Connecting

Mind & Body

to Creativity

Humanities & Creativity

Poet experiences Tao, Poet is a "manic"

The poet has experienced "Tao"

The poet as described by Plato has then indeed detached from his intellect and animal feelings. In Pirsig'sterms the poet has experienced Quality, which is 'neither a part of mind', nor a 'part of matter' but israther a 'third entity' independent of both of them.[23] It is Quality that helps us to make sense of ourexperience and it is Quality that generates the feeling. If Quality is brought into our existence it can nolonger be Quality and if we define it 'we are defining something less than quality itself'.[24] Perhaps thisis why the poet has to out of his senses, for to be in them he would not be in Quality.

Quality and "Tao"

What of Bredin/Santoro-Brienza's claim that mania becomes an 'exposition of art's specific character andvalue'. Is the specific 'character and value' the same as the value, one that stands outside a 'series ofpossible systems of value' because it is the 'sole source of all value judgements? Both Pirsig and Lewis refer to what the Chinese speak of as the Tao, 'the reality beyond all predicates... the Way in whichthings everlastingly emerge, stilly and tranquilly, into space and time'.[20]Quality (Tao) is therefore 'not a thing. It is an event... the Quality event is the cause of the subjects and objects'.[21] Pirsig came to believe that 'reality is always the moment of vision before the intellectualisation takes place — a time lapse between the 'instant of vision and the instant of awareness' that had traditionally and unjustifiably been neglected. This pre intellectual reality is Quality and 'since all intellectually identifiable things must emerge from this preintellectualreality, Quality is the parent, thesource of all subjects and objects'.[22]

Plato and Poetry

They conclude that 'poetic creation demands the abandonment of human reason and the adoption of a non-rational,nondialectical,intuitive disposition. And this is far from being defective or evil'.[10] Surely divinely inspired madness is attractivebecause only the 'best things come to us' through it. At 249deof the Phaedrus Plato again states thebenefits of someone whose experience of beauty in the earthly realm reminds him of 'true beauty'. Aperson 'gazes aloft... paying no attention to what is down below': it is this experience that brings thecharge against him of being 'mad', yet it is the 'best and noblest of all the forms that possession by godcan take'.[11]

10) Bredin, Hugh and Santoro Brienza,Liberato, Philosophies of Art and Beauty: Introducing Aesthetics,Edinburgh, 2000, p.31.

11) Cooper, John M., Editor, Plato Complete Works, Indianapolis, 1997, pp.493494.

"Good" and "us"

We know that we are in [Good's] presence and we are engaging in its nonmaterial energy.

The experience seems to beg the following questions. First, if we accept that it was Plato's desire to quash our animal feelings, and this is generally accepted by philosophers, the main problem that looms large is connected to how we feel when we are 'out of our minds' and what thought process, if any, connects us to that experience. It is all very well to say that we are apprehending beauty itself in a divine rapture and are bathed in the sunlight of the Good, but if we have transcended our animal nature,what is it that is creating any feeling at all in us? And if our intellects have been abandoned, how can we make sense of the experience?

Plato cannot define Good

Plato, however, knows that he cannot ultimately define the Good or the forms, nor provide a cast-iron theory to prove their existence. The Good is 'beyond existence'. Pirsig therefore adheres to a view that Plato and many others would agree with, namely that we can't measure beauty, nor give it a scientific definition. Any rational attempt to do so will fail; it is, to use an expression of C. S. Lewis, like trying 'tobottle a sunbeam'.[19]Plato was also no doubt aware of Quality, and probably experienced it. The reason that there is such a tension in his writing might be partly explained by his reliance on dialectic as the sole method of determining Truth, which he knew conflicted with his belief that poets don't use dialectic to achieve the experience of ultimate reality. But what is this experience like?

