Uguale, davanti a chi?

IN WHICH WE ASK WHAT, PRECISELY, IS EQUALIZED IN ‘EGALITARIAN’ SOCIETIES?

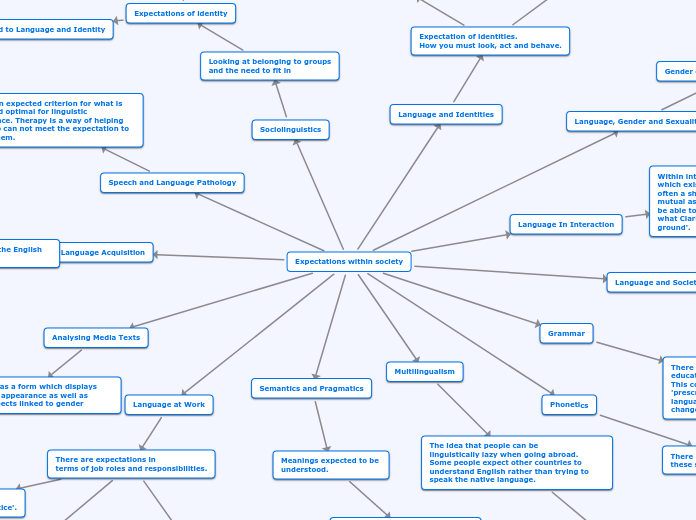

‘inequality’ is a slippery term, so slippery, in fact, that it’s not entirely clear what the term ‘egalitarian society’ should even mean. Usually, it’s defined negatively: as the absence of hierarchies (the belief that certain people or types of people are superior to others), or as the absence of relations of domination or exploitation. This is already quite complex, and the moment we try to define egalitarianism in positive terms everything becomes much more so. On the one hand, ‘egalitarianism’ (as opposed to ‘equality’, let alone ‘uniformity’ or ‘homogeneity’) seems to refer to the presence of some kind of ideal. It’s not just that an outside observer would tend to see all members of, say, a Semang hunting party as pretty much interchangeable, like the cannon-fodder minions of some alien overlord in a science fiction movie (this would, in fact, be rather offensive); but rather, that Semang themselves feel they ought to be the same – not in every way, since that would be ridiculous, but in the ways that really matter. It also implies that this ideal is, largely, realized. So, as a first approximation, we can speak of an egalitarian society if (1) most people in a given society feel they really ought to be the same in some specific way, or ways, that are agreed to be particularly important; and (2) that ideal can be said to be largely achieved in practice.

