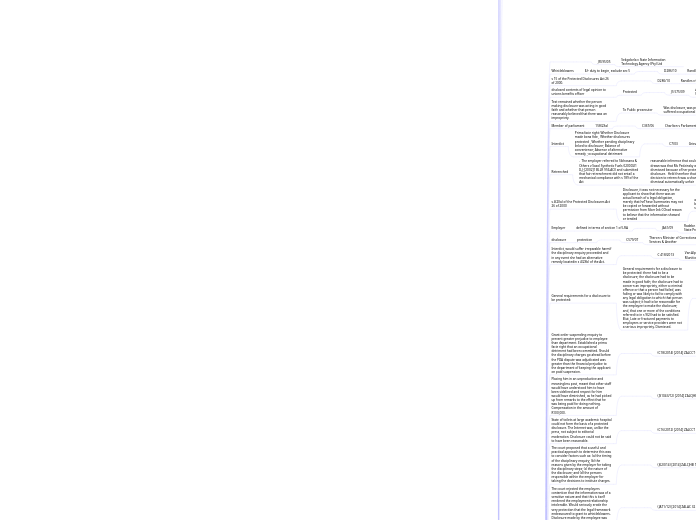

Labour Law cases decided in the South African Courts (Highlights and updated 1997 to December 2022 [Copyright: Marius Scheepers /10.1.1])

Varied topics: Administrative action, Administrative law, Collective agreement, Common law, Definition, Information, Interest dispute, Mutual interest vs rights issue, Nature of dispute, Parity principle, Protected disclosure act, Public Holidays Act 1994, Trade Union, Transfer of Employment, Unreasonable Delay Rule.

unreasonable delay rule

The aggrieved party at least had to place the offending party on terms, seek the intervention of the registrar of the labour court, or file an application to compel, prior to filing an application to dismiss.

does not apply where the Prescription Act applies, as was the case in this matter. The rule only applies to applications for review.

CA9/05

Solidarity & Others v Eskom Holdings Ltd

Transfer of employment

service provider

J 998 / 2022

AFMS GROUP (PTY) LTD vs SOUTH AFRICAN AIRWAYS (SOC) LTD

[57]...The new service provider would in fact step into the shoes of AFMS, seamlessly taking over the providing of the same services, using the systems of SAA to manage the same. Even though it is true that AFMS did not use the assets or infrastructure of SAA to provide the services, and rather provides the services on such assets or infrastructure, this factor in itself, considering all else, is insufficient to dispel the application of section 197 in this case

[36] A contract of employment is transferrable under the provisions of section 197 of the LRA, including all the terms agreed to between the parties, not only those that are more favourable than the provisions of the BCEA.

J 737/22

Slo Jo Innovation (Pty) Ltd v Beedle and Another (J 737/22) [2022] ZALCJHB 212 (10 August 2022)

[37] A restraint of trade agreement concluded between an employer and employee and included in a contract of employment, is transferable under section 197 of the LRA.

services extend beyond the maintenance of a physical installation

it moved from the hands of Red Mining not by a typical transfer but by Red Mining losing a contract

JS 633/18

Yeko v Red Mining South Deep (PTY) LTD (JS 633/18) [2022] ZALCJHB 74 (22 March 2022)