Plato was being subversive

It might be, as some have argued, that there is a limit to Plato's dialectical method because it provides a method for subverting the very thing to be cherished. Pirsig maintains that Plato's commitment to 'dialectically determined truth' to establish the Good as the highest truth or idea of all, usurps the Good,or to use Pirsig's term, Quality.[14] Truth, the result of the process of dialectic, must always predominate over the thing in question, in this case, the Good. Pirsig claims that 'once it's stated that the'dialectic comes before anything else', this statement itself becomes a dialectical entity, subject to dialectical reason'.[15] The conclusion drawn from this is that the real admission of truth from Plato comes in when he acknowledges his use of analogy in the Phaedrus (246b).[16]Pirsig pointed out that prior to Plato, Quality or the Good had been spoken of only by the Sophists,drawing the conclusion that the difference between Plato and the Sophists was that 'Plato's good was afixed, eternal and unmoving Idea, whereas for the rhetoricians it was not an Idea at all. The Good was not a form of reality. It was reality itself, ever changing, ultimately unknowable in any kind of fixed, rigidway'.[17] Pirsig highlights that 'Plato and Socrates are doing that which they accuse the sophists of doing— using emotionally persuasive language for the ulterior purpose of making the weaker argument, the case for dialectic, appear the stronger. We always condemn most in others... that which we fear most inourselves'.[18]

Isn't Plato himself a poet?

Although Cavarnos made a strong case for the dual nature of reason, arguing for the non discursive aspect of it to be the most important in the ascent to the Good,[13] it is not clear why the philosopher should be the only true artist able to 'gaze aloft'. Why does Plato use so much of his creative energy talking about the importance of the poet's experience, only to denigrate that knowledge? Plato arguesafter all that when the poets are in the ecstasy of creation they are freed from their irrational, basedesires. And it seems excessive for Plato to censure the poet so harshly. What human being could, evenif he had tasted divine revelation of beauty itself, ever convey the experience in language that wouldperfectly reflect that experience? The truth of the rapture felt by the poet is surely not diminished justbecause he cannot perfectly express it. Does not Plato himself resort to the 'imperfect' tools of metaphorand allegory, woven in to extremely poetic language, when he attempts to adumbrate the Good? Howwould Plato view his own writing?

Overall Issue

In light of the fundamental dualism between art and beauty in Plato's writing, and the opposing views ofhis interpreters, attempting to illuminate Plato's actual view of poetry or the creative process is anenormous challenge. It may be that Plato himself was unresolved on this matter. Is poetry truly 'divineand from the gods' or is it twice removed from the 'throne of truth' with the potential to 'deform' ourminds, worthy only of being completely abolished?

Bredin/Santoro Brienza angle

Bredin/SantoroBrienza,on the other hand, in dealing with the 'radical ambiguity in Plato's responses toart, between the philosopher and moralist on the one hand and the poet and the connoisseur on theother', have claimed that the type of divine experience of poetry contained in the narratives in thePhaedrus and the Ion, takes the place of the principle of mimesis.[9] They conclude that 'poetic creationdemands the abandonment of human reason and the adoption of a nonrational,nondialectical,intuitivedisposition. And this is far from being defective or evil'.[10] Surely divinely inspired madness is attractivebecause only the 'best things come to us' through it. At 249deof the Phaedrus Plato again states thebenefits of someone whose experience of beauty in the earthly realm reminds him of 'true beauty'. Aperson 'gazes aloft... paying no attention to what is down below': it is this experience that brings thecharge against him of being 'mad', yet it is the 'best and noblest of all the forms that possession by godcan take'.[11]

Art transcends reason

Cavarnos thus opposes Bredin/SantoroBrienza.For Cavarnos the madness of the poets is actual irrationality, contrary to reason and linked to mimesis in which lies a wealth of delusions afflicting those contemplating beauty in the earthly realm; for Bredin/SantoroBrienza,mania replaces the principle of mimesis and shows that poetry is not inferior to reason because it transcends reason. Bredin/Santoro Brienzago further to make the significant claim that mania is in fact 'an exposition of art's specific character and value'.[12]

Cavarnos angle

Why the Poet Isn't Rational

In the Republic, Plato states that in a welllivedlife a love of beauty is cultivated alongside a love oftruth. In book three he highlights benefits for children in learning about literature and music, serving as aproper foundation for the life of reason. Yet Plato wields a sledge hammer against poetry in book ten,advocating that art is a barrier to morality, affecting and stirring up unhelpful, irrational emotions in theappetitive part of the mind, and should be completely abolished. Poetry's link with the metaphysicalrealm provides the poets with a type of spiritual energy that has the power to deform the 'audience'sminds' (598b) and which the poet does not have the wherewithal to see and use properly: only thephilosopher has this insight.Cavarnos posits that the true artist, 'being a true lover of wisdom', is a philosopher.[3] He makesreference to the Apology, where Socrates, in defending his devotion to philosophy, talks about poets(22bc).Socrates realises that the poets 'do not compose their works with knowledge, but by someinborn talent and by inspiration, like seers and prophets'.[4] Socrates concludes that most bystanderswould have a better understanding of what the poets had created than the poets themselves. Cavarnosargues that the poets' creations 'cannot be considered to be the result of art' because true art is rational,while their works are 'composed when they are out of their mind', an obviously irrational state.[5]

