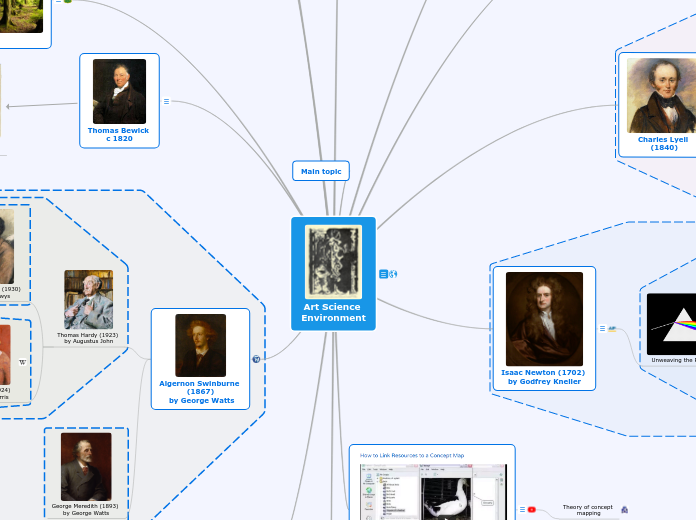

Art Science

Environment

Interior of wood by Graham Sutherland

R Tagore (1930)

by William Rothenstein

Rabindranath Tagore popularly known as Gurudev was a rare preceptor and is almost deified at Calcutta. The icon of West Bengal is relevant to the immediate present as Globalisation and Eco-concern have become the watchwords of the Twenty-first century. God, Nature and Man are inseparable entities in his poems. His sensitivity of reception has turned brooks into books and the stones as sermons. The impact of his poems are three dimensional -- emotional, intellectual and spiritual. The spiritual appeal of Gitanjali is not new. The echo of its theme in Sarojini Naidu’s Village Song and Subramaniya Bharathiyar’s Kaatru Veliyidai Kannamma lends room to a new perspective. Spiritual development in its different dimensions is vivid in this interesting comparison .The analysis of these three poems portrays how Nature is an integral aspect in providing a background, suggesting the mood and in enhancing the theme and the meaning symbolically. They also indicate the mystical progression of the soul in terms of ‘Nayika Bhava’, otherwise known as ‘Bridal Mysticism’.

Nature and Place

Nature and Place - an inner ecology for poetry

‘ I’d like to start a journal of nature poetry’ I said to a literary friend about 15 years ago.

‘Well, I wouldn’t subscribe to it’ he said ‘and I don’t think anyone else would either’, he added.

He was right at the time. I was fairly new to the contemporary poetry scene then and surprised how little of nature or of place featured as protagonist in the run of poetry in journals and new collections. Established poets like Hughes, Walcott and Heaney would often reveal that symbiosis with nature and place which I already believed to be a primary experiential resource for poetry. Poets of that period domiciled in rural areas also revealed their intimacy with the natural worlds of their habitats. But mostly poetry was as human-centred and urban as the writers presumably were in content and in spirit.

‘We don’t publish much landscape poetry’ claimed an influential editor of the time in an interview, ‘we’re looking for work that’s politically tuned and street-wise , reflecting the impression I had of the writing I saw.

This wasn’t surprising. It reflected a part of a process in modernism going back nearly a century in all the arts. Only now, confronted with the increasingly urgent news of our ravaged natural world and of our vanishing places, many poets are turning to the world outside themselves and shifting perspective – captured suddenly by what we are losing.

As psychologist I’d lectured on environmental psychology and seen the dramatic rise in research showing the impact of nature and immediate environment on human well-being: speedier recovery in hospital wards with a couple of goldfish or pot plants; worker turnover reduced by the visible presence of trees close to the workplace; profound psychic changes after wilderness experiences and so forth. Furthermore I became immersed in the philosophy and psychology of the deep green movement, pointing to a symbiosis in our relationship with the natural world, the recovery of which might change our consciousness and our ways.

It was that term ’symbiosis’ which remained with me when I began devising courses in ‘eco-poetry’. It had been ‘symbiosis’, or rather its absence, that had marked, for me, a difference between essentially 19th century writing - ( e.g. Hardy’s Woodlanders in their woods, Dickens’ human plots in the murk and dirt of London) - and that of post World-War 1 writing. The concerns manifested in literature since then have lain elsewhere - the deeply human centred - with nature and places receding into the background. That, according to the philosopher of the deep green, is a symptom of a contemporary world alienated from its natural roots. This may as yet be more marked in western contexts than in some others. Some recent cross-cultural brain research examining the perceptual processes of Westerners compared with those of East Asians found a strong tendency for the former to focus on figures as detached from the background in a visual display and for the latter to focus on context, connection and relatedness – in other words to perceive ecologically.