Another way to put this might be as follows. If all societies are organized around certain key values (wealth, piety, beauty, freedom, knowledge, warrior prowess), then ‘egalitarian societies’ are those where everyone (or almost everyone) agrees that the paramount values should be, and generally speaking are, distributed equally. If wealth is what’s considered the most important thing in life, then everyone is more or less equally wealthy. If learning is most valued, then everyone has equal access to knowledge. If what’s most important is one’s relationship with the gods, then a society is egalitarian if there are no priests and everyone has equal access to places of worship. You may have noticed an obvious problem here. Different societies sometimes have radically different systems of value, and what might be most important in one – or at least, what everyone insists is most important in one – might have very little to do with what’s important in another. Imagine a society in which everyone is equal before the gods, but 50 per cent of the population are sharecroppers with no property and therefore no legal or political rights. Does it really make sense to call this an ‘egalitarian society’ – even if everyone, including the sharecroppers, insists that it’s really only one’s relation to the gods that is ultimately important? There’s only one way out of this dilemma: to create some sort of universal, objective standards by which to measure equality. Since the time of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Adam Smith, this has almost invariably meant focusing on property arrangements. As we’ve seen, it was only at this point, in the mid to late eighteenth century, that European philosophers first came up with the idea of ranking human societies according to their means of subsistence, and therefore that hunter-gatherers should be treated as a distinct variety of human being. As we’ve also seen, this idea is very much still with us. But so is Rousseau’s argument that it was only the invention of agriculture that introduced genuine inequality, since it allowed for the emergence of landed property. This is one of the main reasons people today continue to write as if foragers can be assumed to live in egalitarian bands to begin with – because it’s also assumed that without the productive assets (land, livestock) and stockpiled surpluses (grain, wool, dairy products, etc.) made possible by farming, there was no real material basis for anyone to lord it over anyone else. Conventional wisdom also tells us that the moment a material surplus does become possible, there will also be full-time craft specialists, warriors and priests laying claim to it, and living off some portions of that surplus (or, in the case of warriors, spending the bulk of their time trying to figure out new ways to steal it from each other); and before long, merchants, lawyers and politicians will inevitably follow. These new elites will, as Rousseau emphasized, band together to protect their assets, so the advent of private property will be followed, inexorably, by the rise of ‘the state’. We will scrutinize this conventional wisdom in more detail later. For now, suffice to say that while there is a broad truth here, it is so broad as to have very little explanatory power. For sure, only cereal-farming and grain storage made possible bureaucratic regimes like those of Pharaonic Egypt, the Maurya Empire or Han China. But to say that cereal-farming was responsible for the rise of such states is a little like saying that the development of calculus in medieval Persia is responsible for the invention of the atom bomb. It is true that without calculus atomic weaponry would never have been possible. One might even make a case that the invention of calculus set off a chain of events that made it likely someone, somewhere, would eventually create nuclear weapons. But to assert that Al-Tusi’s work on polynomials in the 1100s caused Hiroshima and Nagasaki is clearly absurd. Similarly, with agriculture. Roughly 6,000 years stand between the appearance of the first farmers in the Middle East and the rise of what we are used to calling the first states; and in many parts of the world, farming never led to the emergence of anything remotely like those states.7 At this juncture, we need to focus on the very notion of a surplus, and the much broader – almost existential – questions it raises. As philosophers realized long ago, this is a concept that poses fundamental questions about what it means to be human. One of the things that sets us apart from non-human animals is that animals produce only and exactly what they need; humans invariably produce more. We are creatures of excess, and this is what makes us simultaneously the most creative, and most destructive, of all species. Ruling classes are simply those who have organized society in such a way that they can extract the lion’s share of that surplus for themselves, whether through tribute, slavery, feudal dues or manipulating ostensibly free-market arrangements. In the nineteenth century, Marx and many of his fellow radicals did imagine that it was possible to administer such a surplus collectively, in an equitable fashion (this is what he envisioned as being the norm under ‘primitive communism’, and what he thought could once again be possible in the revolutionary future), but contemporary thinkers tend to be more sceptical. In fact, the dominant view among anthropologists nowadays is that the only way to maintain a truly egalitarian society is to eliminate the possibility of accumulating any sort of surplus at all.

Graeber, David. The Dawn of Everything (pp.125-128). Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Edizione del Kindle.

Unblocking human possibilities

Kairos

take back our social creativity

Marianella Sclavi

Benjamin's critique of violence: negotiation and "pure means" vs Gewalt

western rationality as described by Max Weber is, in fact, a form of stupidity - or, better said, of violent reduction of complexity

how state and capital appropriate social creativity and social bureaucracy:

bureaucracy (DoE ch. 10)

communism (Utopia)

all possibilities are always present, but following the circumstancies and, above all, the #self-conscious choices of a group or a civilization, some are prevalent (elaborate / find out how it works)

revolution (Fragments)

how does a civilzation decide? Imagination, conversation ... dispel the myth of the Great Man

Far from being the dead end of human civilization, our times are a Kairos, one of these moments of great historical transformation where what we do makes the most difference5. If a Dawn of Everything has ever existed, it is now, not in a remote foundational past that cannot anymore be changed or redeemed.

DoE, conclusions

Hope, in BBC podcast

it is quite clear, now, why Rousseau couldn't understand Kandiarok's idea of freedom: property (C.B. MacPherson,The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: From Hobbes to Locke, Oxford UP 1962)

and why the European answer to the Indigenous' critique's challenge was to reduce everything to the means of production

violence and imagination

violence as cutting out complexity - the same logic as avoidance

Utopia: violence and stupidity

imagination and building a new social order

Utopia

imagination as a repository of possibilities

Fragments

Use of anthropology: anthropological

appraisal of our culture

European notion of equality

with its reductionist view of what is "material" (reducing material to exchange value), marxism is in the same frame (Max Weber:

All economies are ultimately human economies

Turning modes of production ...

