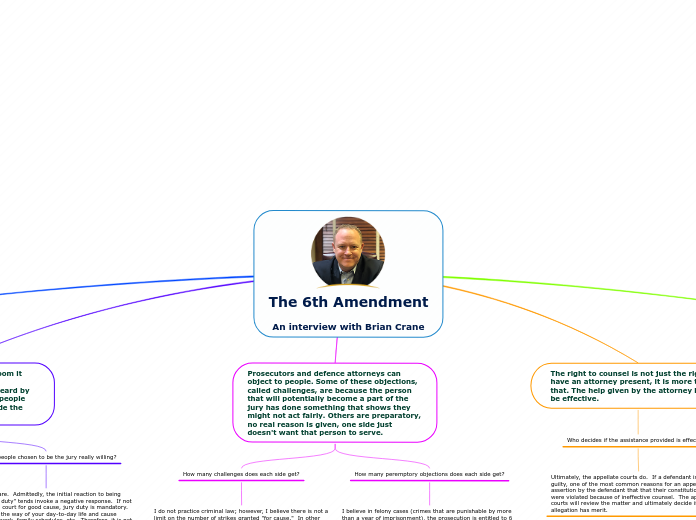

The 6th Amendment

An interview with Brian Crane

This mind map comes in handy if you are in the middle of job searching. Gather all the possibilities, then with the help of the mind map choose whichever fits your needs best.

Questions about Brian's experience

Can you tell me about your experience?

My experience as an attorney has been rewarding at times, frustrating at others. I like being an attorney because I can help my clients solve their problems or avoid getting into problems. The legal system is a very important to protect people, their property, and their rights as guaranteed by the Constitution.

What did you have to go through to become a lawyer?

To become an attorney, I had to do the following steps in order: attend high school, graduate from high school, apply to college, get accepted into college, attend college, graduate from college, apply to law school, get accepted into law school, attend law school, pass the bar examination in the state where I practice law (Pennsylvania), and take an oath before a Judge that I promise to follow and defend the Constitution of the United States and the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

How do you use the Constitution in your work?

The Constitution is the foundation of our legal system. The Constitution guarantees that no person shall be deprived personal property or liberty without due process of law. "Due process", in essence, means the right to receive notice of the allegations against you and the right to be heard on your side of the story. While I do not argue constitutional law matters in my work, I am very much reliant upon the guarantees that it affords me and my clients.

The right to counsel is not just the right to have an attorney present, it is more than that. The help given by the attorney has to be effective.

Who decides if the assistance provided is effective?

Ultimately, the appellate courts do. If a defendant is found guilty, one of the most common reasons for an appeal is an assertion by the defendant that that their constitutional rights were violated because of ineffective counsel. The appellate courts will review the matter and ultimately decide if the allegation has merit.

Prosecutors and defence attorneys can object to people. Some of these objections, called challenges, are because the person that will potentially become a part of the jury has done something that shows they might not act fairly. Others are preparatory, no real reason is given, one side just doesn't want that person to serve.

How many peremptory objections does each side get?

I believe in felony cases (crimes that are punishable by more than a year of imprisonment), the prosecution is entitled to 6 peremptory challenges and the Defendant is entitled to 10.

How many challenges does each side get?

I do not practice criminal law; however, I believe there is not a limit on the number of strikes granted "for cause." In other words, if the Judge determines a prospective juror cannot be fair, he may allow them to be stricken "for cause." Again, Constitution guarantees the right to an impartial jury. If a potential juror cannot be impartial, he/she should not be permitted on the jury.

In an article by Annenburg Classroom it says, one of the rights in the 6th amendment is to have your case heard by an impartial jury, which is willing people from the surrounding area to decide the case based on the evidence.

Are the people chosen to be the jury really willing?

I believe they are. Admittedly, the initial reaction to being called for "jury duty" tends invoke a negative response. If not excused by the court for good cause, jury duty is mandatory. This can get in the way of your day-to-day life and cause problems with work, family schedules, etc. Therefore, it is not uncommon for people to try to "get out of jury duty" claiming the disruption to their schedule would cause a significant hardship. However, once a jury is selected. I believe the jury takes their role seriously.

How is the jury chosen?

A jury is chosen from a pool of potential jurors called a "jury panel." The jury panel is comprised of a group of random citizens within the community. The attorneys for each side get to ask the potential jurors questions to determine whether anyone in the jury pool is biased. This process is called "voir dire." If an attorney feels that a juror is biased, they can "strike" them from the juror pool. Each side gets a set number of "peremptory challenges/strikes" to remove any juror they want; however, a juror cannot be removed based on their race. Also, the judge can remove a juror if he/she finds they cannot decide the case impartially.

The 6th amendment promises a speedy and public trial for people accused of a crime.

How is the public kept informed?

The public is kept inform by the press and public records/filings. News reporters tend to cover "high profile" cases. These cases involve either a well-known defendant (someone famous) or a particularly sensitive and/or salacious fact pattern. High profile cases tend to draw a lot of interest from the public and therefore draw the public to the reporter's newspapers, channels, and websites.

Many court case filings are available to the public. The public can access various criminal complaints, scheduling orders, and docket sheets. A docket sheet is a document in kept in the county prothonotary's office which keeps track of what is happening with a particular case.

How long does it usually take for a criminal to get his/her trial?

The 6th amendment guarantees criminal defendants the right to a speeding and public trial by an impartial jury. Significantly, the constitution does not list a specific time frame as to what constitutes a "speedy trial." This is because different types of cases require different amounts of time to prepare and to ultimately bring before a jury. The more serious and complex the case, the longer it may take the parties to prepare their case and/or defense. The courts will interpret this constitutional guarantee under a "reasonableness standard." How long was the delay? Why was there a delay? Was the Defendant prejudiced due to the delay?

Once arrested, the defendant will likely be indicted within 30 days. A defendant charged with a less serious offenses (i.e. misdemeanors or infractions) may go to trial within a month or two of his/her indictment. More serious crimes can, in some cases, take years.