the relationship of trust that forms the foundation of the employment relationship. In De Beers Consolidated Mines Ltd v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (2000) 21 ILJ 1051 (LAC) at para 25.

As said in De Beers supra[Id at para 22. See also Rustenburg Platinum Mines Ltd (Rustenburg Section) v National Union of Mineworkers and Others (2001) 22 ILJ 658 (LAC) at paras 21 22.]:A dismissal is not an expression of moral outrage; much less is it an act of vengeance. It is, or should be, a sensible operational response to risk management in the particular enterprise. That is why supermarket shelf packers who steal small items are routinely dismissed. Their dismissal has little to do with society's moral opprobrium of a minor theft; it has everything to do with the operational requirements of the employer's enterprise.'

doctrine of the right of election: disciplinary hearing that the sanction imposed on the Employee be amended from Final Written Warning to Dismissal.

JR444/2017

Beyers v Anglo American Platinum Ltd Mogalakwena Section and Others (JR444/2017) [2019] ZALCJHB 272; [2020] 2 BLLR 173 (LC); (2020) 41 ILJ 1376 (LC) (11 October 2019)

[18] It is common cause that the Disciplinary Code did not confer Anglo American with powers to review a chairpersons decision. Therefore, the onus was on Anglo American to prove, on balance of probabilities, that it was entitled to review its own sanction.

Samson v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (2010) 31 ILJ 170 (LC); [2009] 11 BLLR 1119 (LC) at para 11.

[12] the law as it presently stands is that an employer is entitled, when it is fair to do so (subject to the qualification that it is only in exceptional circumstances that it will be fair) to revisit a penalty already imposed and substitute it with a more severe sanction. (Emphasis added)

Country Fair Foods (Pty) Ltd v The Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (2003) 24 ILJ 355 (LAC) at paras 22 to 23.

[22] In BMW SA (Pty) Ltd v Van der Walt (2001) 21 ILJ 113 (LAC) Conradie JA cautioned against the importation of the principles of autrefois acquit into labour law. He then made two cautionary remarks:It may be that the second disciplinary enquiry is ultra vires the employers disciplinary code (Strydom v Usko Ltd [1997] 3 BLLR 343 (CCMA) at 350FG). That might be a stumbling block. Secondly, it would probably not be considered to be fair to hold more than one disciplinary enquiry save in rather exceptional circumstances (at paragraph 12).[23] In the present case appellant acted without recourse to the express provision of its disciplinary code and on the basis of no precedent. Second respondent decided that the evidence put up by appellant did not justify interference with the Kemp enquiry. In my view, there is no basis for concluding that the decision of second respondent was unjustifiable, in terms of the evidence which was presented at the arbitration hearing.[9]

Rabie v Department of Trade and Industry and Another (LC), unreported case no J515/18 (5 March 20180 at para 27.

[27] Another reason why abandoning the pre-dismissal arbitration is unlawful is that it is impermissible in terms of the doctrine of the right of election which has since been endorsed by the Constitutional Court in Equity Aviation Services (Pty) Ltd v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others.[11] The Constitutional Court referred with approval to Chamber of Mines of South Africa v National Union of Mineworkers and Another[12] where it was stated that:One or other of two parties between whom some legal relationship subsists is sometimes faced with two alternative and entirely inconsistent courses of action or remedies. The principle that in this situation the law will not allow that party to blow hot and cold is a fundamental one of general application. A useful illustration of the principle is offered in the relationship between master and servant when there comes to the knowledge of the former some conduct on the part of the latter justifying the servants dismissal. The position in which the master then finds himself is thus described by Bristowe J in Angehrn and Piel v Federal Cold Storage Co Ltd 1908 TS 761 at 786:It seems to me that as soon as an act or group of acts clearly justifying dismissal comes to the knowledge of the employer it is for him to elect whether he will determine the contract or retain the servant He must be allowed a reasonable time within which to make his election. Still, make it he must, and having once made it he must abide by it. In this, as in all cases of election, he cannot first take one road and then turn back and take another. Quod semel placuit in electionibus amplius displicere non potest (see Coke Litt 146, and Dig 30.1.84.9; 18.3.4.2; 45.1.112). If an unequivocal act has been performed, that is, an act which necessarily supposes an election in a particular direction, that is conclusive proof of the election having taken place.The above statement of the principle may require amplification in the following respect indicated by Spencer Bower Estoppel by Representation (1923) para 244 at 224 - 5:It is not... quite correct to say nakedly that a right of election, when once exercised, is exhausted and irrevocable, or in Coke's phraseology: quod semel in electionibus placuit amplius displicere non potest, as if mere mutability were for its own sake alone banned and penalized by the law as a public offence, irrespective of the question whether any individual has been injured by the volte-face. It is not so. A man may change his mind as often as he pleases, so long as no injustice is thereby done to another. If there is no person who raises any objection, having the right to do so, the law raises none. (Emphasis added)

[36] It follows that, in the absence of exceptional circumstances, Anglo Americans volte face was patently unjust to Mr Beyers; hence his objection. The dictates of modest fairness between employer and employee demand that his objection should be sustained.