So what then of nature in poetry? In a splendid recent anthology of nature-inspired poetry ‘Earth Songs’, collected by Peter Abbs, one section is prefaced by the following quote from C.G. Jung:

‘man is indispensable to the completion of creation, he alone has given to the world it objective existence – without which, unheard, unseen……… through hundred of millions of years, it would have gone on in the profoundest night of non-being down to its unknown end’.

Thus according to Jung it is our observation and reaction to the natural world that offers our species its particular role among other species; our roles as scientists and poets. He is speaking, on the one hand, of the acute attentiveness to nature by biological and ecological scientists from an objective stance; but, on the other hand, of the poet, who in addition to the imaging of such qualities, responds emotionally to them thus animating them, capturing their beauty and evoking the soul of the non-human world around us.

In the courses I’ve run: ‘The Soul in Common’, ‘Common Grounds’, ‘Two-Way Mirrors’, I have tried to get participants to both engage with such qualities but also to uncover the way the natural world can infuse our inner experience, even mirror it – but only if we offer it acute attention.

But I discovered initially that many people find it hard to summon up that attention and to weave it into their passing experiences. It’s not surprising living as they do in places where nature has been extremely subdued by the human project. For example, simply considering weather, rain let’s say, their immediate reaction was to regard it entirely as facilitator or impediment to their purposes and enjoyment. So I suggested moving beyond this stance and spending time dwelling on its - its sounds, sudden appearances, light, transformation of immediate surroundings and so forth; and then how it can relate to and colour other personal experiences in the moment, revealing a symbiosis and creating in fact a poetic moment. They initially found the exercise unfamiliar and hard. For urban and suburban people –that is most of us- it’s a big challenge to find nature around us at all and if we do to be attentive to it all the time - and not just on holiday: attentive to the nature that springs out of suburban gardens, verges, roundabouts, nature in weather, skies, sunsets, diurnal and seasonal changes in light etc. these things can surround and enter our consciousness wherever we are if we let them and thus deepen emotionally our poetry and animate it.

Ecologists are already laying their groundwork for a change in awareness in our urban, suburban, often ravaged spaces with their creation of perma-culture allotments, street fruit trees, guerrilla gardening and assisting nature’s inevitable reclamation of industrial wasteland. Poets for their (essential) part can express, with their armoury of language, their receptivity to the beauty inherent in the consciousness of our emotional connection to nature.

What about place? Another milestone publication has been Jonathan Bates’ ‘Song of the Earth’. Much of it is a literary history of attitudes to nature and place. An important element in it is his discussion of our relation to places, particularly those we inhabit –for it is indeed with our habits that we leave our historic prints and through which the soul and poetry of a place is instilled. Here and elsewhere (in his a biography of the poet) he draws attention to the essentiality of home, garden and immediately surrounding terrain to the well-being and to the poetry of John Clare. Clare lived at a time when country people were materially inter-dependent and thus symbiotic with the land; but that inter-dependence was already being destroyed and its places carved up. Clare’s absolute identification with his habitat and distress at its destruction created his poetry:

‘ Oh I never call to mind/Those pleasant names of places but I leave a sigh behind/While I see the little mouldiwarps hang sweeing to the wind’

In my courses on ‘place’, as with ‘nature’ people found it initially hard to focus on a place as ‘place’, as opposed to what they did in it and who they were in it - that is a human-centred response. But we worked through different experiences of place –places loved and lost, places imagined, places feared and of course our individual home grounds; the qualities of the latter they found particularly hard to bring into awareness since their familiarity left them unnoticed. Of course the choice and mobility inherent in modern life are unlikely to provoke the intensity of John Clare’s bereavement for the loss of his home grounds. But places lost and remembered can provoke nostalgia and thus find a place in the poetic imagination.

In spite of initial barriers, as they reflected on home grounds present and past, they nevertheless began to find some emotional centres. In doing so they expanded a whole experiential zone that became important in creating poems. Indeed an important aspect of such a poetry course is the expansion of the experiential base from which people write, not only to make poems but to contribute to a shifting consciousness receptive to affirming both nature and place.