Cavarnos highlights a principle in Plato's works from the earliest to the latest which reasons that only good can come from God, nothing evil. So, if the works of these poets really are direct manifestations of the heavenly realms then the works that they produce should be consistently good. But, using Plato's views on poetry in the Republic as a guide, the works of poets are evidently not uniformly good.Cavarnos concludes that Plato's real view about poets' creations is that they cannot come from God.When Plato mentions artists being out of their minds he is being ironical and should not be taken literally.

Poetry is representation

Cavarnos then draws us to the most potent piece of evidence used in his argument.[7] In the Laws Plato demonstrates that the godlike state is at one with representation, which Plato connects to the lower,irrational part of the soul. In book iv, 719c the Athenian says that 'when a poet takes his seat on the tripod of the Muse, he cannot control his thoughts. He's like a fountain where water is allowed to gushforth unchecked. His art is the art of representation'.[8] And, because it clouds our vision of the 'beautiful itself', it is representation that must be crushed.

Poetic Experience

In the Ion, Socrates claims that the poet experiences this rarefied atmosphere in the form of a divine'madness' that comes from the gods, channelled through the poet, who 'is not able to make poetry untilhe becomes inspired and goes out of his mind, and his intellect is no longer in him.' Socrates concludesthat 'beautiful poems are not human, not even from human beings, but are divine and are from gods;that poets are nothing but representatives of the gods, possessed by whoever possesses them' (534be).[2]Socrates discusses the need to go beyond discursive reason, implying that the whole intellect istemporarily jettisoned in the experience of the 'Beautiful itself'. Mania or divine inspiration helps the poetto transcend reason.

Ion

In the Ion, Socrates claims that the poet experiences this rarefied atmosphere in the form of a divine'madness' that comes from the gods, channelled through the poet, who 'is not able to make poetry until he becomes inspired and goes out of his mind, and his intellect is no longer in him.' Socrates concludes that 'beautiful poems are not human, not even from human beings, but are divine and are from gods;that poets are nothing but representatives of the gods, possessed by whoever possesses them' (534be).[2]Socrates discusses the need to go beyond discursive reason, implying that the whole intellect is temporarily jettisoned in the experience of the 'Beautiful itself'. Mania or divine inspiration helps the poet to transcend reason.

Alcohol & Mind Alteration

Research Developments

social cognition research

demonstrates importance

of bodily interaction to

human development

neuroscience

mirror neurons

Define: biological mechanism underlying

memetic bodily behavior

macaque monkeys

cognitive robotics

have drawn attention to

sensor "kit"

body structures

clever experimental designs

recognition priming

tap into structures

of the cognitive unconscious

powerful methods of technology

pave the way for a better understanding of sensorimotor centers in the brain that feed into higher cognitive tasks like reading texts

transcranial magnetic stimulation

fMRI scans

subjective methods:

phemenology

rejected by behaviorism

me!

The Creative Process

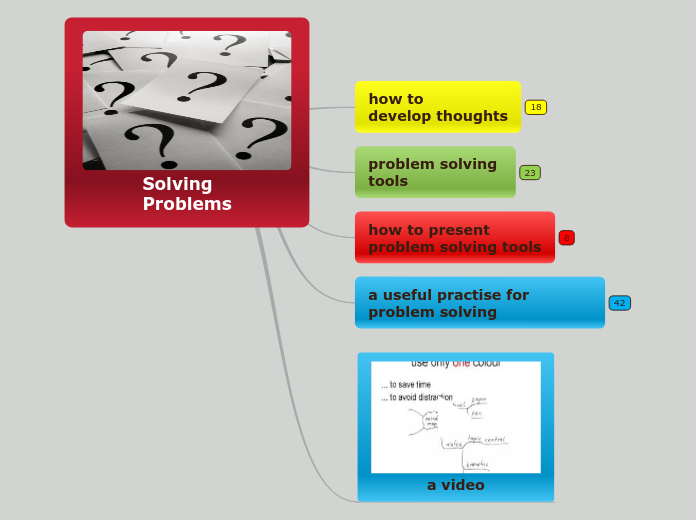

Three Stages:

preparation

incubation

translation

https://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/199203/the-art-creativity

