MODULE 3: Descriptive Paragraph Relating to the Changes of our Project

For Module 3, we decided to add an extension to our previously established curriculum designs by including the planning, instruction, and assessment aspects of each curriculum design. Using the readings as a baseline, as well as adding information from our own personal experiences, we described what the planning, instruction, and assessment would look like within each curriculum design (curriculum designs included subject-matter design, learner-centred design and problem-based design). Breaking down each curriculum design into the planning, instruction, and assessment processes helped us to further synthesize our understandings of each curriculum design through the process of comparing and contrasting details from each reading. Additionally, this module afforded us the opportunity to draw parallels between the curriculum designs and our personal practices in teaching through discussions with our partners.

References:

Castellon, A. (2017). A call to personal research: Indigenizing your curriculum. The Canadian Journal for Teacher Research: Teachers leading transformation.

Hayes, D. (2003) Making learning an effect of schooling: aligning curriculum, assessment and pedagogy, Discourse: studies in the cultural politics of education, 24(2), 225-245

Jamieson, H. (2021). PME 810: Module 1 Conceptions of Curriculum Padlet Response. https://padlet.com/hjjamieson/lai40ppmhtdramnv

McMillan, J. H. (2014). Classroom assessment: Principles and practice for effective standards-based instruction (6th ed., pp. 1-20, 57-64,74-88). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Ornstein, A. C. (1990/1991). Philosophy as a basis for curriculum decisions. The High School Journal, 74, 102-109.

Ornstein, A. C., & Hunkins, F. P. (2013). Curriculum: Foundations, principles, and issues (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson. Read Chapter 6, pp. 149-173.

Ralston, J.S. (2018): Where is the Standardized Testing Trend Taking Us?

http://vimeo.com/28412154

Schiro, M. S. (2013). Introduction to the curriculum ideologies. In M.S. Schiro, Curriculum theory: Conflicting visions and enduring concerns (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. pp. 1-13.

Shepard, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher, 29(7), 4-14. doi:10.3102/0013189X029007004

Sir Ken Robinson (2013). How to Escape Education’s Death Valley.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wX78iKhInsc

Sowell, E. J. (2005). Curriculum: An integrative introduction (3rd ed., pp. 52-54, 55-61, 81-85,103-106). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Descriptive Paragraph of Our Thinking Behind the Mind Map:

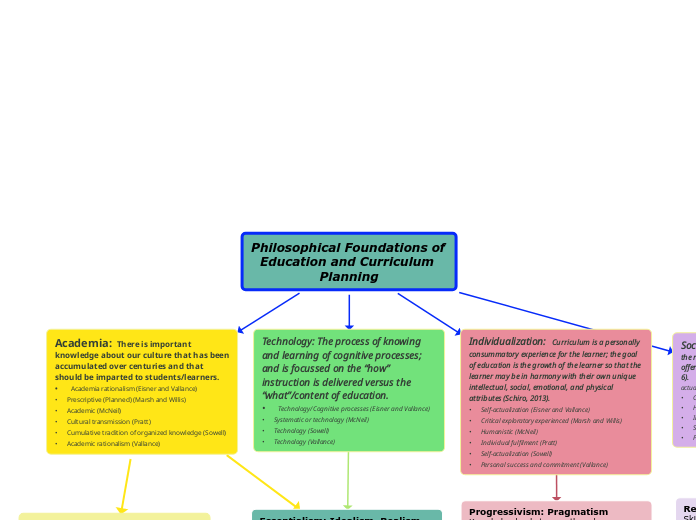

We decided to present our work using a ‘mind map’ to outline the varying connections between the conceptions of curriculum (learned about in Module 1), philosophical foundations of curriculum and then curricular designs. At the top of our mind map are the four main conceptions of curriculum, being ‘Academia, Technology, Individualization and Society’ Conceptions of curriculum, with brief explanations of these conceptions. From there, we outlined how the philosophies fit to each conception, and drew connecting lines between philosophies and conceptions that had similar ideas. Note that essentialism draws parallels to both Academia and Technology. Finally, we connected the curricular design theories to philosophies that best fit. Many lines are interconnected, meaning the design theories fit with more than one philosophy. Starting with the four conceptions of curriculum really helped to break down the connections between curricular conceptions, philosophy and curricular designs. Finally, at the bottom we added considerations of content organization and components of design, as these are integral parts of the curricular design process.