Maybe we’re returning full-circle to the recovery of destroyed places to find their history and meaning. Civic societies battle over landmarks, buildings, markets and other communal places against the incursions of new projects. Why? Because in them is inscribed the history or soul of the place. An important theme in ‘Song of the Earth’ is that poetry should be fundamentally eco-poetry; an imaginative rediscovery of ‘psycho-topology, or ‘topophilia’ (love of place) as Gaston Bachelard refers to it; an aesthetic celebration of those eco-niches where we feel ourselves to belong. From this perspective nature and place begin to re-emerge as fundamental resources for poetry.

Judy Gahagan, Nov 08

JUDY GAHAGAN

As Pessoa Says

as Pessoa says

there's nowhere you can ever be

without yourself, your irritating presence

interminably interposed

between an impulse and the lively scenes

of life beyond your eyes,

where you are not.

And Pessoa might have asked

if you thought the soul-subduing

indigo slopes of unattainable hills,

shouldering the burden of sunsets,

incandescent, night after night,

the small villages bored by day,

at night miniature Manhattans of promise,

where you also never went,

...

Algernon Swinburne

(1867)

by George Watts

George Meredith (1893)

by George Watts

Thomas Hardy (1923)

by Augustus John

Mary Butts (1924)

by Cedric Morris

Barry Cunliffe (2010)

Alexnder McIntyre

Powys's conception of Wessex in Maiden Castle is comparable to the region defined by archaeologist Barn' Cunliffe as

[A] curious, in-between, place where things are not always as they seem - a zone of merging and mixing. At various stages in history it was a place where principal actors like Arthur, Alfred and the Duke of Monmouth could vanish and reappear: a place of safety where time could be bided [...] it is a liminal zone where all things arc possible.

Cunliffe discusses the region as 'a kaleidoscope of fragments', a 'rag-quilt of discarded scraps of landscape giving rise to an amazing variety of ecozones each with its own highly distinctive character'. This concept of busy 'mixing' and 'merging*, could not offer a more pointed contrast to the seditious pastoral fiction of Man' Butts, which mobilizes an increasingly harsh rhetoric of racial purity to offset the stealthy 'insidious creep* of a 'democratic enemy' as signalled by the hordes of visitors that flock to the excavations in Maiden Castle. Whereas Cunliffe acclaims Wessex for its dizzying multiplicity and blurring of racial and social boundaries, Man' Butts promotes a single national narrative that stifles or abominates hybrid voices or 'in-between* identities.

John Cowper Powys (1930)

by Gertrude Powys

Main topic

Thomas Bewick

c 1820

The history of the medium of wood engraving evolved from the oldest printing technique, woodcut—which, in Western culture, goes back to the fifteenth century. A wood block is cut from a smoothed plank cut longitudinally from the tree trunk so that the grain runs in parallel lines to the block. Once the design has been established by cutting away the wood around the areas that will be printed, the block is inked with a small roller called a brayer. To print the block, a moistened piece of paper is placed on top of the block, along with a protective layer, called the tympan, and then put through the printing press.

Enthusiasm for the woodblock waned in Europe after the sixteenth century. In 1768, British naturalist and illustrator Thomas Bewick made his first wood engraving, using the grain side of the wood block. With this process, the block of wood is carved with a burin, an engraving tool, which creates a finer and more defined rendering than is possible with woodcut tools. Wood engraving blocks are typically made of boxwood or other hardwoods

The high reputation of Bewick’s work, interpreting nature succinctly with a series of tones varying from black to white, brought the process much acclaim. By the 1830s, the commercial ramifications of this technique were obvious: though the blocks were laboriously carved, they could be cheaply and quickly printed by letterpress, at the same time as text. Many of the block engravers were women, working freelance out of their homes. By the 1840s there were a number of firms who specialized in the manufacture of ready-prepared blocks, thus eliminating one of the time-consuming tasks of making a wood engraving.

Paul Nash (1922)

Self portrait

Eric Ravillious (1933)

by Michael Rothenstein

Treekind

The concept of tree kind was common ground for many landscape painters, notably under the influence of Samuel Palmer.

John Evelyn

The history of the house and grounds of Felbrigg Hall was narrated by the last private owner, Robert Wyndham Ketton-Cremer, in 'Felbrigg: The Story of a House'.

The house was built in the early 17th century, on the site of the old Felbrigg Manor, surrounded by heaths and patches of native woodland. Windhams and Wyndhams from different lines of the family married and intermarried for the next 250 years. The)' dabbled in politics, went on grand tours, got stung during the South Sea Bubble, built up a sizeable estate. In 1676. William Windham I, a disciple of John Evelyn, began a tree nursery, which he sowed with native tree seed and planted up with local saplings. The 70 beeches came from the nearby woods at Edgefield.