[15] This is not a case where section 197 of the LRA could have been employed. Red Mining lost a contract. It did not transfer its rail contract to Flint as a going concern. Of course, Flint was not obliged to take Yeko into employment once it was awarded the rail contract. There seems to be a lacuna in the LRA. In my view, technically Flint took over the business or service of Red Mining. Unfortunately, section 197(1) defines transfer to mean the transfer of a business by one employer (old employer) to another employer (the new employer). I have no doubt in my mind that the rail contract is a business or service. However, it moved from the hands of Red Mining not by a typical transfer but by Red Mining losing a contract that employed Yeko and others. Actually, where short term services vacillate from one business to another by way of tenders being won and lost, such, in my considered view, is not materially different from one business selling its business or part thereof to another business. If section 197 were to be expanded to situations, where a client awards a business or service to another company, much to the chagrin of another company, social justice will, in my view, be served. One of the stated purposes of the LRA, in section 1, is, amongst others to advance economic development and social justice. The purpose of section 197 is to protect individual contracts of employment and ultimately job security. A lacuna I spot creates an opportunity for companies like Gold Fields joint venture to weaken the job security of employees. At the end of the day, Gold Fields is the consumer of the services on the rail maintenance. It is the main benefactor. The fact that it can use companies through a tendering system to achieve its labour needs, without it being affected, as an old or new employer is worrying. It is no different to the labour brokerage situation in substance. They only differ in form. In fact, there was nothing to have prevented Gold Fields to directly hire Yeko and others to work on the rail maintenance or upgrade, even if it is for a limited duration. Section 198B (3) of the LRA makes provision for a limited duration employment. The fact that Gold Fields opted for outsourcing, places it on the same footing as temporary employment services situation. This Court is acutely aware of the raging debate that the so-called second-generation outsourcing being brought under the wing of section 197 somewhat stifles outsourcing as a legitimate business method. However, it may be ideal for the legislature to find means and ways to curb the apparent defeat of the LRA.

retrenched due to transfer.

JS 229/2020

Chauke v Imperial Managed Solutions SA (JS 229/2020) [2022] ZALCJHB 43 (11 March 2022)

[6] For reasons that are not apparent, the applicants representative elected to file a claim to the effect that the applicant had been unfairly retrenched, and limited the scope of the enquiry to the application of section 189. This requires the court to determine the substantive and procedural fairness of the applicants dismissal on account of Imperials operational requirements. Section 197 does not preclude either the transferee or transferor employer from dismissing an employee, pre- or post-transfer, by reason of operational requirements. Clause 4.1.3 of the section 197 agreement referred to above means no more than that for the purposes of section 197, the applicants employment would be transferred to Imperial on the same terms and conditions. It remains open to Imperial, as it did, to dismiss for operational requirements within the protections established by section 189. The LRA provides further, specific protection to employees whose employment is transferred in terms of section 197 in the form of section 187 (g), which provides that if the reason for dismissal is a transfer, or a reason related to a transfer, contemplated by section 197, the dismissal is automatically unfair. That formulation is broad in scope and permit scrutiny of any causal connection between the transfer and the dismissal that might exist. Obviously, a claim of automatically unfair dismissal in these circumstances must be pleaded, as must the case for causation that the applicant asserts. The categorisation of the present claim as one concerning a dismissal on account of operational requirements necessarily limits the scope of the courts enquiry, as I have indicated, to a determination of the substantive and procedural fairness of the applicants dismissal.

[10] In the circumstances, I am satisfied that Imperial engaged in a meaningful joint consensus-seeking process, in good faith, to honestly explore the prospects of an alternative to the applicants retrenchment, and that the requirements of procedural fairness have been satisfied.

Consultation

J 464/20

Comunication Workers Union v Mobile Telephone Networks South Africa (MTN SA) (J 464/20) [2020] ZALCJHB 170 (1 June 2020)

[30] The Applicants reliance on section 197(6) is misplaced. The Applicant does not have a right to consult or to negotiate or to request information in a section 197 transfer process where there is no agreement as contemplated in section 197(6), of which there is none in casu. In fact, it was conceded by Mr Ndlovu that section 197(6) finds no application in this matter.

Liquidation

J203/16

Baloi and Another v Maddox Adams Intrenational South Africa (Pty) Ltd (J203/16) [2018] ZALCJHB 264 (15 August 2018)

Hydro Colour Inks (Pty) Ltd v CEPPWAWU [2011] 7 BLLR 637 (LAC) at para 17.

I have already mentioned that the fact that Keep Inks is insolvent is common cause. Section 197A in so far as it states that the new employer is automatically substituted in the place of the old employer in all contracts of employment in existence immediately before the old employer's winding-up or sequestration finds application. It must be emphasised that the automatic substitution only relates to all "contracts of employment" in existence immediately before the old employer's winding-up or sequestration. This means that the new employer takes no responsibility for the actions of the old employer. By way of an example, any wrongful dismissal by the old employer remains a matter for the old employer.