Components of Design

Conceptual Frameworks

Sources of Curriculum Design

CONSIDERATIONS OF CONTENT ORGANIZATION

SCOPE; all of the types of educational activities to engage students in learning (Ornstein, 2013, p. 156)

SEQUENCE; curricularists decide how to content and experiences can build on what came before (Ornstein, 2013, p. 156)

CONTINUITY; skills continue to be learned overtime, year after year, revisited and built upon (Ornstein, 2013, p. 157).

INTEGRATION; links all of the curriculum pieces so that students view knowledge as unified. Horizontal relationships amongst topics occur (Ornstein, 2013, p. 158).

ARTICULATION; sequencing of content from one grade to the next and content difficulty across grade levels (Ornstein, 2013, p. 158).

BALANCE; educators strive to give appropriate weight to each aspect of design. "Students acquire and use knowledge in ways that advance their personal, social and intellectual goals." (Ornstein, 2013, p. 159)

Curriculum Designs

• Focus is on real-life problems of individuals and society

• Intended to reinforce cultural traditions and address unmet needs of the community and society

• Based on social issues

• Places the individual within the context of the social setting (with the difference from learner-centered design in that some pre-planning is done prior to students’ arrival)

Social-Cultural-Based Design

Problem-Centered Design

Planning:

• Backward mapping

• 21st Century learning

• Establish a connection with the local Indigenous community to promote the sharing of Indigenous Elders’ knowledge

• Use of Learning Circles to focus on noticing problems, disparities, and injustices

• Follow, for example, BC Ministry of Education's Indigenization of the curriculum through new constructs and opportunities for leadership, practices, content, and vision.

• Plan for student learning and understanding through multiple ways of knowing i.e., orally, visually, etc.

• Plan to be culturally responsive using rich, Indigenous content that appropriately represents and reflects Indigenous peoples in the curriculum

• Resource selection is of primary importance-- again the use of Indigenous ways of knowing and ensuring the use of authentic, First Peoples texts that are historically accurate

• Restorative principles: teach decolonization and TRC principles without shaming or blaming, but instilling a sense of responsibility in all

• Teacher to participate in PLC’s that include Elders and Networks of Inquiry

Instruction:

• Experiential learning for selecting instruction that privileges place-based education i.e., stories, histories; education takes place outdoors and is connected to the land

• Employs inquiry-based learning to explore problems, disparities, and injustices

o Halbert & Kaser’s (2013) Spirals of Inquiry approach is used to ensure that each learner has a genuine opportunity to develop a deep understanding and respectful listening skills through Indigenous ways of knowing

• Acknowledgement and discussion of intergenerational trauma through Learning Circles, which encourages the development of deep and respectful listening; and gives voice to both individuals and communities

• Critical thinking skills to promote independent action and critical analysis of Intelligent resistance (resources/ media/ bias) (Brookfield, 2012; 2013).

