by jonathan green 5 years ago

296

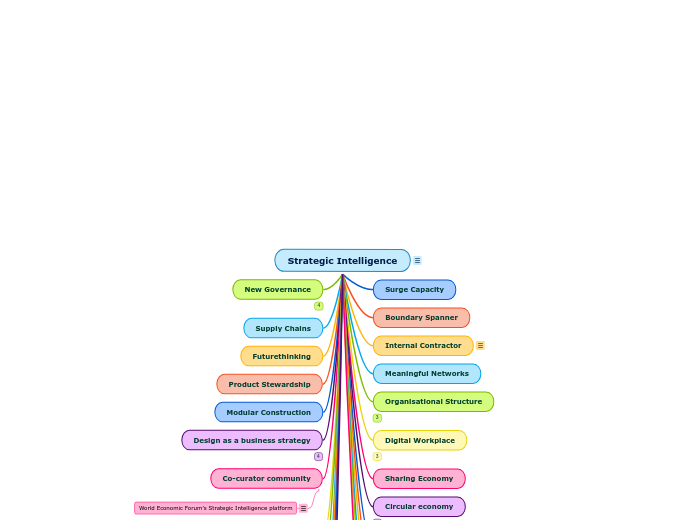

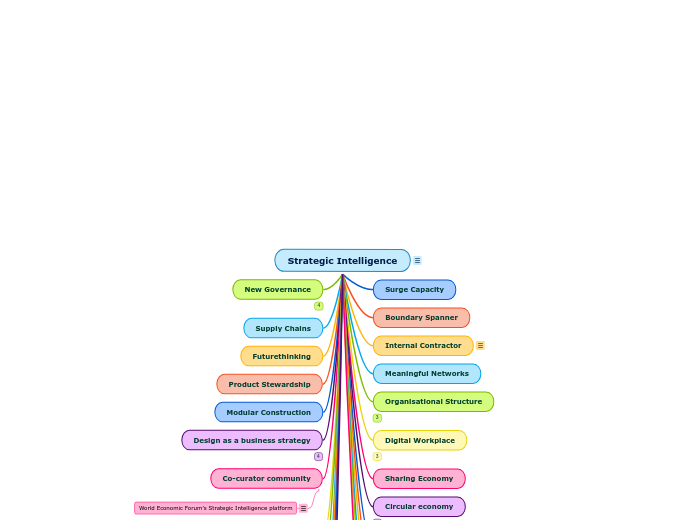

Strategic Intelligence

by jonathan green 5 years ago

296

More like this

How can you decipher the potential impact of rapidly unfolding changes when you’re flooded with information—some of it misleading or unreliable?

The World Economic Forum has developed its Strategic Intelligence

capabilities to help make sense of the complex forces driving transformational change across economies, industries, and global issues. Strategic Intelligence can help you to:

https://www.weforum.org/strategic-intelligence/

The creative economy has an abundance of renewable resources, using knowledge, experience and imagination to generate value and create goods and services that can often be developed, bought and sold, and even delivered online.

Creative Economy_ The creative economy helps to build inclusive and sustainable cultures. What’s more, it generates wealth. To build scale it requires a workforce comfortable with collaboration, critical thinking and the ability to take a risk. While many other sectors are suffering, creative individuals are blending culture and technology to generate jobs and build organisations based on generating social value and inclusion.

Declining Government InfluenceNational governments’ ability to lead change comes under greater pressure from both above and below – multinational organisations increasingly set the rules while citizens trust and support local and network based actions.

After the global financial crisis, the power and influence of the IMF, G20, the World Bank and the AIIB has come to the fore. Multinational trade agreements such as TPP and TTIP are now seeking to control pivotal standards and protocols that will influence future economic growth. Other intergovernmental organisations such as the WHO, FAO, IPCC, OECD and IEA are all variously seeking to influence future global directions. Within regions, the EU, ASEAN, GCC, African Union and OAS are, to different levels, also aiming to set the future agenda.

For some, sovereignty itself is being given away, and many national governments find that global, non-elected bodies that increasingly sit above sovereign states are deciding regional imperatives.