Restaurant

J1598/16

Sodexo Southern Africa (Pty) Ltd v Servest (Pty) Ltd and Others (J1598/16) [2018] ZALCJHB 177 (11 May 2018)

See Aviation Union of SA and Another v SA Airways (Pty) Ltd and Others (2011) 32 ILJ 2861 (CC) (SAA).

[16] It is by now well established that whether there has been a transfer of a business as a going concern for purposes of section 197 is a matter of fact, to be determined objectively. This necessarily involves an enquiry into (1) the existence of a transfer from one employer to another, (2) whether there was a transfer of a business (is there an economic entity capable of being transferred?) and (3) whether the business is transferred as a going concern (does the economic entity that is transferred retain its identity after transfer?).

insourcing

JA122/2017

Imvula Quality Protection (Pty) Ltd and Others v University of South Africa (JA122/2017) [2018] ZALAC 33; [2018] 12 BLLR 1151 (LAC) (25 September 2018)

This arrangement cannot be said to fall within the meaning of a transfer of a business as a going concern, as contemplated by s 197 of the LRA.

Transfer as a going concern in terms of the notarial bonds

JA47/2017

Spar Group Limited v Sea Spirit Trading 162 CC t/a Paledi and Others (JA47/2017) [2018] ZALAC 15; (2018) 39 ILJ 1990 (LAC); [2018] 10 BLLR 1000 (LAC) (7 June 2018)

A creditor perfecting a notarial bond over movable property of its debtor normally does not intend to acquire responsibility for conducting the business of the debtor for the purpose of making profits on an ongoing basis...Requiring a creditor perfecting a notarial bond to assume responsibility for the employment contracts of the debtor will render this form of security unduly burdensome and less effective. Although the appellant assumed responsibility for conducting the business of the corporations, it did so temporarily with the limited purpose of recovering its debt.

20] The present situation bears resemblance, in a limited respect, to a change in shareholders through the sale of shares, where the new shareholder gains control of a business, but the business (i.e. the employer) remains intact and does not transfer to the new shareholder. In such cases control or responsibility for the business may be shifted, but the legal identity of the employer remains the same, as do the contractual relationships between the employer and employees. Section 197 of the LRA does not apply in these circumstances.[8] 21] The Labour Court therefore erred in finding there was a transfer of business and that section 197 of the LRA was applicable in these circumstances.

Promotion

JR350/16

Letsogo v Department of Economy and Enterprise Development and Others (JR350/16) [2018] ZALCJHB 48 (9 January 2018)

Ga-Segonyana Local Municipality v Venter N.O. and Others (JR961/13) [2016] ZALCJHB 391; (11 October 2016).

City of Cape Town v SA Municipal Workers Union on behalf of Sylvester & others (2013) 34 ILJ 1156 (LC), in further reference to Aries v CCMA and others (2006) 27 ILJ 2324 (LC).

held that the overall test is one of fairness, and that in deciding whether or not the employer had acted unfairly in failing or refusing to promote the employee, relevant factors to consider include whether the failure or refusal to promote was caused by unacceptable, irrelevant or invidious considerations on the part of the employer; or whether the employers decision was motivated by bad faith, was arbitrary, capricious, unfair or discriminatory; whether there were insubstantial reasons for the employers decision not to promote; whether the employers decision not to promote was based upon a wrong principle or was taken in a biased manner; whether the employer failed to apply its mind to the promotion of the employee; or whether the employer failed to comply with applicable procedural requirements related to promotions. The list is not exhaustive. [21] Central to appointments or promotion of employees is the principle that that courts and commissioner alike should be reluctant, in the absence of good cause, to interfere with the managerial prerogative of employers in making such decisions

City of Cape Town v SA Municipal Workers Union obo Sylvester and Others (C1148/2010) [2012] ZALCCT 40; [2013] 3 BLLR 267 (LC); (2013) 34 ILJ 1156 (LC) (7 September 2012).

joinder of new employer

the court expressly rejected the notion that the employer has the prerogative to decide who to appoint and that it should not be questioned when it exercises that discretion. The court stated that the proper yardstick was fairness to both parties.

