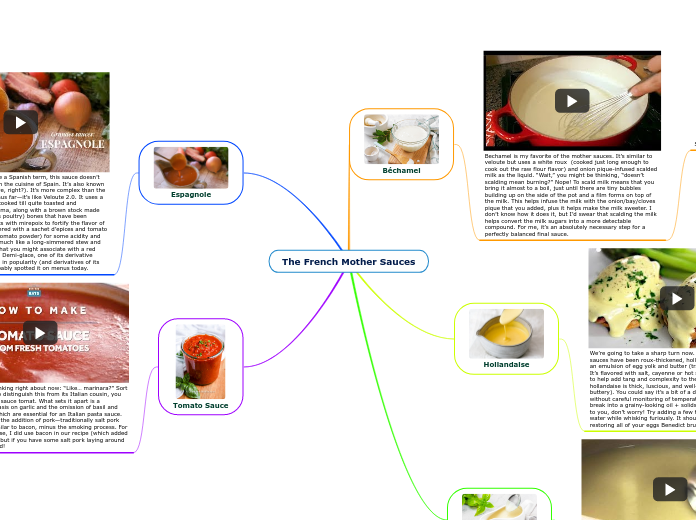

The French Mother Sauces

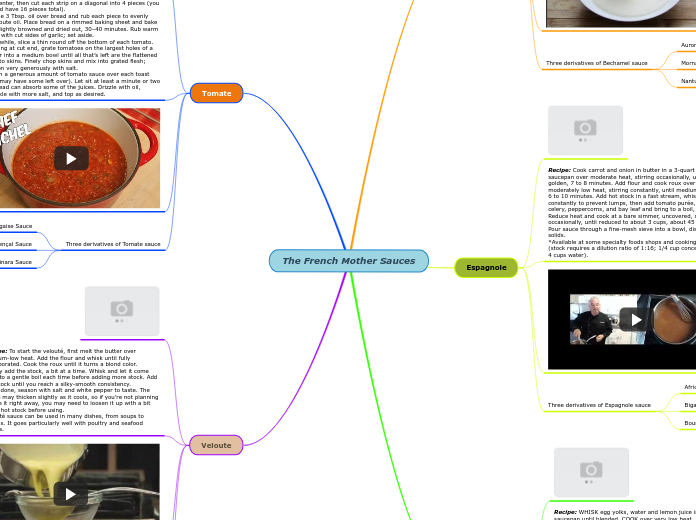

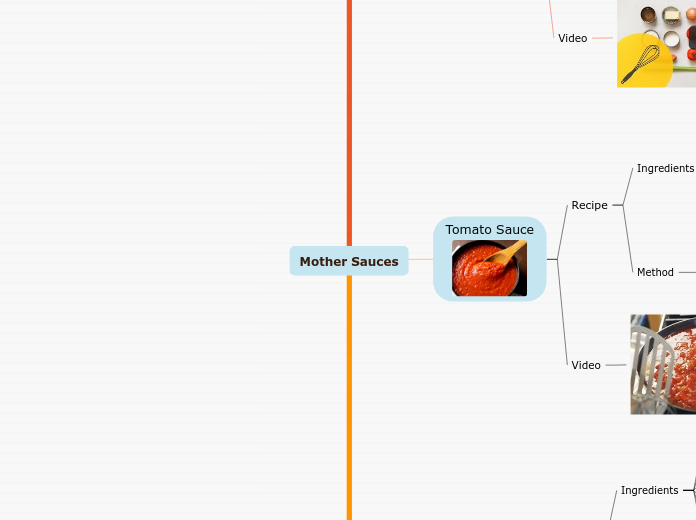

Tomato Sauce

You might be thinking right about now: “Like… marinara?” Sort of! If you want to distinguish this from its Italian cousin, you can refer to it as sauce tomat. What sets it apart is a decreased emphasis on garlic and the omission of basil and oregano, all of which are essential for an Italian pasta sauce. You’ll also notice the addition of pork—traditionally salt pork which is very similar to bacon, minus the smoking process. For simplicity and ease, I did use bacon in our recipe (which added a hint of smoke) but if you have some salt pork laying around—use that instead!

