In order to demonstrate these paradox, ironies and contradictions, it is important to analyse how society's response to youth crime has been dominated by a focus on 'welfare and or Justice', 'care and or control', 'treatment and or punishment', and latterly, there has been a return to 'justice'.

To what extent is youth justice policy vulnerable to the whims of politicians and populist calls for punishment?

Trend in Youth Justice Policy: Welfare versus Justice

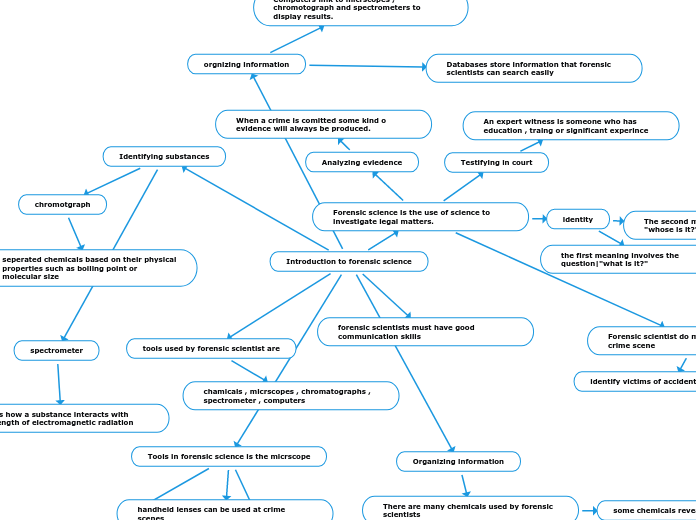

This mind map covers Section B, Question 3: Trends and Patterns in Youth Crime and Justice:

In order to engage explicitly with contemporary trends in youth justice, we need to undertake an examination of the direction of youth justice policy and practice and their relation to current trends and patterns within youth justice through rigorous scrutiny and interpretation of available evidence and data.

Juvenile Justice or youth justice practice has an especially complicated history, with widely divergent and sometimes patently contradictory tributaries flowing into the major policy and practice. Therefore, it is important to reflect upon the central themes and contested dynamics and attempt to understand that youth Justice as a system is a relative construct, often subject to the varying impulses and pressures of policy and law making.

Argument:

These themes centre around:

1. Complexities of process

2. Contradictions in practice

3. Controversies in policy making

The answer should aim to:

- summarize the key trends relating to the gateway into the youth justice system over the last decade, and

- considered what these patterns and trends tell us about how the system operates.

- undertake an examination of the direction of youth justice policy and practice and their relation to current trends and patterns within youth justice through rigorous scrutiny and interpretation of available evidence and data.

Juvenile Justice or youth justice practice has an especially complicated history, with widely divergent and sometimes patently contradictory tributaries flowing into the major policy and practice.

CONCLUSION

Main points of critical evaluation

Main points of critical analysis

Objective

Aim

Recap

INTRODUCTION

Reasoning

What was the reasoning behind these choices?

Content

What/Which research, studies, philosophies, theories, evidence have you analysed, evaluated, explored, discussed in an attempt to answer the question.

Context

In what context does the question relate to?

Objectives

How might you answer the question?

Aims:

What is the question asking?

DESCRIPTION

Throughout the development of the system of youth Justice, policy reform and developments in practice have rarely followed a linear trajectory.

Harris and Webb (1987:79) suggest the system is, "riddled with paradox, irony, even contradiction(...)exists as a function of the child are and criminal Justice system on either side of it, a meeting place of two otherwise separate worlds.

There are a number of consistent trends that define youth justice policy:

Complexities

Contradictions

Controversies

Youth justice as a system, is a relative construct.

The nature of youth justice is shaped by how a society chooses to define (construct) ‘youth offending’ at any given point in time, which in turn can influence how youth offending is explained, which in turn can influence how it is responded to through the philosophies, systems, structures, strategies, processes and practices that constitute youth justice.

This can be understood through the ‘triad of youth justice’ (Case, 2018:2): a framework for understanding that sees definitions, explanations and responses as three interrelated and mutually-reinforcing elements working together in the social construction of youth justice.

In 2005, a report by the Barrow Cadbury Trust , ‘Lost in Transition’ suggested:

“Criminal justice policies in England and Wales do unnecessary damage to the life chances of young adult offenders and often make them more, not less, likely to re-offend. They make it harder for young adults to lead crime-free lives and exacerbate the widespread problems of social exclusion that other government policies aspire to ameliorate” (2015:9).