CA11/2016

High Rustenberg Estate (Pty) Ltd v NEHAWU obo Cornelius and Others (CA11/2016) [2017] ZALAC 20; (2017) 38 ILJ 1758 (LAC) (23 March 2017)

[21] ...The purpose of the initial order of this Court, was that because the new employer had not been heard, a stated case should be decided by the court a quo in circumstances where the appellant, being the new employer, would have an opportunity to present its case. If an attachment of property takes place, it does appear that the new employer has to be joined to such proceedings. However, the question of joinder cannot on its own trump the wording of s 197 (5) of the LRA, read in terms of its purpose, namely that if an award is binding on the old employer it is deemed to be binding on the new employer. The fact that the Labour Court substitutes the formulation of the award for the one which is set aside cannot detract from this conclusion, for, if it did, it would ultimately damage the very purpose of s 197, namely to protect employee rights in the context of a sale of a business as a going concern.

Service

J435/17

Imvula Quality Protection and Others v University of South Africa (J435/17) [2017] ZALCJHB 310; [2017] 11 BLLR 1139 (LC); (2017) 38 ILJ 2763 (LC) (31 August 2017)

iMvula and Red Alert retain all of the other components that go to make up their respective businesses. They will be free to offer their services to other clients, and to deploy those employees not engaged by UNISA on other sites, should posts be available. The true position therefore is that the contracts for the provision of services concluded between UNISA and iMvula and Red Alert respectively have come to an end, and that no part of the infrastructure for the conducting of the business of providing a security service is to be transferred to UNISA. In those circumstances, UNISAs decision to insource in terms of the shared services model and the offers of employment consequently made to some of iMvula and Red Alerts staff does not trigger s 197.

Application of s 197 to insourcing of security services. Insourcing limited to the making of offers of employment to certain of the outgoing contractors employees. In terms of a shared services model, clients role after termination limited to employment, client not taking transfer of any business infrastructure. Third party to be appointed to provide management and infrastructure for security services. Held that there is no business that is the subject of any transfer and that s 197 thus not applicable.

National Health and Allied Workers Union v University of Cape Town & others (2003) 24 ILJ 95 (CC)

[52] What lies at the heart of disputes on transfers of businesses is a clash between, on the one hand, the employers interest in the profitability efficiency or survival of the business, or if need be its effect is of disposal of it, and the workers interest in job security and the right to freely choose an employer on the other hand[53] Section 197 . relieves the employers and the workers of some of the consequences that the common law visited on them. Its purpose is to protect the employment of the workers and to facilitate the sale of businesses as going concerns by enabling the new employer to take over the workers as well as other assets in certain circumstances. The section aims at minimising the tension and the result labour disputes that often arise from the sales of businesses and impact negatively on economic development and labour peace. In this sense, s 197 has a dual purpose, it facilitates the commercial transactions while at the same time protecting workers against job losses

[18] In essence, the court is required to determine whether UNISAs termination of its contracts with iMvula and Red Alert and its decision to employ the majority of their employees engaged on the contract, constitutes the transfer of a business as a going concern for the purposes of s 197.

employment perspective

J890/17

Tasima (Pty) Ltd v Road Traffic Management Corporation and Others (J890/17) [2017] ZALCJHB 198; (2017) 38 ILJ 2385 (LC) (25 May 2017)

COSAWU v Zikhethele Trade (Pty) Ltd

[T]he decisive criterion for determining whether there has been a transfer of an undertaking (read business) is whether, after the alleged transfer, the undertaking has retained its identity, so that employment in the undertaking is continued or resumed in the different hands of the transferee. In order to determine whether there has been a retention of identity it is necessary to examine all the facts relating both to the identity of the undertaking and the relevant transaction and assess their cumulative effect, looking at the substance, not at the form, of the arrangements. The mode or method of transfer is immaterial. The emphasis is on a comparison between the actual activities of and actual employment situation in an undertaking before and after the alleged transfer. Kelman v Care Contract Services [1995] ICR 260. What seems to be critical is the transfer of responsibility for the operation of the undertaking. Mummery Js conclusion in Kelman offers a salutary guideline. He said:

Kelman v Care Contract Services [1995] ICR 260.