Samuel Palmer (1829)

by George Richmond

Graham Sutherland (1977)

Self portrait

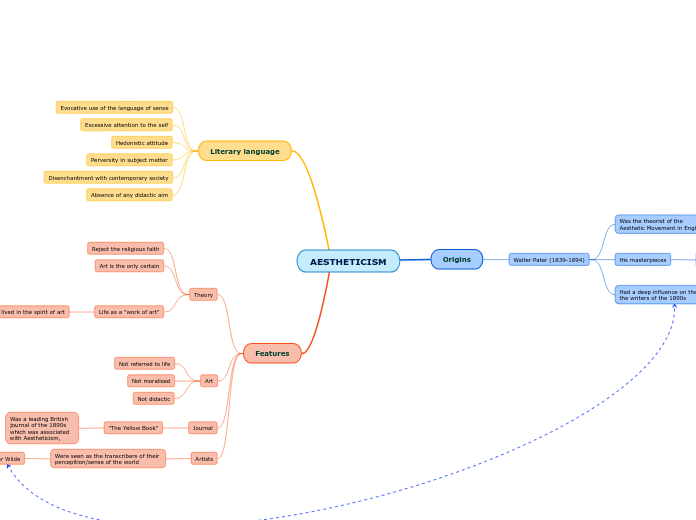

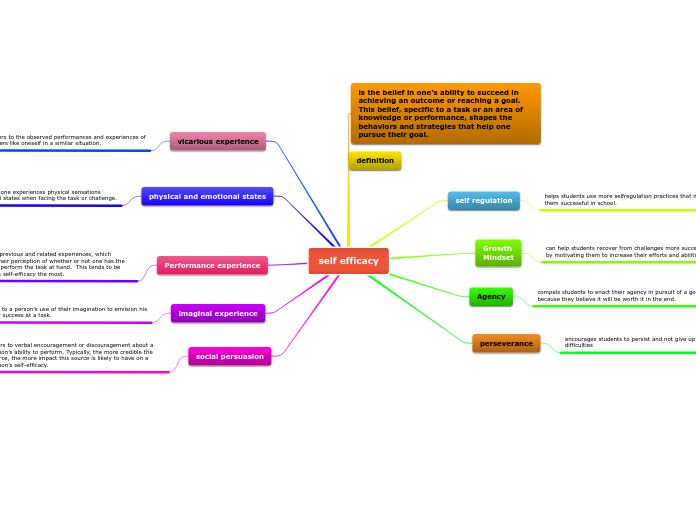

Concept mapping

According to the “dual-coding” theory of information storage , information is processed and stored in memory in two forms: a linguistic form (words or statements) and a nonlinguistic, visual form (mental pictures or physical sensations). The way knowledge is coded in the brain has significant implications for teaching and particularly for the way we help students to learn. The primary way we present new knowledge to students is linguistic. We either talk to them about the new content or have them read about it.

The fact that education gives weight to the verbal processing of knowledge means that students are left to generate their own visual representations. Yet, it is well established that showing children how to represent information using the imagery form not only stimulates but also increases activity in the brain. As students try to convey what they know and understand in nonlinear, visual ways, they are forced to draw together what they have learned; see how ideas, information, and concepts are connected; develop higher-order thinking skills (e.g., analytical thinking); and organize their knowledge in a way that makes sense to others. Visual representations also help students remember and recall information more easily.

Visual representations can be created and supported by tools such as graphic organizers, physical models, pictographs (i.e., symbolic pictures), and engaging students in kinesthetic activities, that is, activities that involve physical movement (Marzano, Pickering, & Pollock, 2001). From those, perhaps the most commonly used visual learning tool is graphic organizers, which include diagrams depicting hierarchical information (e.g., concept maps), time-sequence patterns (e.g., chain of events, time lines), cause-effect relationships (e.g., fishbone diagrams), comparisons (e.g., Venn diagrams), free associations and links among ideas (e.g., webs or mind maps), and how a series of events or stages are related to one another in a repeating process (e.g., life cycle diagrams). Graphic organizers help students not only to “read” and comprehend more easily complex information and relationships but also to generate ideas, structure their thoughts, and learn how to make visible, in an easy-to-read way, what they know. The latter requires that students understand the topic under study, be able to discern relationships between concepts, and prioritize information.

