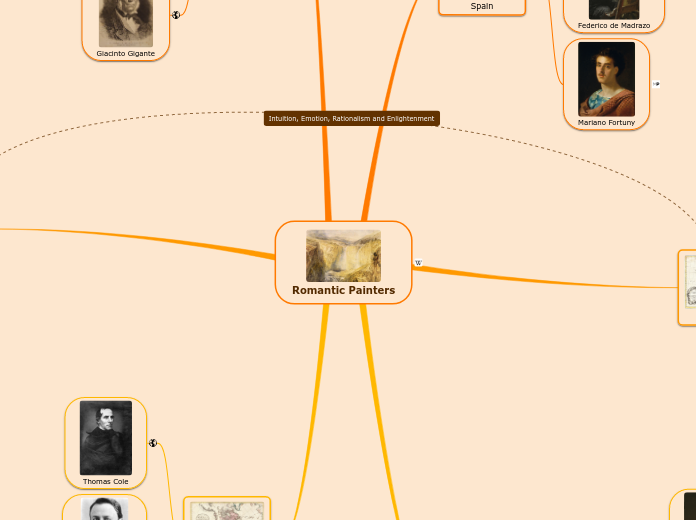

Romantic Painters

America

Like other terms describing literary movements, the term Romanticism defies simple definition for a number of reasons. It was a movement that arose gradually, evolved in many ways from where it began, went through so many phases and was practiced by so many disparate writers that any simple definition is "slippery" at best. In addition, the terms we use to describe literary movements are really terms that are much broader and vaster, reflecting large scale thinking in the arts, in general, philosophy, religion, politics, etc.

American Romanticism, like other literary movements, developed on the heels of romantic movements in Europe. Its beginnings can be traced back to the eighteenth century there. In America, it dominated the literary scene from around 1820 to the end of the Civil War and the rise of Realism. It arose as a reaction to the formal orthodoxy and Neoclassicism of the preceding period. It is marked by a freedom from the authority, forms, and conventions typical in Neoclassical literature. It replaced the neoclassic emphasis on reason with its own emphasis on the imagination and emotions, and the neoclassic emphasis on authority with an emphasis on individuality, which places the individual at the center of all life. See the list of themes and elements below for a clearer description of the elements of Romanticism.

Washington Allston

Albert Bierstadt

Thomas Cole

Germany

Two key trends dominated Romantic art: early Romantic painting originated in the Protestant North; South Germany was the home of the Lukasbrüder (Brotherhood of St Luke), who later became known as the Nazarenes (alluding to primitive Christians). The rise in popularity of and demand for Realist and Impressionist works of art and literature limited Romanticism to painting on a local level.

3. Dominant Characteristics

Older romantics, such as the Schlegel brothers and Novalis, tended toward “Sturm und Drang”, which sought depth and profound emotion. For them, Romanticism was not a reaction against Classicism; nor did it ignore Classicism’s achievements – rather, it supplemented and amplified them, placing stronger emphasis on the realm of the unconscious. Fritz Strich defined Classicism as innately calm; it insisted upon completeness and perfection. Romanticism, contrariwise, was intrinsically restless and indefinite; longing had neither aim nor limit. Subsequently, borderlines between the arts became obscured, and art, literature and music merged. Creative minds of the time saw tones, colours and words all as different forms of the same language.

Joseph Anton Koch

Phillip Otto Runge

Caspar David Friedrich

Italy

In the decades following the French Revolution and Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo (1815) a new movement called Romanticism began to flourish in France. If you read about Romanticism in general, you will find that it was a pan-European movement that had its roots in England in the mid-eighteenth century. Initially associated with literature and music, it was in part a response to the rationality of the Enlightenment and the transformation of everyday life brought about by the Industrial Revolution. Like most forms of Romantic art, nineteenth-century French Romanticism defies easy definitions. Artists explored diverse subjects and worked in varied styles so there is no single form of French Romanticism.

Intimacy, spirituality, color, yearning for the infinite

Even when Charles Baudelaire wrote about French Romanticism in the middle of the nineteenth century, he found it difficult to concretely define. Writing in his Salon of 1846, he affirmed that “romanticism lies neither in the subjects that an artist chooses nor in his exact copying of truth, but in the way he feels…. Romanticism and modern art are one and the same thing, in other words: intimacy, spirituality, color, yearning for the infinite, expressed by all the means the arts possess.”