Greater information overload moves our focus from simply accessing data to including the source of the insight to distinguish what we trust. As connectivity increases and the information being generated around the world rises, many of us will be faced with ever more data, insight and comment that we will have to try to make sense of. As was highlighted repeatedly in the Future Agenda programme, ‘the biggest challenge is simply to manage the huge amount of data out there’. Many see that we already have too much data, are too dependent on information and this prevents us making decisions: “Too much reliance on data to guide our views has meant that we have lost intuition. Going forward we need to rise above the mass of information so that once again we can make more focused decisions.” “In many areas, knowledge is already a commodity – Wikipedia is one obvious example. If this trend increases, then where is the power? One could ask whether access to information really does empower the individual. I would say only if the recipient knows what to do with it. In the future we will move increasingly to wanting ‘data we choose’ to receive rather than just access to hard data. This could lead to a narrowing of opinions too early but clearly the successful recombination of the data received will lead to increased influence.” Many see that this information–power balance is currently in a state of flux and over the next decade could move significantly.

https://www.futureagenda.org/foresights/dynamic-pricing-2/ Supported by an overlay of predictive data analytics, flexible business models and more data, better matching supply-and-demand and improving yield is becoming possible in a host of new areas. While profit maximization is a primary driver for many businesses, this has the capability to help improve resource utilization, reduce waste and optimize system efficiencies.

https://www.futureagenda.org/foresights/companies-with-purpose/ As trust in ‘business’ declines, structures and practices of large corporations are under scrutiny. Businesses come under greater pressure to improve performance on environmental, social and governance issues. With growing realization that growth, as traditionally defined, is difficult to find in the current global economy, and particularly in the West, there is growing interest in the role of business in solving global problems rather than simply ‘making a profit’. The concept of ‘creating shared value’ has moved from academic proposition to business strategy, where companies are searching to articulate their purpose with their consumers and wider stakeholders.

