Section B, Question 4: Power, Punishment and Control- IPP's

Section B, Question 4: Power, Punishment and Control- IPP’s

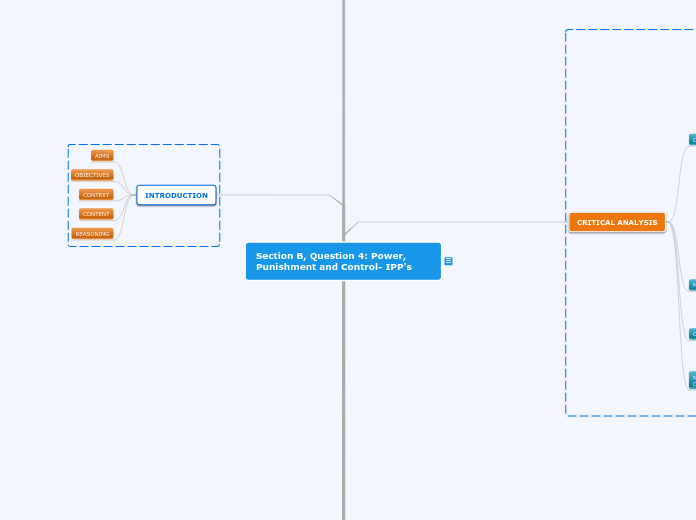

This mind map relates to Section B, Question 4: Imprisonment for Public Protection:

The focus of the question will be to explore details the new politics of law and order, that controlling less fortunate citizens has become the priority in so-called liberal, non-oppressive states. By vilifying the undeserving poor, increasing incarceration rates, imposing mandatory sentencing is more akin to Weber’s iron cage of rationality than an open democracy.

The aim is to explore:

- The process by which societies respond to deviant behaviour either informally or formally through official agents of social control.

- Imprisonment for Public Protection sentence, its introduction, application, repeal and its impact.

Main topic

CONCLUSION

RECAP

INTRODUCTION

REASONING

CONTENT

CONTEXT

OBJECTIVES

AIMS

CRITICAL EVALUATION

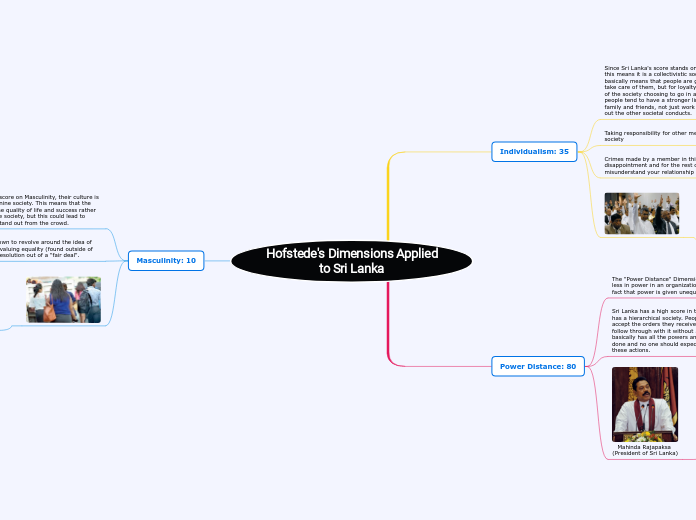

A cynical and powerful tabloid media

Assumed to represent the 'will of the people'- ratcheting up 'risk' rhetoric and orientating public debates on how the CJS manage 'Dangerous Offenders'.

What has occurred is not so much a democratising shift of power towards the public, but a reshaping of elitism in penal policymaking away from the traditional Oxbridge–Whitehall nexus.

While such secretive interventions are by definition obscured, the sustained campaign by the News of the World on the issue of sexual predators (that in part propelled the development of the IPP sentence) was all too clear to see.

A tale of continued and substantial influence on penal policymaking of a very small number of tabloid newspaper editors.

A judiciary fettered by legal formalism and deference to parliament

It’s the result of ‘illusory democratization’ (Annison, 2015: p.72).

The characterisation of the goals of incapacitation and rehabilitation as ‘contradictory’ (Annison, 2015: 41).

An 'unresolved tension’ in the assumptions underlying the IPP sentence: Ministers desired a sentence which would protect the public from those posing a significant risk but also assumed that processes were in place which would serve to rehabilitate the offender (Annison, 2015: 41).