Possibilities: the transition from the world of Rabelais to that of Queen Victoria, Elias' manners, puritan and controriformist war on popular culture are part of the same historical process that led to absolute private property and commercialization of everyday life

what's specific of European civilization:

freedom

#possessive_individualism

sacred items are, in many cases, the only important and exclusive forms of property that exist in societies where personal autonomy is taken to be a paramount value, or what we may simply call ‘free societies’. It’s not just relations of command that are strictly confined to sacred contexts, or even occasions when humans impersonate spirits; so too is absolute – or what we would today refer to as ‘private’ – property. In such societies, there turns out to be a profound formal similarity between the notion of private property and the notion of the sacred. Both are, essentially, structures of exclusion. Much of this is implicit – if never clearly stated or developed – in Émile Durkheim’s classic definition of ‘the sacred’ as that which is ‘set apart’: removed from the world, and placed on a pedestal, at some times literally and at other times figuratively, because of its imperceptible connection with a higher force or being. Durkheim argued that the clearest expression of the sacred was the Polynesian term tabu, meaning ‘not to be touched’. But when we speak of absolute, private property, are we not talking about something very similar – almost identical in fact, in its underlying logic and social effects? As British legal theorists like to put it, individual property rights are held, notionally at least, ‘against the whole world’. If you own a car, you have the right to prevent anyone in the entire world from entering or using it. (If you think about it, this is the only right you have in your car that’s really absolute. Almost anything else you can do with a car is strictly regulated: where and how you can drive it, park it, and so forth. But you can keep absolutely anyone else in the world from getting inside it.) In this case the object is set apart, fenced about by invisible or visible barriers – not because it is tied to some supernatural being, but because it’s sacred to a specific, living human individual. In other respects, the logic is much the same. To recognize the close parallels between private property and notions of the sacred is also to recognize what is so historically odd about European social thought. Which is that – quite unlike free societies – we take this absolute, sacred quality in private property as a paradigm for all human rights and freedoms. This is what the political scientist C. B. Macpherson meant by ‘possessive individualism’. Just as every man’s home is his castle, so your right not to be killed, tortured or arbitrarily imprisoned rests on the idea that you own your own body, just as you own your chattels and possessions, and legally have the right to exclude others from your land, or house, or car, and so on.53 As we’ve seen, those who did not share this particular European conception of the sacred could indeed be killed, tortured or arbitrarily imprisoned – and, from Amazonia to Oceania, they often were.54 For most Native American societies, this kind of attitude was profoundly alien. If it applied anywhere at all, then it was only with regard to sacred objects,

Graeber, David. The Dawn of Everything (pp.158-160). Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Edizione del Kindle.

individual freedom as private #property DoE 66-7

DoE pp. 66-67 The European conception of individual freedom was, by contrast, tied ineluctably to notions of private property. Legally, this association traces back above all to the power of the male household head in ancient Rome, who could do whatever he liked with his chattels and possessions, including his children and slaves. In this view, freedom was always defined – at least potentially – as something exercised to the cost of others. What’s more, there was a strong emphasis in ancient Roman (and modern European) law on the self-sufficiency of households; hence, true freedom meant autonomy in the radical sense, not just autonomy of the will, but being in no way dependent on other human beings (except those under one’s direct control). Rousseau, who always insisted he wished to live without being dependent on others’ help (even as he had all his needs attended to by mistresses and servants), played out this very same logic in the conduct of his own life.

equality

Different societies sometimes have radically different systems of value, and what might be most important in one – or at least, what everyone insists is most important in one – might have very little to do with what’s important in another. Imagine a society in which everyone is equal before the gods, but 50 per cent of the population are sharecroppers with no property and therefore no legal or political rights. Does it really make sense to call this an ‘egalitarian society’ – even if everyone, including the sharecroppers, insists that it’s really only one’s relation to the gods that is ultimately important? There’s only one way out of this dilemma: to create some sort of universal, objective standards by which to measure equality. Since the time of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Adam Smith, this has almost invariably meant focusing on #property arrangements.

property (Roman Law notion of)

going back to Max Weber’s question: what is so peculiar about the West that here, and only here, was developed this peculiar form of rationality that now shapes what we understand as science, reason, and universal values?

DoE - what MW "protestant ethics" is really about

our current predicament is not universal (its universality has been built by violence), it is historically placed

asking big questions, the great tradition

escaping the colonialist traps of the great tradition, and evolution too

#Mauss: almost all social possibilities—democracy and monarchy, individualism and communism, gifts and money—are simultaneously present in any social context, and always have been, and that all that really varies from age to age is how they come together, and which tend to be seized on and promoted over the others as the truly defining features of society or human nature.

instead of stages of history being based on opposed principles, everything exists at once: gifts, commodities, patronage, exploitation. It is a question of emphasis and articulation.

use of anthropology: show possibilities, dispel the myths

show that there are different ways

(Possibilities)

The war on imagination

Unfreeze the imagination

We stick to the current predicament because we cannot imagine alternatives. Yet these alternatives do exist. They existed in the past, they still exist in other present-day civilizations, and they exist in the very inside of our western world, in forms that go unnoticed, because our common sense makes them look trivial and unimportant, or simply puts them in a blind spot. More importantly, we are able – collectively – to imagine and create alternatives:

Is not the capacity to experiment with different forms of social organization itself a quintessential part of what makes us human. That is, beings with the capacity for self-creation, even freedom?