3) Translation

With luck, immersion and daydreaming lead to illumination, when all of a sudden the answer comes to you as if from nowhere. This is the popular stage—the one that usually gets all the glory and attention, the moment that people sweat and long for, the feeling "This is it!" But the thought alone is still not a creative act. The final stage is translation, when you take your insight and transform it into action; it becomes useful to you and others.

"Ah-ha!"

2) Incubation

Once you have mulled over all the relevant pieces and pushed your rational mind to the limits, you can let the problem simmer. This is the incubation stage, when you digest all you have gathered. It's a stage when much of what goes on occurs outside your focused awareness, in the unconscious. As the saying goes, "You sleep on it."

The unconscious mind is far more suited to creative insight than the conscious mind. Ideas are free to recombine with other ideas in novel patterns and unpredictable associations. It is also the storehouse of everything you know, including things you can't readily call into awareness. Further, the unconscious speaks to us in ways that go beyond words, including the rich feelings and deep imagery of the senses.

We are more open to insights from the unconscious mind when we are not thinking of anything in particular. That is why daydreams are so useful in the quest for creativity. Anytime you can just daydream and relax is useful in the creative process: a shower, long drives, a quiet walk. For example, Nolan Bushnell, the founder of the Atari company, got the inspiration for what became a best-selling video game while idly flicking sand on a beach.

the unconscious mind

1) Preparation

The first stage is preparation, when you search out any information that might be relevant. It's when you let your imagination roam free. Being receptive, being able to listen openly and well, is a crucial skill here.

Conflicts

That's easier said than done. We are used to our mundane way of thinking about solutions. Psychologists call this "functional fixedness." We see only the obvious way of looking at a problem—the same comfortable way we always think about it. Another barrier is self-censorship, that inner voice of judgment that confines our creative spirit within the boundaries of what we deem acceptable. It's the voice that whispers to you, "They'll think I'm foolish," or "That will never work." But we can learn to recognize this voice or judgment and have the courage to discount its destructive advice.

Inside Creativity

it's for everyone

Our lives can be filled with creative moments, whatever we do, as long as we're flexible and open to new possibilities—willing to push beyond routine. The everyday expression of creativity often takes the form of trying out a new approach to a familiar dilemma. Yet half the world still thinks of creativity as a mysterious quality that the other half has. A good deal of research suggests, however, that everyone is capable of tapping into his or her creative spirit. We don't just mean getting better ideas; we're talking about a kind of general awareness that leads to greater enjoyment of your work and the people in your life: a spirit that can improve collaboration and communication with others.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/199203/the-art-creativity

"the creative spirit"

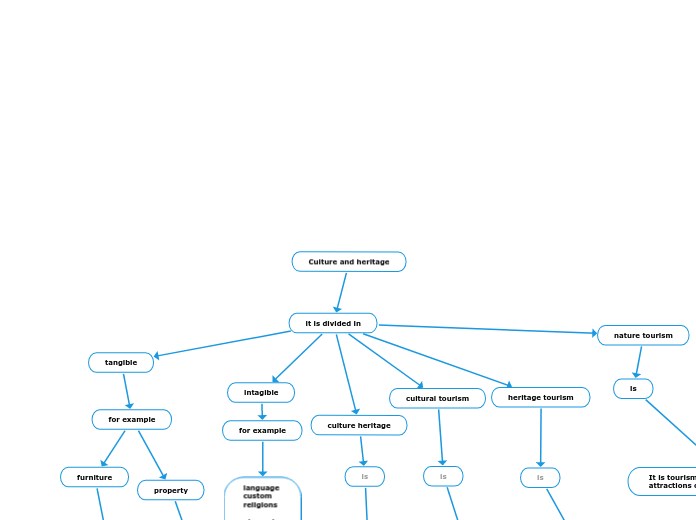

Culture

how we acquire culture

embodied cultural learning perspectives

Isolation and Loneliness

Embodiment Theory