• Cultural responsiveness – today’s Elder’s experiences of the 60’s Scoop, and intergenerational trauma

• Restorative practises used to increase awareness and foster relationships with Indigenous and Non-Indigenous peoples

• Holistic learning environments that emphasize contextualized learning connected to each persons’ life and identity, i.e., community, land, etc.,

Assessment:

• Use of reflections, journal responses

• Contextualized problem-solving opportunities (meaningful, applicable to real-life situations)

• Personalized feedback

• Allows for multiple ‘ways of knowing’ and expressing understandings

• Formative and summative

• Open-ended performance tasks

• Assessment of, for and as learning (McMillan, 2014)

Curriculum Designs

• Students are the program focus (Ornstein, 2013)

• Teachers stress the “whole child” approach (Ornstein, 2013)

• Learner-centered designs essentially stresses two of the three big ideas regarding thinking about education: socialization, and Rousseau’s developmental ideas (Ornstein, 2013, p. 165)

• Knowledge is an outgrowth of personal experience (Ornstein, 2013)

• Shift from subject-matters to students needs and interests (Ornstein, 2013)

Learner-Based Design

Planning:

• Backward mapping – planning with the end in mind, and then developing the instructional lessons, activities, and/or approaches to reach the end learning intentions

• 21st Century learning

• Teacher as a facilitator

• Planning is based on what students want to learn (Power of student voice to enhance teacher practice)

• Flexible and responsive planning/instruction; adapting and changing plans based on student needs

• Student needs come before curriculum needs (look at the students first),

Instruction:

• Teacher as facilitator, provides foundational basics to launch learning

• Provocations used to stimulate learning

• Teacher and students are co-creators,

• Student voice and choice emphasized

• Inquiry-based / projects learning opportunities

• Collaboration approach to learning, learning is dynamic

• Instruction is minimal but allows for sense of student responsibility, inquiry, conflict resolution, technology-orientation, problem-solving, and student leadership in learner-centered designs (Ursula Franklin Academy)

• Inquiry-based projects, a lot of assessment is not through traditional measures, but rather through oral language and formative assessments as teachers watch the learning unfold (EdCan Network Video)

Assessment:

• Assessment for and as learning

• Peer and Self-Assessments

• Feedback and conferring

• Use of reflections, journal responses

• Formative and summative assessments

• Personalized feedback, and rubrics given the inquiry-based learning approach

• Teacher’s need for flexibility and reflexiveness (Hayes, 2003)

• Reflection on classroom practices (Hayes, 2003)

• Increased use of technology in learner-centered approaches to assessment (McMillan, 2014, p. 8)

Learner-Centered Design

Curriculum Designs

• By far the most popular and widely used

• Knowledge and content are well accepted as integral parts of the curriculum

• History of academic rationalism; materials used created for school use

• Have the most classifications

• In our culture, content is central to schooling; therefore, we have many concepts to interpret our diverse organizations

Subject-Centered Design

Subject-Matter Design

Planning:

• Forward mapping

1. texts,

2. existing linear lesson plans

3. grade level structured

• 20th Century thinking

• Standards-based ideology is the basis of the planning process

• Formal educational knowledge - three message systems:

1. Curriculum defined as what counts as valid knowledge

2. Pedagogy as what counts as valid transmission

3. Assessment as what counts as valid realization of the imparted knowledge

John Ralston Paul video:

• rising power of utilitarianism

• Proficiencies and deliverables

• testing culture, notion to keep everyone on track

Sir Ken Robinson video:

• Standards discipline is necessary but not efficient for good educational system

Instruction:

• Teacher-led, efficient instruction

• Direct, explicit instruction

• Learning objectives

• Teaching to the test

• Rubrics provided as a learning tool to students to guide their learning

• Advocates of standards-based reforms hope that by outlining what students should know and be able to do will overcome problems down the road (Hayes, 2003, p. 228)

• Instruction is “teacher-directed,” minimal student voice or choice

Assessment:

• Standards-based assessments

• End of Unit testing, marks counted in summative assessment

• Tests (curriculum alignment) did not necessarily match pedagogical goals (Hayes, 2003, p. 229)

• High-stakes testing

• Assessing meaningful learning through high-quality measures tied to standards and supplemented by local indicators of learning

• Assessments used to inform curriculum reform and guide investments into better teacher preparation, improved learning conditions

• Curriculum pedagogy and assessment is monitored and negotiated to ensure:

1. Shared understanding

2. Common language to discuss the shared understandings; and

3. mechanisms for aligning their purposes

• Minimized sense of democracy or student flexibility in showcasing of learning (John Ralston video)

Philosophical Foundations of Education and Curriculum Planning

Society: the purpose of education is to facilitate the reconstruction of a new, more just society that offers maximum satisfaction for all (Schiro, 2013, p. 6). • Self-actualization (Eisner and Vallance)

• Critical exploratory experienced (Marsh and Willis)

• Humanistic (McNeil)

• Individual fulfilment (Pratt)

• Self-actualization (Sowell)

• Personal success and commitment (Vallance)

Reconstructionism: Pragmaticism Skills and subjects needed to identify and ameliorate problems of society; learning is active and concerned with contemporary and future society. Teacher helps students become of aware of societal problems (Ornstein, 1991)

Reconstructionist Design - "curriculum should foster social action aimed at reconstructing society" (Ornstein, 2013, p. 171).

Life-situations Design - curriculum designed to deal with societal aspects, students see the relevance of content if organized around community life (Ornstein, 2013)

Radical Design - "School curricular designs, school curricula, and the administration of schools' programs are planned and manipulated to reflect and address the desires of those in power." (Ornstein, 2013, p. 167)

Individualization: Curriculum is a personally consummatory experience for the learner; the goal of education is the growth of the learner so that the learner may be in harmony with their own unique intellectual, social, emotional, and physical attributes (Schiro, 2013). • Self-actualization (Eisner and Vallance)

• Critical exploratory experienced (Marsh and Willis)

• Humanistic (McNeil)

• Individual fulfilment (Pratt)

• Self-actualization (Sowell)

• Personal success and commitment (Vallance)

Progressivism: Pragmatism Knowledge leads to growth and development; a living-learning process; focus on active and interesting learning. Teacher guides problem-solving, inquiry and activities based on student interest (Ornstein, 1991)

Process Design - procedures and processes in which students obtain knowledge (ex. students studying biology learn biological methods). (Ornstein, 2013)

Child-Centered Design - design of learning should be based on students lives, needs and interests. Teaching suits a child's developmental level (Ornstein, 2013)

Experience-Centered Design - children's needs cannot be anticipated, curriculum framework cannot be planned for all children, students design own learning (Ornstein, 2013)

Correlation Design - separate subjects, disciplines linked but separate identities maintained (Ornstein, 2013)

Broad-fields Design - interdisciplinary design, melding two or more subjects together (Ornstein, 2013)

Humanistic Design - experiences, interests, needs of person and group (Ornstein, 2013)

Technology: The process of knowing and learning of cognitive processes; and is focussed on the “how” instruction is delivered versus the “what”/content of education.

• Technology/Cognitive processes (Eisner and Vallance)

• Systematic or technology (McNeil)

• Technology (Sowell)

• Technology (Vallance)

Essentialism: Idealism, Realism Essential skills and academic subjects; mastery of concepts and principles of subject matter. Promotes the intellectual growth of the person, teacher promotes traditional values (Ornstein, 1991)

Academia: There is important knowledge about our culture that has been accumulated over centuries and that should be imparted to students/learners. • Academia rationalism (Eisner and Vallance)

• Prescriptive (Planned) (Marsh and Willis)

• Academic (McNeil)

• Cultural transmission (Pratt)

• Cumulative tradition of organized knowledge (Sowell)

• Academic rationalism (Vallance)

Perrenialism: Realism Focus on past and permanent studies; mastery of facts and timeless knowledge, explicit teaching of traditional values. (Ornstein, 1991)

Subject Design - separate subjects, curriculum organized by subject and how essential knowledge has developed in various subjects (Ornstein, 2013)

Discipline Design - focuses on scholarly disciplines, students experience disciplines to comprend and conceptualize (Ornstein, 2013)