We are projects of mutual self-creation, and it can be argued that the very essence of human beings is imagination (see Utopia of rules), and the ability to imagine and reinvent ourselves and to collectively reshape or social relationships.

If, as many are suggesting, our species’ future now hinges on our capacity to create something different (say, a system in which wealth cannot be freely transformed into power, or where some people are not told their needs are unimportant, or that their lives have no intrinsic worth), then what ultimately matters is whether we can rediscover the freedoms that make us human in the first place. As long ago as 1936, the prehistorian V. Gordon Childe wrote a book called Man Makes Himself. Apart from the sexist language, this is the spirit we wish to invoke. We are projects of collective self-creation. What if we approached human history that way? What if we treat people, from the beginning, as imaginative, intelligent, playful creatures who deserve to be understood as such? What if, instead of telling a story about how our species fell from some idyllic state of equality, we ask how we came to be trapped in such tight conceptual shackles that we can no longer even imagine the possibility of reinventing ourselves? [1]

If it is so then the essential endeavour of our times is to abandon the illusions that produce such a blindness, and reclaim our capacity to reinvent ourselves and collectively shape our future. Our capacity to imagine alternatives and self-consciously translate what we’ve imagined in reality.

This endeavour was David Graeber’s, and he pursued it in two ways: challenging the myths and the common sense assumptions that prevent us from imagining alternatives, and showing the possibilities and the alternatives that already exist in our very reality

[1]

we are stuck because we believe we are, but this belief is the result of a specific ideological construction

Hopelessness isn’t natural. It needs to be produced. If we really want to understand this situation, we have to begin by understanding that the last thirty years have seen the construction of

a vast bureaucratic apparatus for the creation and maintenance of hopelessness, a kind of giant

machine that is designed, first and foremost, to destroy any sense of possible alternative futures

What's the point, if we can't have fun?

Circular argument: why people dance?

(Introduction to Mutual Aid)

Nowadays, most of us find it increasingly difficult even to picture what an alternative economic or social order would be like. Our distant ancestors seem, by contrast, to have moved regularly back and forth between them.

If something did go terribly wrong in human history – and given the current state of the world, it’s hard to deny something did – then perhaps it began to go wrong precisely when people started losing that freedom to imagine and enact other forms of social existence, to such a degree that some now feel this particular type of freedom hardly even existed, or was barely exercised, for the greater part of human history.

It means we could have been living under radically different conceptions of what human society is actually about. It means that mass enslavement, genocide, prison camps, even patriarchy or regimes of wage labour never had to happen. But on the other hand it also suggests that, even now, the possibilities for human intervention are far greater than we’re inclined to think

#DoE, conclusion, p. 502

we are, and we have always been, creative beings able to reinvent ourselves

(DoE)

ThereIsNoAlternative

If we still participate in this march, it is because we cannot imagine alternatives.

We feel that even if the one we live in is far from being the best of the worlds, it is nevertheless the best of those that are possible. While we live mostly unhappy lives in polluted cities, while we work in underpaid jobs, or in jobs whose contribution to the wellbeing of humanity we doubt, or both, while we head towards the climate catastrophe, the stress in “the best of possible worlds” goes on "possible". Pursuing an infinite growth of production on our finite planet, as crazy and suicidal it can be, is the only line of action that we can imagine, as the despairing comedy of COP26 showed recently, because we believe that the only way to stop this inevitable march would be an impossible one: It would be to renounce civilization, and we cannot renounce civilization and technology, as we are very aware that our very survival depends on it.

We can't stop making capitalism, we believe. All we can do is putting patchs on the worst consequences of it: natural disasters, raising inequalities and overwhelming misery, forced migrations and wars. And this is what we are doing: putting larger and larger patchs, half hoping that this will avert the final catastrophe.

