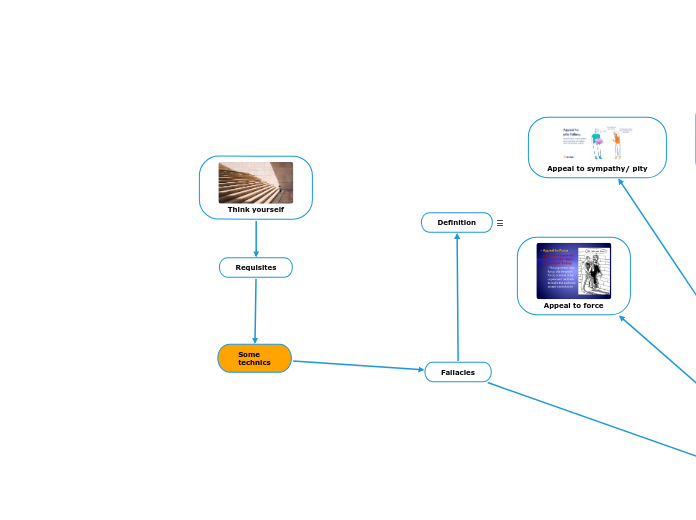

Think yourself

Requisites

Some

technics

Fallacies

Examples

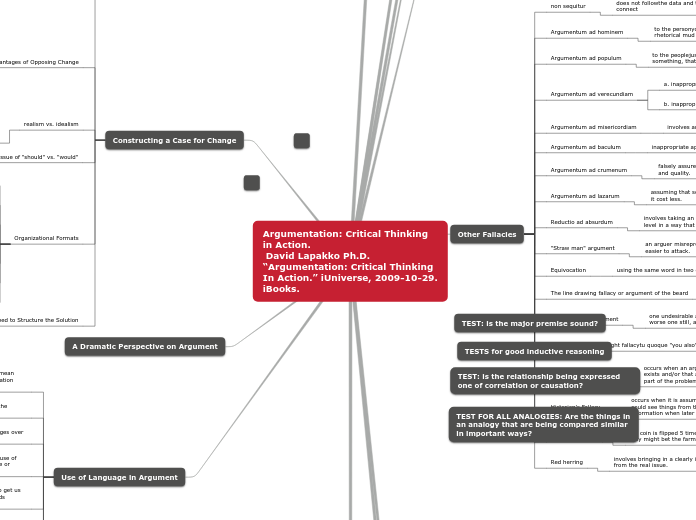

Appeal to force

Appeal to sympathy/ pity

Begging the question

(petitio principii)

The begging the question fallacy occurs when an argument’s premise relies on the conclusion.

People have known for thousands of years that the earth is round. Therefore, the earth is round.

Coca Cola is the most popular soft drink in the world. Therefore, no other soft drink is as popular as Coca Cola.

Red herring

A red herring is a misleading statement, question, or argument meant to redirect a conversation away from its original topic.

(In latin: “ignoratio elenchi")

Examples:

- If a food is cold, then it is a dessert. Salad is cold. But salad isn’t sweet, so it can’t be a dessert.

Person 1: You always leave your stuff all over the room, you don’t lock the door behind you, and the trash is piling up. You’re a slob!

Person 2: Well you never pull your car all the way into the driveway, so I’m always stuck having to park on the street!

Weak analogy

Many arguments rely on an analogy between two or more objects, ideas, or situations. If the two things that are being compared aren’t really alike in the relevant respects, the analogy is a weak one, and the argument that relies on it commits the fallacy of weak analogy.

Example: “Guns are like hammers—they’re both tools with metal parts that could be used to kill someone. And yet it would be ridiculous to restrict the purchase of hammers—so restrictions on purchasing guns are equally ridiculous.” While guns and hammers do share certain features, these features (having metal parts, being tools, and being potentially useful for violence) are not the ones at stake in deciding whether to restrict guns. Rather, we restrict guns because they can easily be used to kill large numbers of people at a distance. This is a feature hammers do not share—it would be hard to kill a crowd with a hammer. Thus, the analogy is weak, and so is the argument based on it.

Tu quoque

(you too)

The tu quoque fallacy (Latin for "you also") is an invalid attempt to discredit an opponent by answering criticism with criticism — but never actually presenting a counterargument to the original disputed claim.

In the example below, Lola makes a claim. Instead of presenting evidence against Lola's claim, John levels a claim against Lola. This attack doesn't actually help John succeed in proving Lola wrong, since he doesn't address her original claim in any capacity.

Example:

Lola: I don't think John would be a good fit to manage this project, because he doesn't have a lot of experience with project management.

John: But you don't have a lot of experience in project management either!

Ad Hominem /

against the person

An ad hominem fallacy occurs when you attack someone personally rather than using logic to refute their argument. Instead they’ll attack physical appearance, personal traits, or other irrelevant characteristics to criticize the other’s point of view. These attacks can also be leveled at institutions or groups.