Giacinto Gigante

Antonio Fontanesi

Francesco Hayez

Britain

In England, as in Germany, the first Romantic stirrings were to be witnessed in nature poetry among other genres, such as that of James Thomson, or in the nocturnal songs of Edward Young. This return to nature, this emphasis on the power of the individual, must be seen as a reaction to the mechanisation and depersonalisation brought about by the Industrial Revolution in England. This had brought with it a rift between capital and labour, between employer and employee, thus establishing a new hierarchical social order. Commercialism and urbanisation had led to unfree ways of life; and these in turn provoked the artist and the writer to express their subjective, emotive life and make the spectator or reader partake in their own existential struggle. Individualism became a means to retain mental and emotional independence. In literature and art the conflict between the "I" and the world, between the individual and the state, was explored. The aim everywhere was to express inner rather than outer realities.

In painting this is perhaps most directly expressed in portraiture. Social rank and status were no longer important. Where the artist had previously been commissioned to portray patrons in official costume or emphasise the importance of the sitter, the accent now fell on the uniqueness of' the individual. The self-portraits of artists, such as Palmer (c 1826) in England, and Friedrich in Germany, confront the spectators with a gravity and intimacy that were largely lacking in 18th century portraits. In Palmer's Self-portrait of 1826 an emotional sincerity comes across in a direct and spontaneous manner. A sense of mystery and spirituality characterises the portrait. Palmer used the features of Christ to express personal suffering. Portraits of children, especially those by Runge in Germany, are characteristic of the period because they reflect the innocence, sincerity and spontaneity which the Romantics considered to be essential to reassessment of the self. To the Romantic artist the child also symbolised an unspoiled primeval mystery; and for Runge children became a symbolic reflection of raw, pure energy in nature, as seen in his Portrait of his Parents (1806).

Henry Fuseli

Constable

Turner

France

France slipped from the exalted ideals of the

Revolution

towards the Napoleonic imperialism. The same happened in art which slid from Neoclassicism towards Romanticism. The Napoleonic wars were the first to use the patriotism of the masses as a military factor. Napoleon's army was the first national army, unlike earlier mercenary armies contracted by the king. Napoleon's soldiers fought for their country and not for the money of a foreign king. This led war to be understood differently and the ardour of the combaters was different as was the sense of death. For the first time the chief was secondary to the figure of the anonymous hero. The subject matter of the horrors of war had made itself felt during the pre-Romantic period which was still dominated be classicist aesthetic tendencies. Gérard, Gros, Boisdenier, Meissonier and Proud'hon were artists who started out in the neoclassical academies but then tinged their images with sentiment and humanity. They often followed the literary innovations of the early European romantics such as Tolstoy and Stendhal, who also wrote about the effects of war. However, Romanticism was not fully developed until 1830. The play "Hernani" by Victor Hugo was premiered and the theatre became the scene of a pitched battle between classics and romantics. In the same year Prosper Mérimée visited Spain and composed his opera "Carmen". In the face of this explosion of feeling the pictorial scene continued to bow down to Ingres and Academicism. Géricault, with his agitated personal life, was responsible for shaking up young artists and introduced them to a new aesthetic. Géricault is the first prototype of the romantic painter, who died young in a mental asylum where he made some extraordinary sketches of other mentally ill patients. He was the godfather of the romantic generation, especially of Delacroix, as both of them pay homage to the other in their paintings (the most famous case is Géricault's Raft of the Medusa and Delacroix's Barque of Dante in which both artists copy and portray each other). The main aspects of French Romanticism were the preservation of the classical canon for the figures but a greater freedom in the use of light and colour, the employment of twisted movement creating more aggressive compositions. The combination of classicism and sentiment relates French Romanticism aesthetically to German and

Spanish Romanticism

respectively. At the same time a landscape school that as similar to Spanish eclecticism developed with its most notable members being Chassériau and Meissonier. They laid the foundations for the landscape painting of the

Barbizon School

and of Corot, the most immediate precursors of

Impressionism

.