‘Yes minister’ traditions of civil servants in the ‘Westminster model’

The dominant Westminster tradition facilitated the development of the IPP sentence, and underpinned a process in which, while being a constant reference point, the public effectively constituted ‘dummy players’.

Elites with limited access to public opinion

Warnings about limitations of extant risk assessment processes and the likely effects on prison population and resources were raised, but largely ignored.

The Government ministers’ demand for a risk-based sentence targeting ‘dangerous offenders’ meant that many dissenting and informed voices were sidelined:

CRITICAL ANALYSIS

s. 123 of the Legal Aid Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (‘LASPO’)

IPPs were repealed.

Although repealed, over 5,000 IPP prisoners remain in the prison system past their minimum term despite the Human Rights Joint Committee’s (2011) recommending the need for legislation to deal with them.

By the end of 2014- there were 5,119 still serving IPP sentences of which 71% were past tariff (Prison Reform Trust, 2014:24).

Unable to persuade the Parole Board to release them (see James, Wells and Lee v. UK (2013) 56 EHRR 399).

Criminal Justice and Immigration Act, 2008:

Loosened the structure of the 2003 Act, by means of amendments-

It gave sentencers greater discretion, particularly on whether to impose an IPP.

Gave judges the power (‘may’) but not the duty (‘must’) to impose one of the three levels of protective sentences.

Mandatory framework:

Lack of Judicial Discretion led to a large number of offenders being subjected to IPP sentences:

Led to effects on both those imprisoned and the prison service.

By the end of December, 2009, 6,034 IPP’s had been handed out with 5,828 in custody in January, 2010, of whom over 2,500 were being detained beyond their tariff (Jacobson and Hough, 2010:9).

Criminal Justice Act, 2003

Yet, within the ministerially-led policymaking process that followed:

Drawing on the concept of legitimation work:

The need to be seen as ‘responsible’ constrained relevant actors in their efforts.

Policy participants, especially parliamentarians and penal reform groups, were realistic about the extent to which such efforts were a ‘game of odds’, being heavily reliant upon ministerial (and Prime Ministerial) reshuffles and resulting government receptiveness to arguments for change under the Westminster tradition.

Penal reform groups and parliamentarians struggled to raise concerns about a ballooning prison population and the fate of IPP prisoners becoming stuck in an under-resourced system.

The voices of experts and the public were largely excluded from discussions.

Annison (2015:3) uses a framework of ‘interpretive political analysis’:

to evidence an ‘incompleteness’ of ‘governmentality gap’ in macro-level sociological account of ‘penal transformation and reconfiguration (McNeill et al., 2009: 420).

to explore how and why the potentially restraining influences appeared to have little effect on the progress of a policy that was to prove so damaging.

risk prediction capabilities were over-estimated

‘Dangerousness’ Provisions- offered a range of indeterminate sentences to replace the previous life sentence.

DESCRIPTION

DEFINING CRIME-

As we have recently witnessed, the failure to deal appropriately with law and order can be damaging to a particular government’s reputation and authority.

Much of the inflation in custody rates is a result of the number of prisoners defined as ‘serious’ and as presenting a ‘risk’ to the public- dangerous offenders were considered to be a pressing issue by the New Labour government:

There existed three central drivers for the sustained focus on a small number of violent, predatory individuals:

the salience of the dangerous offender problem was heightened by the dominant Third Way political ideology and the promotion of the ‘ontological security’ of citizens that was at its core.

policymakers considered that developments in risk assessment meant that selective incapacitation of ‘the dangerous’ was entirely feasible;

widespread recognition among politicians, policymakers, and practitioners that a perennial ‘real problem’ existed;

Ian Huntly

Roy Whiting

Such concerns have dominated law and order discourse since the early 1970’s.

But how influential is public opinion in the implementation of potential penal policies?

Formulating policies which appear to ‘protect the public’ while reducing cost.

Strong commitment successive governments have made to the use of longer sentences and increased use of custody.

Such issues highlight the difficulties facing the government when the political need to pursue policies and practices deemed by the public as legitimate conflict with economic or political imperatives.

Public opinion is a crucial pressure on the government at election time as parties try to capture floating voters.

What is seen as an appropriate response to crime and the type and level of response required often reflects:

Political Ideologies

Public Opinion

Cost