Reason of dismissal is dismissal at time of dismissal

J1788/19

Mokoena v Merafong Municipality and Others (J1788/19) [2019] ZALCJHB 226; (2020) 41 ILJ 234 (LC) (13 September 2019)

Fidelity Cash Management Service v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (2008) 29 ILJ 964 (LAC) at para 32.

It is an elementary principle of not only our labour law in this country but also of labour law in many other countries that the fairness or otherwise of the dismissal of an employee must be determined on the basis of the reasons for dismissal which the employer gave at the time of the dismissal.

Trade union representation

JR2462/18

Independent Municipal and Allied Trade Union (IMATU) v South African Local Government Bargaining Council and Others (JR2462/18) [2019] ZALCJHB 240 (12 September 2019)

NUMSA v Bader Bop (Pty) Ltd and Another 2003 (3) SA 513 (CC).

[34] Of importance to the case in the ILO jurisprudence described is firstly the principle that freedom of association is ordinarily interpreted to afford trade unions the right to recruit members and to represent those members at least in individual workplace grievancesThe first principle is closely related to the principle of freedom of association entrenched in section 18 of our Constitution, which is given specific content in the right to form and join a trade union entrenched in section 23(2)(a), and the right of trade unions to organise in section 23(4)(b). These rights will be impaired where workers are not permitted to have their union represent them in workplace disciplinary and grievance matters, but be required to be represented by a rival union that they have chosen not to join

[36] Taking these two principles togetherwould suggest that a reading of the Act which permitted minority unions the right to strikefor the purposes of the representation of union members in grievances and disciplinary procedures would be more in accordance with the principle of freedom of association entrenched in the ILO Conventions.

Interpreter

JR2537/17

Hestony Transport (Pty) Limited v Venter N.O and Others (JR2537/17) [2019] ZALCJHB 175 (12 July 2019)

[35] There exists no reason why the Chairperson did not obtain the services of an Interpreter and he deviated from the preferred language despite the fact that the right to understand proceedings is a cornerstone of the LRA. The Applicant was in fact deprived of a very basic right.[36] The internal hearing was not conducted in a fair manner and the process was unfair. It therefore follows that the dismissal was procedurally unfair.

disciplinary hearing post resignation: [25] Whilst I concur with both Coetzee and Mzotsho on contractual principles, I do however disagree with the view that the employer may proceed with the disciplinary hearing without first approaching the court for an order for specific performance.

J1177/19

Naidoo and Another v Standard Bank SA Ltd and Another (J1177/19) [2019] ZALCJHB 168; [2019] 9 BLLR 934 (LC); (2019) 40 ILJ 2589 (LC) (24 May 2019)

1. The first respondent (Standard Bank of South Africa) has no power to discipline the first and second respondents subsequent to their resignation with immediate effect. 2. Standard Bank is interdicted from continuing with the disciplinary enquires against the applicants that were scheduled to commence on 16 March 2019 and 22 March 2019 respectively.

The effect of resignation

[14] In Sihlali v SA Broadcasting Corporation Ltd[1], resignation was held to be a unilateral termination of a contract of employment by the employee. Therefore, resignation brings an end to the contract of employment. In legal parlance, once an employee has resigned, he ceases to be an employee of that employer,

Toyota SA Motors (Pty) v CCMA and Others (2016) 37 ILJ 313 (CC); [2016] 3 BLLR 217 (CC); 2016 (3) BCLR 374 (CC) at para 142.

[15] It is a statutory requirement of our law, for an employee to give and serve an employer a notice period upon resignation. However, both parties may agree to waive the said notice period and the employee is free to leave. This is ideally a desirable event-free situation, however, there are instances where the employer does accept the resignation but however, wishes to hold the employee to its statutory or contractual notice period.[16] In giving effect to the principle in Toyota[3], one has to establish when does the resignation take effect. This will depend on the type of resignation: the first one will of course be resignation on notice, in this instance the resignation will only take effect at the end of the notice period. The second instance would be where an employee resigns with immediate effect, which means that the employee will not serve out his notice period and the resignation will take effect immediately.