The theme running through all the recent cases is the necessity of viewing the situation from an employment perspective, not from a perspective conditioned by principles of property, company or insolvency law. The crucial question is whether, taking a realistic view of the activities in which the employees are employed, there exists an economic entity which, despite changes, remains identifiable, though not necessarily identical, after the alleged transfer.

[31] But in South African law, no court including the highest court has made this distinction. In City Power the Constitutional Court specifically dealt with the question whether section 187 applies to a municipal entity. It found that it does. It also applied s 197 to organs of state or public authorities in Rural Maintenance and in NEHAWU v UCT. Interpreting the legislation with its purpose in mind, I can see no reason to create such a distinction now.

retrenchment

JS230/15

Du Plessis v Amic Trading (Pty) Ltd t/a Toy's R Us (JS230/15) [2017] ZALCJHB 196 (23 May 2017)

Van der Velde v Business & Design Software (Pty) Ltd & Another (2006) 27 ILJ 1738 (LC) at 1748-9[2008] ZALC 80; ; [2006] 10 BLLR 1004 (LC) at 1014-5.

In summary, and in an attempt to crystallise these views and to formulate a test that properly balances employer and worker interests, the legal position when an applicant claims that a dismissal is automatically unfair because the reason for dismissal was a transfer in terms of section 197 or a reason related to it, is this: the applicant must prove the existence of a dismissal and establish that the underlying transaction is one that falls within the ambit of section 197; the applicant must adduce some credible evidence that shows that the dismissal is causally connected to the transfer. This is an objective enquiry, to be conducted by reference to all of the relevant facts and circumstances. The proximity of the dismissal to the date of the transfer is a relevant but not determinative factor in this preliminary enquiry; if the applicant succeeds in discharging these evidentiary burdens, the employer must establish the true reason for dismissal, being a reason that is not automatically unfair; when the employer relies on a fair reason related to its operational requirements (or indeed any other potentially fair reason) as the true reason for dismissal, the Court must apply the two-stage test of factual and legal causation to determine whether the true reason for dismissal was the transfer itself, or a reason related to the employers operational requirements; the test for factual causation is a but for test would the dismissal have taken place but for the transfer? if the test for factual causation is satisfied, the test for legal causation must be applied. Here, the Court must determine whether the transfer is the main, dominant, proximate or most likely cause of the dismissal. This is an objective enquiry. The employers motive for the dismissal and how long before or after the transfer the employee was dismissed, are relevant but not determinative factors. if the reason for dismissal was not the transfer itself (because, for example, it was a dismissal effected in anticipation of a transfer and in response to the requirements of a potential purchaser of the business) the true reason may nonetheless be a reason related to the transfer; to answer this question (whether the reason was related to the transfer) the Court must determine whether the dismissal was used by the employer as a means to avoid its obligations under section 197. (This is an objective test, which requires the Court to evaluate any evidence adduced by the employer that the true reason for dismissal is one related to its operational requirements, and where the employers motive for the dismissal is only one of the factors that must be considered). if in this sense the employer used the dismissal to avoid it section 197 obligations, then the dismissal was related to the transfer; and if not, the reason for dismissal relates to the employers operational requirements, and the Court must apply section 188 read with section 189 of the LRA to determine the fairness of the dismissal.

declaringorder

J2718/2016

Fraser Alexander (Pty) Limited v Instasol Tailings (Pty) Limited and Others (J2718/2016) [2016] ZALCJHB 523 (5 December 2016)