Deeper CollaborationPartnerships shift to become more dynamic, long-term, democratised, multi-party collaborations. Competitor alliances and wider public participation drive regulators to create new legal frameworks for open, empathetic collaboration.Given the challenges we are facing, many see the need for a different way of working across and between organisations. The time when one company alone could develop scalable solutions is fast disappearing, and even traditional cross-industry partnerships are unlikely to have the resources and reach required. Addressing some of the big meaty future challenges will rely on deeper and wider collaboration that will no longer be driven solely by intellectual property and value considerations; instead more dynamic, agile, long-term, democratised and multi-party cooperation is on the horizon. Take rising air pollution. Tackling this will demand partnerships across transportation operators, energy providers, city planners, public health organisations, governments, regulators, financiers and citizen groups. Or, addressing the obesity challenge isn’t just about food and drink companies changing direction but also involving healthcare professionals, behavioural psychologists, regulators, transport and city planners as well as educational institutions and the media. The type of cooperation needed to innovate and address these and similar challenges will require the collaborating organisations to rethink the fundamental nature of how such partnerships are designed, operated and rewarded. Bilateral agreements, while easier to establish and execute than global ones, are implicitly limiting.The residual approach to intellectual property creation, ownership and trading is more of a barrier to collaboration that an enabler. While concepts such as patent pools have worked within industries, be that sewing machines and cars a century ago or Bluetooth, MPEG and DVD standards in the past 20 years, some see that they too are not the right model for the deeper and wider levels of collaboration envisaged for the future. The answer could be emerging in the way we increasingly collaborate around content production online via layered authorship – copyright is shared as more of us collaborate and swap ideas as thoughts are built upon again and again. As a result, multiple authors are recognised and shared information is not owned by any individual. Clearly, remuneration models for collaborative programmes need to evolve.If we are indeed going to undertake more pragmatic collaboration at scale between government, society and industry, then there will be trade-offs. With new entities and social networks joining NGOs and the state, there will be different centres of influence and leadership models. Reconciling the need for companies to work together globally and locally will involve making compromises, and we may even see a fundamental shift in how we measure success – away from GDP and income towards a more holistic perspective of progress. Some large, well-established incumbent organisations may argue for short-term incremental shifts, but it’s hoped that, in time, the big banks, energy companies and other controllers of the status quo will shift their positions. Pivotal in this shift is the expectation that many will either seek or be compelled to take a longer-term view around systemic change and that will imply wider collaboration.Within this, the role of public-private partnerships seems to be in ascendance. Although often criticised in some areas in the West, across Asia and South America the need and benefit for closer collaboration between governments and companies is evident. In Ecuador and elsewhere the successful transformation of Medellin in Colombia was highlighted as an outcome of closer public-private partnerships in city management and facility operation. In India, discussions on improving healthcare, education, transport and food supply all highlighted the potential available when more efficient execution of government ambitions can be achieved through collaboration with faster moving and more flexible private companies. Citizens, part of a shift towards more participatory government in some regions, will increasingly be more involved in both decision-making and execution. The state may take a step back and instead of leading will become the facilitator of building new relationships with people and industry that can co-create and co-provide solutions to problems.The need for greater collaboration in the future will drive many companies to re-organise themselves based more on social networks than traditional functional or business unit silos, so changing the structure of collaboration as well as the platforms upon which it operates. This could bring about a divide between meaningful networks based on shared values and emotions and those more superficial connections built purely on data. Within collaboration, time may well become a social currency, and time spent on working on collaborative projects addressing real societal issues could become the metric that drives reputation and social status. Rather than putting in cash, either from a philanthropic standpoint or as a more active investor, we may soon see a shift to individuals proactively seeking to give up their free time to help solve emerging problems, ensuring that the scale of action and impact can be far greater than that achieved when a couple of organisations decide to partner on a traditional joint venture.Already, collaboration in innovation is increasingly becoming more public and shifting from bilateral partnerships to grand challenges such as X-prizes that focus on problems currently seen to be unsolvable, or that have no clear path toward a solution. One timely example of this is the award-winning SunShot initiative run by the US Department of Energy. It focuses on accelerating the point at which solar energy becomes cost-competitive with other forms of electricity by the end of the decade – essentially bring the cost per Watt of solar energy down from $3.80 to $1. Rather than funding research within energy companies, the approach has been to first engage the wider public population to generate new concepts that could help achieve the ambition. By then funding the best ideas through cooperative research, development and deployment projects undertaken by a combination of private companies, universities, state and local governments, non-profit organizations and national laboratories, the SunShot approach is to choreograph the ideal collaboration network for each concept. Halfway into the decade long initiative, it has been able to use its resources more intelligently and fund 250 projects that have collectively already achieved 70% of the target cost reduction.Going forward, big problems are seen to require completely different ways of thinking and cooperating and deeper, wider, more meaningful collaboration is for many an important part of the puzzle.

The World Economic Forum’s Strategic Intelligence platform is a dynamic system of contextual intelligence that enables users to trace relationships and interdependencies between issues, supporting more informed decision-making. It is co-curated with leading topic experts from academia, think tanks, and international organizations. Through co-curation, the Forum ensures that public-private partnerships benefit from the insight of world-class knowledge partners. At the same time, co-curators are able to share their expertise with the Forum’s extensive network of members, partners and constituents, as well as a growing public audience. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Co_Curating_Institutions_2019.pdf

https://co-inpetto.org/danish-design-ladder/ The Danish Design Ladder was developed by the Danish Design Centre (DDC) in 2003 as a tool to measure the level of design activity in business. The Danish Design Ladder provide an assessment of how organisations actually moves up a rung on the ladder over the course of some years.The original Danish Design Ladder stops at “design as a business strategy”.Sam Bucolo adapted it by adding two more steps – ‘design as organisational transformation’ which refers to the redesign of the entire organisational structure and business model of the organisation and – ‘design as national competitive strategy’ which refers to the role of design to transform entire sectors to ensure a nation remains prosperous.

New teams at all three companies emerge in an organic manner, initiated by entrepreneurial employees. New teams only start when a group of employees gets excited about pursuing an opportunity or solving a specific problem. A new team is only launched when a group of employees is convinced that there is a demand for it. Thus, new teams emerge and grow in a free-flowing, bottom-up fashion.

