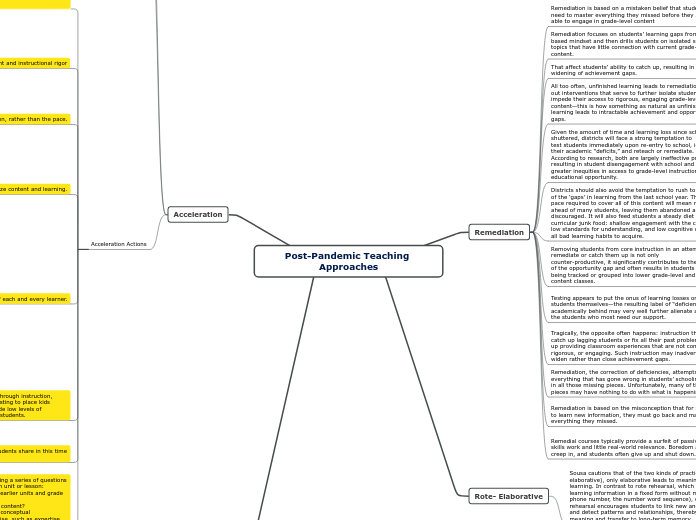

Post-Pandemic Teaching Approaches

Pandemic Study

Zearn collects data on which problems students continue to get incorrect after multiple tries, and classrooms in the acceleration group had half as many of these struggle problems as students in the remediation group. The difference was even larger in schools that served majority students of color or students in high-poverty schools.

Schwartz, S. (2021, May 24). What's the Best Way to Address Unfinished Learning? It's Not Remediation, Study Says. Education Week. Retrieved from: https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/whats-the-best-way-to-address-unfinished-learning-its-not-remediation-study-says/2021/05.

It reaffirms our finding from The Opportunity Myth that remediation can become a vicious cycle: as gaps accumulate year after year, students miss more and more grade-appropriate content in favor of review of content from previous grades and become increasingly less likely to ever make it back to grade-level mastery.

TNTP, Inc. (2021). Accelerate: Don't Remediate: New Evidence from Elementary Math Classrooms. Zearn. Retrieved from: https://tntp.org/assets/documents/TNTP_Accelerate_Dont_Remediate_FINAL.pdf.

Acceleration

Acceleration Actions

Curriculum leaders should start by asking a series of questions to determine the significance of a given unit or lesson:

1. Does the content extend work from earlier units and grade levels?

2. Does the content extend into future content?

3. Does the unit help students deepen conceptual understanding and subject area expertise, such as expertise

with mathematical practices or reading comprehension?

4. Is this content that students need to know right now in order to continue learning grade-level subject matter?

Focusing on the commonalities that students share in this time of crisis, not just on their differences.

Identify and address gaps in learning through instruction, avoiding the misuse of standardized testing to place kids

into high or low ability groups or provide low levels of instructional rigor to lower performing students.

Educators need to work to reengage students in school, emphasizing the importance of the school community and the joy of learning.

Teachers should use assessment results to alert them to the

fact that students have unfinished learning. But it is ultimately up to the teacher to identify where the gaps in essential

learning exist, and what additional scaffolding and support is required. Strong, attentive instruction, with embedded

formative assessment, thus enables teachers to respond to student needs in real-time, and in the context of grade-level standards, rather than defaulting to wholesale remediation

Maintain the inclusion of each and every learner.

What students already know about the content is one of the strongest indicators of how well they will learn new information relative to the content.

Marzano, Robert J.. Building Background Knowledge for Academic Achievement : Research on What Works in Schools, Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development, 2004. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/fullerton/detail.action?docID=3002103.

Providing students with different ways to engage in and process learning (working with a peer or in small groups, conducting interviews, critiquing the reasoning of others), and to express their learning (making presentations, sharing written explanations, making a collage) helps to reduce or eliminate barriers to showing what they know and can do.

Hirsch (2003) contends that prior knowledge about a topic speeds up learning by freeing up students’ working memory so that they can connect to new information more readily.

Vacca and Vacca (2002) explain that when students’ brains link background knowledge with new text, students are better at making inferences and retain information more effectively.

Prioritize content and learning.

What is most important to teach within the major curricular domains at each grade level. It is important that teachers know where to invest their time and effort, what areas can be cut, and where they should teach only to awareness level to save time for priorities. What is most important deserves more time, and teachers need to be given the latitude to provide responsive feedback and allow time for constructive struggle—a very different proposition than merely offering a superficial

‘right’ or ‘wrong.’

