Personal Philosophy

Metaphysics

Optimistic Nihilism

Optimistic nihilism is a philosophical stance that embraces the meaninglessness of life and uses it as an opportunity to encourage individuals to create their own meaning. Unlike traditional nihilism, which views the absence of inherent meaning as a source of despair, positive nihilism sees it as an opportunity for freedom and creativity.

Philosophers like Friedrich Nietzsche and Albert Camus have laid the groundwork for this perspective, although they are often cited as proponents of a less positive outlook. Nietzsche's concept of the "übermensch" encourages individuals to create their own values and purposes in a world devoid of inherent meaning. The concept of an übermensch is often misinterpreted in itself; the term is used to describe what an individuals "best self" could be. In short, it describes a person who has determined their own values and is satisfied (Maden, 2022). Camus also shares the belief that life is meaningless, but states, "even within the limits of nihilism it is possible to find the means to proceed beyond nihilism” (Camus, 1942).

Optimistic nihilism is one of the core foundations of my personal philosophy. I believe that life does not come prepackaged with inherent meaning or purpose. Instead, it is up to each individual to find and create their own meaning. This view empowers me to take responsibility for my own life and choices, rather than relying on external sources of meaning. There is a certain comfort in the belief that nothing truly matters. From this foundation, every individual can create their own personal meaning, and forge a path unique to them.

Compatibilism

Compatibilism is a philosophical view that strikes a balance between free will and determinism. According to compatibilists, it is possible for an individual to be free in their actions even if those actions are determined by prior events and natural laws. This perspective stands in contrast to both hard determinism, which denies free will, and , which rejects determinism. As discussed in the Unit 2: Activity 4 of the course, a compatibilist worldview accepts that the universe is predetermined to some degree, but that there is also some degree of free will involved. This view allows me to maintain a sense of moral responsibility and accountability, which I find essential for a coherent ethical framework.

The oldest proponents of compatibility recognized that humans have choices to make, but are set on a certain path to make these choices. Aristotle, for example, held the belief that humans are responsible for their actions, but also felt that “our dispositions are not voluntary in the same sense that our actions are” (Singer & Eddon, 2022). In the eighteenth century, philosopher David Hume emerged as the strongest supporter of compatibilist views. His work "Of liberty and necessity" posited that the freedom of choice and the moral responsibility of humans can be reconciled with a form of determinism known as "casual determinism" (Russell, 2014).

In my personal experience, compatibilism seems like the sort of will that can exist. Determinism is too often used an excuse for poor or strange behaviours. Conversely, total free will seems unlikely, as some events seem totally unescapable. No matter what actions an individual takes, they will end up at certain points in their life. I have encountered several of these times in life, where it seems any "choice" would have led to one certain point in time. There is room to change and shift the journey to and the final results of these certain points. I believe that while our actions may be influenced by prior causes and conditions, we still possess the capacity to make choices that reflect our intentions.

Foundations

Introduction to Philosophy

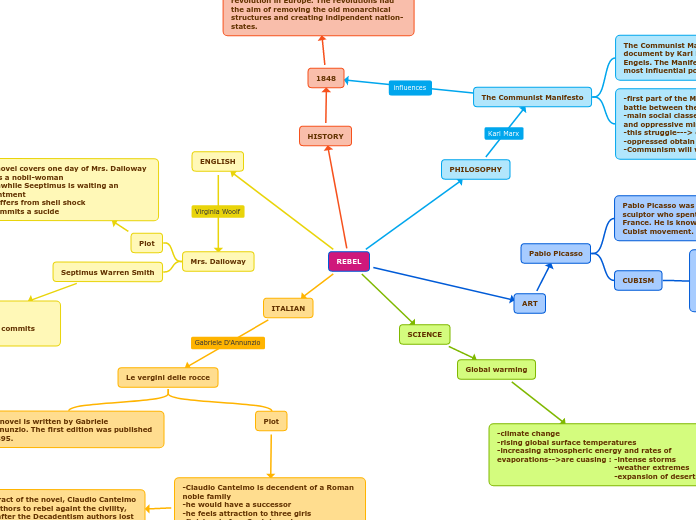

Taking my first formal philosophy course was a transformative experience, as the course provided a comprehensive overview of the major areas of philosophy; topics included metaphysics, ethics, political philosophy, and science. Each section introduced me to new ways of thinking and challenged my preconceived notions about the world. Unit 1 provided an excellent groundwork to my shifting personal philosophy; it was both informative and relatable, serving as a bridge from regular schooling to a more abstract, subjective topic like philosophy. Learning about logical fallacies and the philosophy timeline was the first step towards thinking in a more philosophical sense.

Background

Philosophy has always intrigued humanity, with most people considering philosophical questions whether they realize it or not. Despite my limited formal exposure to philosophical study prior to the course, my encounters with philosophical ideas profoundly influenced my thinking and worldview. Growing up, I was always curious about the "big questions" of life—Why are we here? What is the nature of reality? How should we live? The HZT4U course was a natural choice, as it finally gave me an opportunity to truly explore these questions.

Aesthetics

Wu Wei

Wu Wei is a central concept in Daoist philosophy, is translated into English as "non action." It signifies a way of being that aligns with the natural flow of the universe, promoting actions that are spontaneous, harmonious, and unforced. The principle, advocates for living in accordance with the Dao, the fundamental essence that underlies and unites all things in the universe. Wu Wei is a microcosm of the larger philosophy of Daoism; living in harmony with the universe and maintaining a balance with energy inside it.