Theory of concept

mapping

Isaac Newton (1702)

by Godfrey Kneller

Newton's remarkable intellectual accomplishments include creation of the calculus, invention of the reflecting telescope, development of the corpuscular theory of light, and development of the principles of gravity and terrestrial and celestial motion. A "Newtonian" worldview came to permeate understanding not only of the physical world, but also of such intellectual fields as politics and economics—in which people now sought simple and universal laws of the type demonstrated by Newton in physics and astronomy. The debate about the incompatibility of the arts and science, the two cultures, began when William Blake used Newton's work to make the point that scientific explanations for environmental phenomena take away their beauty.

Unweaving the Rainbow

Unweaving the Rainbow (subtitled "Science, Delusion and the Appetite for Wonder") is a 1998 book by Richard Dawkins, discussing the relationship between science and the arts from the perspective of a scientist.

John Keats' "LAMIA'

written 1820

Information aesthetics

Because mind maps reflect the structure of their author’sthought process on a given subject, they are useful for ideageneration (i.e., creatively filling in “gaps” in a map) as wellas understanding the author’s conception of a problem domain. Mind maps are used to representand synthesize field research data, and to study topics such as computer-supported creativity .With the explosion of the Internet and ubiquitous computingin recent years, tasks that have traditionally been done with paper and pencil are moving into the digital realm. Numerousdigital mind mapping tools have consequently emerged, suchas Mindjet’s Mindmanager, Buzan’siMindMap and FreeMind.

These tools have largelyreplicated the functionality of mind mapping in the virtualrealm, allowing users to create visual graphs connected bylines and descriptive text using a keyboard and mouse

Charles Lyell

(1840)

Darwin & Wallace

Charles Kingsley

(c 1860)

Kingsley had earned himself quite a reputation as clergyman-novelist-naturalist and was well-known for his religious fervour. However, he could not "give up the painful and slow conclusion of five and twenty years' study of geology, and believe that God has written on the rocks one enormous and superfluous lie."'6 He repeatedly asked his readers to use their common sense and not to believe in a Deus quidam deceptor "who puts shells upon mountain-sides only to befool honest human beings."

K ingsley was a keen amateur geologist whose role in geology was not that of an original contributor. Nevertheless, he was made a fellow of the Geological Society in 1863, upon the proposal of Charles Bunbury," seconded by Lyell. His is the work of a fervent amateur scientist who sided decidedly with the scientists but never doubted God's hand in the creation. "You must not confound Madam How and Lady Why. Many people do it, and fail into great mistakes thereby," Kingsley writes in his "lessons in earth lore for children."19 He is one of those few clergymen-geologists who accepted the conclusions of science but whose faith could not diminish the grandeur of the Creator. He welcomed Darwin's Origin of Species without reserve. His writings, therefore did not eschew either science or religion:

Sauel T Coleridge (1795)

by Peter van Dyke

As a youth, the poet Coleridge was a radical inspired by the French Revolution. With Robert Southey he planned to emigrate to America to establish a 'pantisocratic' society of equals. In 1798, his collaboration with William Wordsworth culminated in Lyrical Ballads which, with Wordsworth's later 'Preface' (1800), became a manifesto for revolutionary poetics.

Coleridge's most successful poems include the visionary Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798), Frost at Midnight (1798) and Kubla Khan (1816)

Wordsworth (1842)

by Bebjamin Haydon

Tennyson

The midpoint of the nineteenth century marks the division between "the era of Wordsworth" and the "era of Tennyson." In April of 1850 Wordsworth died, and in November Tennyson was appointed to succeed him as Poet Laureate. Then, within weeks of each other, the two great autobiographical poems of the century were published. One, subtided the "Growth of a Poet's Mind," embodies the spirit of the Romantic Age just passed; the other, sometimes called "The Way of the Soul," illuminates a new vision that developed during the reign of Victoria.

William Blake (1807)

by Thomas Phillips

Between 1795 and 1805, the mystic poet, painter and printmaker William Blake produced a print that he titled "Newton" . Blake's Newton holds a compass. To Blake, this compass represented an instrument that clips the wings of imagination. Blake was a strong opponent to some of the aspects of the movement of the Enlightenment and its attempts to explain nature and all phenomena within it. In his view, Newton and the empiricist philosophers Francis Bacon and John Locke all conspired "to unweave the rainbow." Stressing that he was part of a creative, artistic world. Blake went so far as to declare:

"Art is the tree of life.

Science is the tree of death."

Somewhat similar sentiments were expressed by Blake's contemporary, the young poet John Keats, who wrote:

"Philosophy will clip an Angel's wings

Conquer all mysteries by rule and line,

Empty the haunted air, and gnomed mine --

Unweave a rainbow..."