Ingres

Theodore Gericault

Eugene Delacroix

Spain

Romanticism was many things at the same time. On one hand it was a philosophical movement (closer to German Romanticisim); a popular sentiment (similar to the feelings unleashed during

French Romanticism

immediately after the

French Revolution

); a literary trend (as can be observed in English Romanticism); and an artistic style. From country to country it varied greatly. The appearance of Romanticism in Spain was determined by foreign and national factors. Among the foreign factors was the rise of the middle class with the importance they gave to the individual and subjective, a result of the fact that it was a self-made class in contrast to the control of the aristocracy. The middle classes had their own ideology, Liberalism, as well as a particular political sentiment, Nationalism. Romanticism is therefore generally defined as a bourgeois art, dependent on the individual, subjective, and directed at national values which were found in the past. We will now consider the national factors that made up Spanish Romanticism. In Spain there was a popular Romanticism that was more a sentiment that an ideological system. This was determined by the Napoleonic invasion of Spain. The

Spanish War of Independence

was the first romantic war in history, carried out by the people who formed spontaneous guerrilla groups to drive out the foreign invaders. Interestingly, this desire to defend one's country against foreign intruders was an idea inspired by the enemy: France, the

Enlightenment

and

Napoleon

himself, who initially used this principle to boost his own strength but by transmitting it to the conquered territories laid the future foundations of rebellion. This popular Romanticism took place early on and was idealistic, liberal and produced the first Spanish Constitution passed in Cadiz in 1812. The best portraitist of the period and its intentions was

Goya

, the first Spanish Romantic painter. On the other hand there was also a historic romanticism that was a defining intellectual movement of the second third of the 19th century. It was directed at exalting national values which were to be sought in the past, specifically in the

Spanish Golden Age

, the zenith of Spanish culture and genius. To these, the values taken from

Spanish Neoclassicism

were added, which in turn had taken directly from the French Enlightenment and included the importance of education and popular culture. Finally, in historic romanticism there was an echo of European Liberalism, which at that time represented the avant-garde of progress in contrast to the attempts to reconstruct the Ancien Régime, apparent in the restoration of

Ferdinand VII

to the Spanish throne after Joseph Bonaparte was expelled. Regarding painting there were three important centres for Romanticism in Spain: Andalusia, Madrid and Catalonia. In Andalusia there had long been an important commercial and cosmopolitan tradition because of its Atlantic ports. In Seville and Cadiz a large foreign colony settled, especially British diplomats and their families, which affected artistic production significantly. It produced the intimism characteristic of the English Romantic portrait. When foreign families wanted their portrait painted in Spain they did so wearing traditional Spanish costumes or with important monuments in the background such as the Giralda or the Alhambra... This influenced the rise of the picture-souvenir, which was almost mass-produced, poor-quality and dedicated to folkloric themes such as pilgrimages, bandits, gypsies and so on. The style ended up stagnating and artists with cultural interests had to migrate to Madrid as in the case of the Bécquer brothers: Gustavo Adolfo, the famous romantic poet and his brother, Valeriano, an artist. In Madrid, the second centre of Romantic painting, the predominance of the Academy set the style, such as in Gutiérrez de la Vega or Esquivel, with the official panorama being totally dominated by the figure of Federico de Madrazo. Painting in Madrid was also closely linked to literature and group portraits, depicting painters and writers who met in the houses of wealthy upper-middle class individuals for artistic gatherings, were not uncommon (for example Meeting of Poets). The only escape route from this strict establishment art was genre painting, which focused on the daily habits of the Madrilenians. Leonardo Alenza cultivated genre painting in a Goyaesque fashion, deliberately imitating his style, although with a gruesomeness and a shortage of resources that meant that there was no comparison with the Aragonese master.

Eugenio Lucas

, on the other hand, practised a more decorative genre style that was appropriate for display in a bourgeois house. Regarding landscape painting, there were also two trends, the imaginative tendency which recreated fantastic landscapes like those by Pérez Villaamil, and the documentary landscape, with a scientific intention that meant it had similarities to English

Neoclassical

landscape painting. Catalonia was the other centre of Romanticism. It was a flourishing region, full of wealthy traders and industrialists who wanted their lives and family values depicted. Here the private portrait reached a splendour that was unequalled in the rest of Spain. The Lonja School in Catalonia is also notable. It was a community experiment of a group of painters who aimed to recover the purity of drawing and subject matter in the style of the Nazarenes of German Romanticism.

Mariano Fortuny

Federico de Madrazo

Francisco De Goya