Creole = tomato sauce + green bell pepper + celery + hot sauce or cayenne

Milanaise = tomato sauce + mushrooms + ham

Espagnole

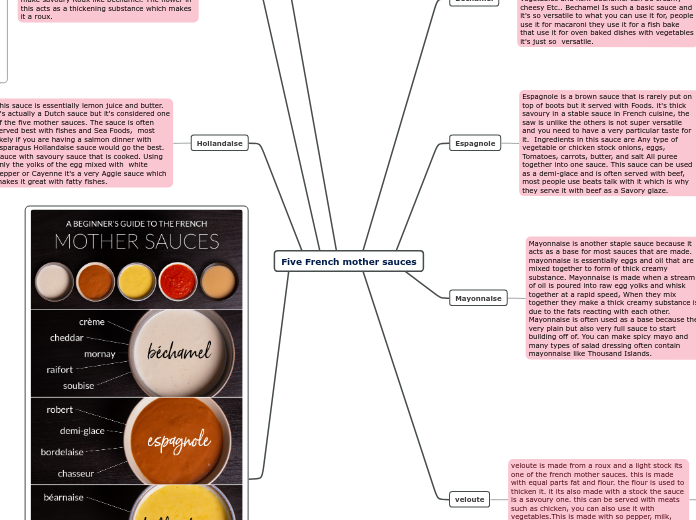

While it might sound like a Spanish term, this sauce doesn’t have anything to do with the cuisine of Spain. It’s also known as Brown Sauce (creative, right?). It’s more complex than the sauces we’ve covered thus far—it’s like Veloute 2.0. It uses a brown roux, one that’s cooked till quite toasted and distinctively nutty in aroma, along with a brown stock made with beef (or sometimes poultry) bones that have been roasted. The sauce starts with mirepoix to fortify the flavor of the stock, then is simmered with a sachet d’epices and tomato puree (our recipe uses tomato powder) for some acidity and umami notes. It tastes much like a long-simmered stew and even has some flavors that you might associate with a red wine-braised beef roast. Demi-glace, one of its derivative sauces, rivals espagnole in popularity (and derivatives of its own) and you have probably spotted it on menus today.

Demi-glace = 50% espagnole + 50% brown stock and reduced by half

Robert = demi-glace + mustard + onion + white wine + sugar

Veloute

Let’s start out simple. You’ve probably already made veloute! It’s basically what you’d think of as gravy, and you’ve probably used turkey drippings to make something similar on Thanksgiving. Veloute specifically refers to a sauce made with white stock—like veal, seafood, or chicken. It starts with a blond roux, one that’s cooked until lightly toasted and aromatic. It then gets the stock addition. A simmer helps thicken the sauce and reduce flavors, then it’s ready to serve! See? Easy.

Vin Blanc = veloute + dry white wine

Normandy/Normande = fish veloute + mushrooms + cream + egg yolks

Hollandaise

We’re going to take a sharp turn now. Where the rest of the sauces have been roux-thickened, hollandaise is composed of an emulsion of egg yolk and butter (traditionally: clarified). It’s flavored with salt, cayenne or hot sauce, and lemon juice to help add tang and complexity to the richness. Done well, hollandaise is thick, luscious, and well-balanced (not just buttery). You could say it’s a bit of a diva though because, without careful monitoring of temperature and whisking, it can break into a grainy-looking oil + solids mess. If that happens to you, don’t worry! Try adding a few teaspoons of boiling water while whisking furiously. It should come back together, restoring all of your eggs Benedict brunch dreams.

Bearnaise = hollandaise made with a white wine vinegar, tarragon, and shallot reduction

Maltaise = hollandaise + blood orange juice & zest

Béchamel

Bechamel is my favorite of the mother sauces. It’s similar to veloute but uses a white roux (cooked just long enough to cook out the raw flour flavor) and onion pique-infused scalded milk as the liquid. “Wait,” you might be thinking, “doesn’t scalding mean burning?” Nope! To scald milk means that you bring it almost to a boil, just until there are tiny bubbles building up on the side of the pot and a film forms on top of the milk. This helps infuse the milk with the onion/bay/cloves pique that you added, plus it helps make the milk sweeter. I don’t know how it does it, but I’d swear that scalding the milk helps convert the milk sugars into a more detectable compound. For me, it’s an absolutely necessary step for a perfectly balanced final sauce.

Soubise = bechamel + onions

Mornay = bechamel + Parmesan + Gruyere