There’s only one alternative that we are able to imagine to this appalling perspective: a strict and comprehensive technical planning not only of production, but of all aspects of our lives, and a strict social control of individual compliance to the dictamens of this planning. : a bureaucratic nightmare that would at least allow humanity “to go on living, and partly living”

In many countries, given the management of the pandemic, it seems that we will have both capitalism and the bureaucratic nightmare.

market or bureaucracy (Utopia, c.1)

(oddly remembers Turgot)

the end of the idea of progress

David Graeber, Unblocking human possibilities

“The demand to abandon the illusions about people's condition is the demand to abandon a condition that needs illusions”. (Karl Marx, A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right)

“One of David's books is titled Possibilities. It is an apt description of all his work. It is an even better description of his life. Offering unimagined possibilities of freedom was his gift to us.” Marshall Sahlins

One century ago, we believed in a future of development and progress towards a better world, a world of scientific and technological achievements and of shared prosperity for the whole humanity, and we (the Western countries, that is) liked to think that European civilization, even if through violence and genocide, had brought in this progress.

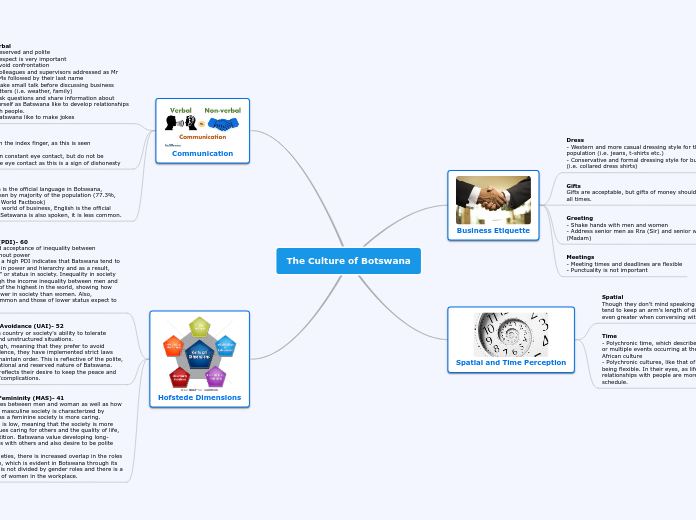

European civilization did so, following Max Weber, thanks to the development of rational forms of reasoning and universal values that only appeared on European soil: “what concatenation of circumstances”, he asked “have led to the fact that on the soil of the Occident, and only here, cultural phenomena have appeared which — at least as we like to think - lay in a direction of development of universal significance and validity?”. Only in the West, argues Max Weber, "science" exists in the stage of development that we recognise as valid today, since in other civilizations like ancient Babylonian astronomy, Indian geometry or Indian natural sciences and medicine, it either lacked the mathematical foundation and the rational proof, that are born from the Hellenic brain, or the rational experimentation which is essentially a product of the Renaissance. At the same time, he says, outside the West we cannot find rational concepts of politics, or a rational doctrine of law, or a rational and bureaucratic organisation of the State and of scientific research. Finally, it’s only in the West that we can find that kind of rational organization of work and production, based on measurability and on profit-oriented action that we call Capitalism[1].

Despite the disasters of the first and second world war, and the liberation movements that, at the middle of the XX century, shred off colonial domination, under many aspects this perspective has not changed much until today. We still believe in the universal significance and validity of Western civilization. We still believe in the historical task of western countries to bring civilization, democracy and universal human values to the whole of humanity - in case of necessity, through war. We also still believe that our present-day civilization is the ultimate product of a march started when we first developed our first technology, farming, which inevitably led to the development of cities and of hierarchical government.

Yet something essential has changed: we feel that something has gone terribly wrong with civilization. We do not anymore think of this march as progress towards a better world. On the very contrary, we think of it as an inevitable march towards catastrophe, since we are all aware that an infinite growth on a finite planet cannot but lead us to collapse, and perhaps to extinction.

If we still participate in this march, it is only because we can’t imagine alternatives.

[1] Max Weber, 1920 Vorbemerkung zu den »Gesammelten Aufsätzen zur Religionssoziologie«

we are stuck, cop26, mouses in a maze

our imagination has been so effectively stuck that we cannot see alternatives to: either take part in the inevitable march of economical growth, or altogether renounce a civilization we depend on for survival

it's not they are bad guys (they are) it's that from their role and inside their frame it's the most rational (and necessary) behavior

"please, allow us not to behave like that!"

capitalism as a SYSTEM, indipendent from individual

will

The idea of progress and of universal occidental values

Testo seminario Morelos