At W.L. Gore new teams emerge only when at least two employees are convinced there is a real demand for the proposed idea. When the new idea needs serious investment, the employees must first pitch their idea to a committee of peers in order to get resources.

A similar thing happens at Buurtzorg, as the organization doesn't set up new teams. It relies on new teams emerging organically when a group of entrepreneurial employees sees the need for services in an area not yet served. However, new teams can only be initiated when there are at least four potential team members willing to join.

At Haier, new teams are typically initiated by groups of entrepreneurial staff via their online platforms. Employees are encouraged to share ideas online and invite others to join them in pursuing an entrepreneurial adventure. A new team only emerges when there is a minimum of three individuals willing to start the new 'microenterprise'. Like W.L. Gore, when launching investments are needed, new teams pitch their ideas to a committee of peers to request resources.

However, top-management teams hold an important role in this regard. They hold the ultimate authority to terminate or dissolve teams that are, for example, not performing up to organization standards in terms of productivity and/or client satisfaction. They also approve, or not, additional resources to teams that move beyond the existing company boundaries; for example, teams that want to explore new products, services or geographical areas.

The self-organizing teams in these companies are often small. They take one of two shapes: ad-hoc teams (W.L. Gore) and permanent teams (Haier & Buurtzorg). At W.L. Gore ad-hoc teams emerge around interactions and commitments between groups of employees. All employees can team with others to get their jobs done, and employees can be in multiple teams. Thus, W.L. Gore’s numerous small, ad-hoc teams emerge as new tasks are initiated, and dissolve once the task is done.

On the other hand, Buurtzorg organizes around >1,000 permanent, self-organizing teams, with employees being in only one team. The teams are geographically defined, each choosing their 'territory'. When a team grows beyond 12, a rule says it must split to maintain its small-scale team structure.

Similarly, Haier has split the company into >4,000 permanent teams, internally referred to as "microenterprises". The size of teams varies quite a bit, but most consist of ~10 to 15 employees. All are connected to a dedicated online platform, with platforms grouping about 50 teams.

The organization structure of large MMLOs is based on a 'network of teams' structure. Employees self-organize into teams around tasks with end-to-end responsibility. New self-organizing teams are initiated by groups of entrepreneurial employees.

The structure of all three companies is flexible and modular and consists of self-organizing teams. Employees enjoy the freedom to organize into teams to perform tasks and activities. In the teams, employees can organize however they think is best for themselves and their customers. These teams have far reaching decision-making power but are also accountable for their performance.

Haier has pushed this concept of radical decentralization to the extreme. Their self-organizing teams are run as independent companies (some even as separate legal entities) with employees sharing ownership, and being responsible for all kinds of decisions like contracting, recruitment and budgeting.

Before describing 'how' Gore, Buurtzorg and Haier organize without middle-management, we first need to agree on what exactly we mean by 'organizing'.

For this, we look at the work of scholars like Lawrence & Lorsch, Mintzberg, Burton & Obel, Birkinshaw, Puranam, Lee & Edmondson. Informed by these scholars, we argue that any functioning company (of two or more employees) should solve three intertwined problems:

The latter two can be divided into four sub-problems. 'Division of Labor' can be divided into 'Organizational Structure' and 'Task Allocation'. 'Integration of Effort’ can be divided into 'Coordination' and 'Motivation'.

This leaves 5 fundamental problems of organizing that any company, by definition, must solve:

This is the problem of defining the company's strategic direction and related objectives. This is traditionally done by a top management team that defines short-term (mostly monetary) goals.

This is the problem of separating the objectives set by top-management into tasks and roles. This is traditionally done by the introduction of a hierarchy (often with functional departments).

This is the problem of mapping tasks and roles to employees. This is traditionally done by middle management who allocate tasks and roles to employees.

This is the problem of providing employees with information they need to coordinate actions with peers. This is traditionally done by a middle management layer via rules and formalized procedures to guide and control employees.

This is the problem of monitoring the performance of employees and distributing rewards for the tasks they have performed. This is traditionally done by a middle management layer that monitors employee performance and decides the allocation of rewards.