O debate é

anterior a Weber

positivismo advoga

explanation

controle e

previsibilidade

características

universais das

humanidades

livre de

valores

value

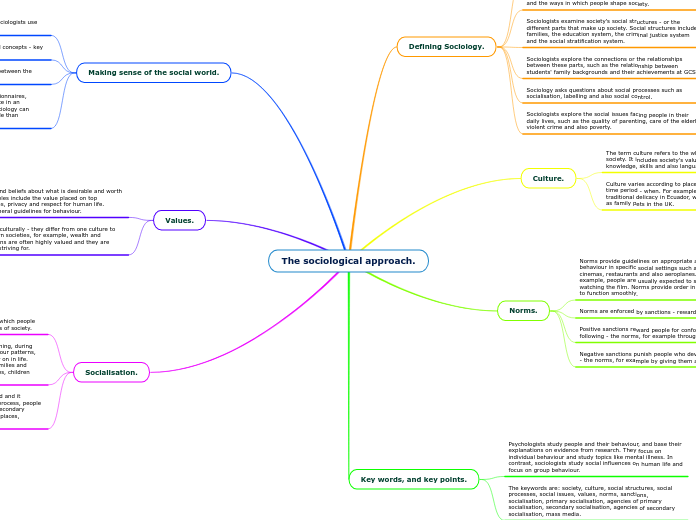

A word with several quite different meanings: in statistical analysis of quantitative data-sets, the value is the score or figure observed on a particular variable for a particular case, or in specific circumstances, that is, it is a quantified amount. In economics the labour theory of value states that commodities are exchanged according to the amount of labour embodied in them, except in the Marxian theory of exploitation, which states that employers extract a surplus and hold wages down by creating a reserve army of labour. In attitude research, values are ideas held by people about ethical behaviour or appropriate behaviour, what is right or wrong, desirable or despicable. In the same vein, philosophers treat values as part of ethics, aesthetics, and political philosophy.

Regarding values as a type of social data, distinctions are often drawn between values, which are strong, semi-permanent, underlying, and sometimes inexplicit dispositions; and attitudes, which are shallow, weakly held, and highly variable views and opinions. Societies can usually tolerate highly diverse attitudes, whereas they require some degree of homogeneity and consistency in the values held by people, providing a common fund of shared values which shape social and political consensus. It is usually held that the sociological theories of normative functionalists (or consensus theorists) in general, and of Talcott Parsons in particular, over-emphasize the importance of shared values in maintaining social order.

More generally, all sociology is concerned with value issues, and many of the classical writers—most notably Éile Durkheim and Max Weber—discussed the role of values in social research at some length. At this more philosophical level, the issues for sociology would seem to be twofold. First, since society itself is partially constituted through values, the study of sociology is in part the study of values. Second, since sociologists are themselves members of a society and presumably hold values (religious, political, and so forth), sociological work may become embroiled in matters of value—or even (as Marxists might put it) matters of ideology. Indeed, some have argued that, for this reason, sociologists may be incapable of the value-neutrality expected of scientists more generally.

These sorts of epistemological debates about the role of values in social science can impinge on sociological work at three stages: first, in the decision to study a particular topic such as religion or homosexuality, where issues of value-relevance are raised; second, in the actual execution of a study, where the issues of bias, value neutrality, and objectivity are raised; and, finally, in the consequences of particular theories or research for society, where the issue of ‘value effects’ is raised. In practice, most sociologists accept that such sharp distinctions cannot readily be made, and the various value issues overlap.

One of the defining characteristics of philosophical positivism is that it takes the sciences (including social sciences) to be value-neutral or value-free—the expectation being that scientists will (or at least should) eliminate all biases and preferences at each stage of their studies. Value-neutrality is therefore indispensable for a scientific sociology. Similarly, sociology is considered to have a purely technical character, reporting findings that carry no logically given implications for policy or the pursuit of particular values. In marked contrast, Marxists argue that every stage of sociological analysis is riddled with political and moral assumptions and consequences, such that sociology is itself irredeemably an ideological enterprise. However, most sociologists hold positions somewhere between these extremes, arguing (for example) that although the choice of research areas must raise matters of value, the execution of a study should be as impartial as possible, and the findings presented neutrally, at which point the way such findings are put to use by others will again raise value (that is, policy) issues. A frequently encountered pragmatic solution to the apparently intractable epistemological issues raised by the question of values is the suggestion that sociology is always bound up with ethics, politics, and values, and since it cannot purge itself of them, sociologists should make the underlying debates explicit.

Some of the classic value debates involved such notables as C. Wright Mills, Howard S. Becker, Alvin Gouldner, George Lundberg, Robert Lynd, and Gunnar Myrdal (most of whose works are treated elsewhere in this dictionary). However, the major methodological statement is still to be found in the essays contained in Max Weber's The Methodology of the Social Sciences (1904–18), especially those sections where he discusses the philosophical basis of ‘value-relevance’ as a principle of concept formation. Here, Weber argues (following the epistemology of Heinrich Rickert (see Geisteswissenschaften and Naturwissenschaften)) that reality is infinitely complex and conceptually inexhaustible; that the natural and social sciences typically use generalizing and individualizing modes of concept formation; and that the objects of the latter are distinguished by being imbued with meaning and values. Value-relevance, for Weber, governs the selection of facts in the social and historical sciences by clarifying the value inherent in a situation or phenomenon under analysis. Of course, there are always several possible plausible interpretations of the values underlying cultural phenomena, and consequently several different points of view from which one might conceptualize the phenomenon (or ‘historical individual’) to be explained. However, once a historical individual is constructed for a particular inquiry, ‘objectively one-sided’ social scientific knowledge becomes possible through the discovery of causal relationships between the value-relevant description of the object of enquiry and antecedent historical factors, because the formation of these relationships is governed by the established rules of scientific procedure. If the particular value-standpoint according to which the object of enquiry has been conceptualized does not facilitate an explanation of the phenomenon which is both meaningfully and causally adequate, then there may be other values inherent in that phenomenon which permit a more satisfactory explanation to be constructed. This complex argument is described in full in Thomas Burger's Max Weber's Theory of Concept Formation (1976). See also Normative Theory.

métodos das

ciências naturais

Crotty - Capítulo 4 - Interpretivism: for and against culture

Main topic

Raízes do

interpretativismo

Neokantianos

Heinrich

Rickert

(1863 - 1936)

Métodos

individualizantes

Métodos

generalizantes

- naturais

Wilhelm

Windelband

(1848 - 1915)

Distinção

lógica

entre

social e

natural

Subtopic

Assuntos

humanos

casos individuais

(idios)

nnnIidiográfico

Naturais

Consistências,

regularidades,

a 'lei' (nomos)

Nomotético

Wilhelm

Dilthey

(1833 - 1911)

Realidade social

# realidade natural

Métodos

diferentes

Max Weber

(1824 - 1920)

métodos

diferentes

(mais quali)

Compreensão

(Verstehen) ao

invés de explicação

(erklären) das

naturais

introdução

interpretação do

mundo social

situada

historicamente

derivada da

cultura

entendimento e

explanação da realidade

humana e social

contrapõe-se ao

positivismo