Example:

Barbara: We should review these data sets again just to be sure they’re accurate.

Tim: I figured you would suggest that since you’re a bit slow when it comes to math.

Bulverism

The method of Bulverism is to "assume that your opponent is wrong, and explain his error." The Bulverist assumes a speaker's argument is invalid or false and then explains why the speaker came to make that mistake or to be so silly (even if the opponent's claim is actually right) by attacking the speaker or the speaker's motive.

The term Bulverism was humorously coined by C.S. Lewis after an imaginary character to poke fun at a very serious error in thinking that, he alleged, frequently occurred in a variety of religious, political, and philosophical debates.

The Middle Ground

This fallacy assumes that a compromise between two extreme conflicting points is always true. Arguments of this style ignore the possibility that one or both of the extremes could be completely true or false — rendering any form of compromise between the two invalid as well.

Example:

Lola thinks the best way to improve conversions is to redesign the entire company website, but John is firmly against making any changes to the website. Therefore, the best approach is to redesign some portions of the website

The Correlation

If two things appear to be correlated, this doesn't necessarily indicate that one of those things irrefutably caused the other thing. This might seem like an obvious fallacy to spot, but it can be challenging to catch in practice — particularly when you really want to find a correlation between two points of data to prove your point.

Example:

Our blog views were down in April. We also changed the color of our blog header in April. This means that changing the color of the blog header led to fewer views in April.

post hoc

This occurs when someone assumes causality from an order of events. Claiming that since B always happens after A, then A must cause B, is the problem. Order of events doesn’t necessarily mean causation.

An interesting example of correlation not being the same as causation is the relationship between ice cream sales and murder rates. Statistically, as ice cream sales rise, so do the number of murders in the area. But does one cause the other? In fact, both share the common cause of rising temperatures. As the weather gets hotter, more murders happen and more ice cream is sold.2

Slothful induction

Slothful induction is the exact inverse of the hasty generalization fallacy above. This fallacy occurs when sufficient logical evidence strongly indicates a particular conclusion is true, but someone fails to acknowledge it, instead attributing the outcome to coincidence or something unrelated entirely.

Example:

Even though every project Brad has managed in the last two years has run way behind schedule, I still think we can chalk it up to unfortunate circumstances, not his project management skills.

The Hasty Generalization

This fallacy occurs when someone draws expansive conclusions based on inadequate or insufficient evidence. In other words, they jump to conclusions about the validity of a proposition with some — but not enough — evidence to back it up, and overlook potential counterarguments.

Example:

Two members of my team have become more engaged employees after taking public speaking classes. That proves we should have mandatory public speaking classes for the whole company to improve employee engagement.

The False Dilemma

This common fallacy misleads by presenting complex issues in terms of two inherently opposed sides. Instead of acknowledging that most (if not all) issues can be thought of on a spectrum of possibilities and stances, the false dilemma fallacy asserts that there are only two mutually exclusive outcomes.

This fallacy is particularly problematic because it can lend false credence to extreme stances, ignoring opportunities for compromise or chances to re-frame the issue in a new way.

Example:

We can either agree with Barbara's plan, or just let the project fail. There is no other option.

The Appeal to Authority

While appeals to authority are by no means always fallacious, they can quickly become dangerous when you rely too heavily on the opinion of a single person — especially if that person is attempting to validate something outside of their expertise.

Getting an authority figure to back your proposition can be a powerful addition to an existing argument, but it can't be the pillar your entire argument rests on. Just because someone in a position of power believes something to be true, doesn't make it true.

Example:

Despite the fact that our Q4 numbers are much lower than usual, we should push forward using the same strategy because our CEO Barbara says this is the best approach.

Bandwagon /

ad populum

A.K.A "ad populum"

Just because a significant population of people believe a proposition is true, doesn't automatically make it true. Popularity alone is not enough to validate an argument, though it's often used as a standalone justification of validity. Arguments in this style don't take into account whether or not the population validating the argument is actually qualified to do so, or if contrary evidence exists.

While most of us expect to see bandwagon arguments in advertising (e.g., "three out of four people think X brand toothpaste cleans teeth best"), this fallacy can easily sneak its way into everyday meetings and conversations.

Example:

The majority of people believe advertisers should spend more money on billboards, so billboards are objectively the best form of advertisement.

The Straw Man

This fallacy occurs when your opponent over-simplifies or misrepresents your argument (i.e., setting up a "straw man") to make it easier to attack or refute. Instead of fully addressing your actual argument, speakers relying on this fallacy present a superficially similar — but ultimately not equal — version of your real stance, helping them create the illusion of easily defeating you

Example:

John: I think we should hire someone to redesign our website.

Lola: You're saying we should throw our money away on external resources instead of building up our in-house design team? That's going to hurt our company in the long run.

Definition

Definition: Fallacies are arguments that sound convincing but are essentially flawed; they usually stem from careless thinking or, more often, from an attempt to persuade through non-logical means.