CRITICAL EVALUATION: Youth Justice policy formation and developments within youth Justice practice.

Characterized by ‘circular motions’ (Goldson, 2015)

2009–presently: a period characterized by discernible penal moderation in the youth justice sphere.

Evidenced by the huge reductions in those entering the system.

2009-Presently: Coalition and Conservatives

Factors driving the high levels of arrests of BMAE children?

Howard league for Penal Reform (Child Arrests for England and Wales, 2017):

Increased media coverage around knife crime and gang involvement, much of which has been focused on children from non-white backgrounds” (2017:4).

Almost every time the term “knife crime” appeared in the national press last year – it was referring to black kids in London.

Much of the media reporting and political comment has been misleading:

- in part due to the paucity of reliable information on the problem

- in part due to the failure to present known facts accurately.

The response to such coverage is often a knee-jerk response and leads to a shift in emphasis towards a small, core group.

Controversy

While the aggregate harm has probably declined, it has also been concentrated on those that remain.

Evidence of a bifurcation strategy in operation:

Divert ‘low-level’ offenders away from formally entering the system.

Focus more on serious and persistent offenders.

Ethnic disproportionalities, for instance, have grown, with a larger proportion of black children and young people in the youth justice system.

Unwinding and shrinking of the youth justice system

In aggregate terms, probably causing less harm than it was when the Barrow Cadbury Trust published Lost in Transition.

1998– 2008: a decade when such punitiveness consolidated and intensified;

1991–1997: burgeoning punitiveness unfolded;

CRITICAL ANALYSIS:

Examples of Fractured Youth Justice Policy

1980's: Politicising Youth Justice

Contradiction:

Delinquents were no longer social casualties.

The White Paper titled 'Young Offender' (Home Office, 1980) shifted the emphasis from the 'child in need' to the 'juvenile criminal', culminating in the Criminal Justice Act, 1991. The act provided the appearance of a strong government with a tough on crime rhetoric.

Retreat from Welfare: 1970’s

As a result, the ‘welfare’ approach was gradually undermined by powerful sectors who had never fully supported it, such as the Conservative government:

Contradiction:

Portions of the CYPA (1969) which were retained were attacked by police and magistrates, who argued that it left them powerless to deal adequately to deal with juvenile offenders and were able to play on the perception that delinquents were running wild.

Pearson (1983:217) points out that the apparent ‘crime wave’ was totally fictitious and occurred almost entirely from the changes in police practice.

The use of formal cautioning (which was recorded) increased, replacing the informal warnings before 1969 (which were not recorded).

Welfare’ and the 1960’s

The development of a welfare-based juvenile justice policy, culminating in the Children and Young Persons Act, 1963 and 1969 were based on a consensus:

Conflict:

The Ingleby Committee (1956) was established to consider what new powers and duties could be given to local authorities to prevent the neglect of children in the home: the Ingleby Report recognised the inherent conflict when ‘justice’ and ‘welfare’ were pursued simultaneously in the same setting.

Only partial implementation of the CYPA, 1969 meant that ‘justice-based’ punitive responses (custody) reflected in the structural and organisational tensions between newly created social service departments and the juvenile youth courts- ‘classic welfare versus justice’ (Haines and Drakeford, 1998).

In stark contrast, the use of care orders and supervision orders declined.

The courts were using custody more frequently, earlier in young people’s careers, and for less serious offences.

The balance between the 'caring ethos' and the 'ethos of punishment' in youth Justice, results in a diverse and often contradictory policy domain.

For most of the eighteenth century (1700s) there was no concept of childhood in any recognizable modern sense. In other words, children tended to be expected to pass straight from physical dependence to something close to adulthood.

The period of physical dependence was taken to last up to about age 7-10. After that most children were expected to work adult hours ... and if convicted of a crime were held fully responsible and punished as adults.

In Britain and France the 1770s saw the gradual rise of the concept of an intermediate stage between physical dependence (infancy) and adulthood, namely childhood. The first books written specifically for children and some children's clothing began to appear for the first time. This development was largely confined to the middle classes, and for the poor it had to wait until well after 1850. The concept of adolescence - that is, a period between childhood and adulthood - is even more recent.

I've deliberately avoided mentioning the Enlightenment, as the beginnings

The Last 50 years or so...

Thus, within three decades we have moved from a system based on welfare priorities, care and treatment typified by the Children and Young Persons Act, 1969 to a system based on Justice, control and punishment following the Criminal Justice act, 1991.