Focus on the depth of instruction, rather than the pace.

Acceleration provides a fresh academic start for students every week and creates opportunities for struggling students to learn alongside their more successful peers.

Taking the time to provide patient, in-depth instruction allows for issues related to unfinished learning to arise naturally when dealing with new content, allowing for just in time

instruction and reengagement of students in the context of grade-level work.

Stick to grade-level content and instructional rigor

This daily re-engagement

of prior knowledge in the context of grade-level assignments will add up over time, resulting in more functional

learning than if we resort to watered down instruction or try to reteach topics out of context.

To be able to accelerate unfinished learning, we need to

be able to identify what that unfinished learning of the

current grade-level essential learning is in a way that is

actionable. “

These practices support teachers in

launching the lesson to maximize student engagement,

facilitating a rich discourse through intentional questioning, and supporting students in staying engaged.

Using a rich, well-designed task

assists teachers in knowing how far to “back up” in the

prerequisite knowledge and identifies students who may

need opportunities to advance their thinking.

One way to

do so without administering broad-based diagnostics

is to use a rich, open-ended grade-level task that gives

insight into students’ understanding.

Doing so means that teachers

handpick skills or concepts “just in time” to support the

new learning, thus clearly connecting the past with the

present.

Acceleration focuses on the opportunities that students have for new learning, looks at students from an asset-based perspective, and supports their readiness for new learning.

Rote- Elaborative

Sousa cautions that of the two kinds of practice (rote and elaborative), only elaborative leads to meaningful, long-term learning. In contrast to rote rehearsal, which is a process of learning information in a fixed form without meaning (e.g., a phone number, the number word sequence), elaborative rehearsal encourages students to link new and prior learning and detect patterns and relationships, thereby creating meaning and transfer to long-term memory.

Sousa, D. (2008). How the brain learns mathematics . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Remediation

Remedial courses typically provide a surfeit of passive, basic-skills work and little real-world relevance. Boredom and futility creep in, and students often give up and shut down.

Remediation is based on the misconception that for students to learn new information, they must go back and master everything they missed.

Remediation, the correction of deficiencies, attempts to fix everything that has gone wrong in students’ schooling— to fill in all those missing pieces. Unfortunately, many of those pieces may have nothing to do with what is happening today.

Tragically, the opposite often happens: instruction that aims to catch up lagging students or fix all their past problems ends up providing classroom experiences that are not compelling, rigorous, or engaging. Such instruction may inadvertently widen rather than close achievement gaps.

Rollins, Susie Pepper. 2014. Learning in the Fast Lane: 8 Ways to Put ALL Students on the Road to Academic Success. Alexandria, VA:

ASCD.

Testing appears to put the onus of learning losses on the students themselves—the resulting label of “deficient” or academically behind may very well further alienate and isolate the students who most need our support.

Removing students from core instruction in an attempt to remediate or catch them up is not only

counter-productive, it significantly contributes to the widening of the opportunity gap and often results in students

being tracked or grouped into lower grade-level and core content classes.

Districts should also avoid the temptation to rush to cover all of the ‘gaps’ in learning from the last school year. The

pace required to cover all of this content will mean rushing ahead of many students, leaving them abandoned and

discouraged. It will also feed students a steady diet of curricular junk food: shallow engagement with the content, low standards for understanding, and low cognitive demand—all bad learning habits to acquire.

Given the amount of time and learning loss since schools were shuttered, districts will face a strong temptation to

test students immediately upon re-entry to school, identify their academic “deficits,” and reteach or remediate.

According to research, both are largely ineffective practices, resulting in student disengagement with school and

greater inequities in access to grade-level instruction and educational opportunity.

All too often, unfinished learning leads to remediation or pull-out interventions that serve to further isolate students and impede their access to rigorous, engaging grade-level

content—this is how something as natural as unfinished learning leads to intractable achievement and opportunity

gaps.

Council of the Great City Schools. 2020. Addressing Unfinished Learning after COVID-19 School Closures. https://www.cgcs.org

/cms/lib/DC00001581/Centricity/Domain/313/CGCS_Unfinished%20Learning.pdf

That affect students’ ability to catch up, resulting in a

widening of achievement gaps.

Remediation focuses on students’ learning gaps from a deficit-based mindset and then drills students on isolated skills and

topics that have little connection with current grade-level content.

Remediation is based on a mistaken belief that students

need to master everything they missed before they are

able to engage in grade-level content

Cathy Martin. (2020). Accelerating Unfinished Learning. The Mathematics Teacher, 113(10), 774–776.