The earliest and most profound articulation of Wu Wei is found in the Dao De Jing, a classical text attributed to ancient Chinese philosopher Laozi. Written around the 6th century BCE, the Dao De Jing explores the nature of the Dao, the fundamental principle that defines the universe. Laozi describes Wu Wei as the practice of aligning oneself with the Dao, acting in harmony with the natural world, and avoiding unnecessary effort or force. According to Laozi, by practicing Wu Wei, one achieves true balance and tranquility (Stefon, 2019). Today, the concept of Wu Wei continues to be relevant. It provides a counterpoint to the high-stress, goal-oriented mindset prevalent in modern societies, and encourages individuals to find peace through alignment with the natural flow of life.

My interpretation of Wu Wei aligns with my personal philosophy of seeking balance and harmony in life. The concept resonates with me as it emphasizes the importance of letting go of unnecessary effort and control, allowing things to unfold naturally. This perspective encourages a more relaxed and mindful approach to life, where actions are performed with ease and grace, rather than force and struggle. There is beauty in things that take time, which is a difficult lesson to learn. Realizing this is a key step in life, so the teachings of Wu Wei are quite valuable in that sense. An example of beauty taking time can be seen in a tree, located in my backyard. Planted as a sapling when I was quite young, the young tree has sprouted into a beautiful, sturdy maple. Its changing leaf colours each fall serve as another reminder of the importance of time's passage; Wu Wei's "course of the universe" is tremendously beautiful, so watching is all we can do.

Rasa

Rasa is a fundamental concept in Indian aesthetics. It refers to the emotional essence or "flavor" that resonates with the audience during the consumption of art. Rasa theory explores how different emotions are evoked and experienced through various forms of artistic expression, including dance, music, and drama. In Indian philosophy, it is considered the essential element of aesthetic quality, and cannot be quantified (Thampi, 1965).

Rasa is attributed to an ancient, extremely influential sage and priest named Bharata. He believed that humans had the capacity to feel nine emotions: delight, laughter, sorrow, anger, energy, fear, disgust, heroism, and astonishment. These nine emotions were represented by the various forms of Rasas, which combined to form the total aesthetic experience of human life. His initial theories were refined, with Indian philosopher Abhinavagupta, who applied the theories of Bharata to contemporary pieces of art like theatre and poetry. It is a popular belief that tasting Rasa is a reward for good deeds in a previous life (Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, 2019).

Rasa resonates deeply with my appreciation for art and its ability to evoke profound emotional responses. The concept of Rasa enhances my understanding of aesthetic experiences, as it offers a structure to analyze and appreciate the emotional impact of art. I often find that film and music elicit the greatest emotional response. For example, the deep emotional connections of Rasa were touched by the Stanley Kubrick film Barry Lyndon, a period piece with incredibly beautiful cinematography and score. The film evoked great amounts of emotion in me, and I could not describe the depth of the artistic piece. This, I feel, is the perfect representation of Rasa.

Ethics

Altruism

Altruism is the ethical belief that the well being of others should be treated in a higher regard than the well being of oneself. Explored several times throughout the HZT4U course, altruism is rooted in empathy and compassion, standing in contrast to selfishness and egoism. Its principles highlight the importance of assisting and supporting others purely for their benefit, rather than for selfish or personal gain. Altruists aim to prioritize the needs of others as their primary goal, achieving success through selfless acts.

Philosophers like Immanuel Kant argued for a duty-based ethics that included the principle of treating others as ends in themselves, rather than means to an end (Johnson & Cureton, 2022). This focuses on treating other people with dignity and respect, valuing them as individuals instead of using them for personal gain. Kant’s principle implies that ethical actions involve respecting and valuing others as ends in themselves. This requires considering how our actions affect others and ensuring that they are treated with dignity and fairness. It promotes a sense of justice and reciprocity in relationships, where individuals are not exploited or used for ulterior motives. From an altruist perspective, others should always be treated with respect and valued.

Personally, I believe that altruism centers on the belief that we have a moral responsibility to try to aid in the well being of other people, regardless of personal gain or recognition. I find altruism appealing because it creates a real sense of connectedness and mutual support within communities. Prioritizing the needs and interests of others with altruist philosophies promotes empathy. These factors can contribute to a more compassionate society. The phrase, "treat others as you wish to be treated," comes to mind when discussing altruism, as it is quite simply when taken at that level. In my life, I strive to give back, as it helping my peers in any way is incredibly important to me. If all members of society acted with the best interest of their neighbour in mind, humanity would be much better (although this is an unrealistic goal.

Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism is an ethical theory that promotes actions that maximize happiness and well-being for the greatest number of people. It falls under the branch of normative ethics. Rooted in the principle of "the greatest happiness for the greatest number," utilitarianism evaluates the moral worth of actions based on their consequences (Persky, 2016). It provides a contrast to deontological ethics and egoism.

Utilitarian ethics are closely associated with philosophers Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, who both made significant contributions to their development. Bentham introduced the idea of quantifying happiness through the "hedonistic value theory," suggesting that the right action is the one that produces the most pleasure and the least pain. Mill refined utilitarianism by distinguishing between higher and lower pleasures, arguing that intellectual and moral pleasures are superior to physical pleasures. These contributions shaped utilitarian thought, leading to countless variations (Duignan & West, 2024).

My belief in utilitarianism aligns with my broader ethical views on justice and fairness. Utilitarian principles can promote a more equitable distribution of resources and opportunities, as they encourage humanity to consider the well being of all individuals. One of the key reasons I am drawn to utilitarianism is its emphasis on the collective good. The many complex and often conflicting interests of the world make decisions increasingly difficult, but utilitarianism provides a clear guideline for evaluating actions based on their overall benefit to society. For instance, when faced with a difficult ethical dilemma like the trolley problems explored in class, I find it helpful to consider which option would result in the greatest net happiness or least harm for those affected.