(1) There must be the transfer, the whole or part of a business, as a going concern. The first element (the existence of a transfer) in circumstances such as the present is not controversial - the termination by a client of an agreement with one service provider and the conclusion of an agreement with another for the provision of similar services, is capable of constituting a transfer. In particular, the courts have held that the absence of a contractual nexus between the outgoing and incoming contractors does not preclude the application ofs 197... (2) In relation to the existence of a the whole or part of a busines... n economic entity , or an organised grouping of employees and assets facilitated the exercise of an economic activity. Although the ECJ has made clear that an entity cannot be reduced to the activity entrusted to it, the relevant UK regulations include a service provision change within the scope of what is contemplated as a business. In any event, as this court observed in Harsco, the definition of business in s 197(1) is broad, and it is difficult to conceive of an economic entity that would not comprise a business for the purposes of s197. Whether a business is transferred as a going concern is the subject of a multi-factoral enquiry established by Nehawu v University of Cape Town, and referred to below....(the ECJ in Spijkers v Gebroeders Benedick Abattoir v Alfred Benedik en Zonen BV [1986] 2 CMLR 286 (ECJ) where the ECJ held that the decisive criterion is whether the business concerned retains its identity after the transfer. That would be indicated, amongst other things, by the fact that the operation is actually continued or resumed by the new employer, with the same or similar activities.)...(Aviation Union of SA & another v SAA Airways (Pty) Ltd & others (2009) 30 ILJ 2849 (LAC) and National Education Health & Allied workers Union v University of Cape Town & others (2003) 24 ILJ 95 (CC))...

[37] In summary: Intasol will perform services at the same site and in doing so, it will carry on the same activity for the same client, Harmony. Intasol will utilise infrastructure provided by Harmony and previously utilised by the applicant. Intasol has engaged with certain of the applicants employees with a view to employing them on the same site, and it is open to employing at least 84 of the applicants employees on the same site to perform the same work but on different (less favourable) conditions of employment. For the above reasons, in my view, the termination by Harmony of its contracts with the applicant and the appointment of Intasol to provide the same services constitutes a change to the identity of the party who has had the conduct of activities to which an organised group of employees has been principally dedicated for a particular client. There is thus a transfer of a business as a going concern for the purposes ofs 197of the LRA.

Section 189 claim upheld

JS66/2009

National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa and Others v Niclotte (Edms) Beperk and Others (JS66/2009) [2016] ZALCJHB 170 (4 May 2016)

City Power (Pty) Ltd v Grinpal Energy Management Services (Pty) Ltd and others

In essence, the approach adopted inNEHAWUfollows that of the European Court of Justicein the application of the Business Transfers Directive (2001/23/EC) which is applicable in the European Union, and dictates that a transfer must relate to an autonomous economic entity (defined to mean an organized group of persons and assets facilitating the pursuit of an economic activity that promotes a specific objective). In turn this involves a determination whether that entity retains its identity after the transfer; that is, the transferor must carry on the same or similar activities with the personnel and/or the business assets without substantial interruption...The question is whether the activities conducted by a party, such as first respondent, constitute a defined set of activities which represents an identifiable business undertaking so that when a termination of an agreement between first respondent and appellant takes place, it can be said that this set of activities, which constitutes a discrete business undertaking, has now been taken over by another party

Unitrans

To the extent that the contractual right to provide warehousing services now vests in TMS, the same assets are used to provide those services and the activities conducted at Nampaks behest are substantially the same as those performed by the first applicant prior to 1 February, the business performed by the first applicant has transferred as a going concern to TMS.

[80]The Court inUnitransaccepted that a change in service providers triggered the application of section 197 in circumstances where the incoming contractor is permitted the right of use of infrastructural assets owned by the client necessary for the purpose of continuing the relevant service.

J389/16

Sodexo Southern Africa (Pty) Ltd v Olives and Plates Foods 2 (Pty) Ltd and Others (J389/16) [2016] ZALCJHB 136 (29 March 2016)

The catering services provided at the Multichoice restaurants and coffee shops is an economic entity and constitutes a service for purposes of section 197(1)(a).

Where Olives acquired the right of use of the infrastructural assets and where it will provide the same service from the same premises the business was transferred as a going concern and it falls within the ambit of section 197.

SeeAviation Union of SA and another v SA Airways (Pty) Ltd and others (2011) 32 ILJ 2861 (CC), Franmann Services (Pty) Ltd v Simba (Pty) Ltd and another(2013) 34 ILJ 897 (LC), Aviation Union of SA and another v SA Airways (Pty) Ltd and others (Aviation) (2011) 32 ILJ 2861 (CC) at paragraph 71, TMS Group Industrial Services (Pty) Ltd v Unitrans Supply Chain Solutions (Pty) Ltd and others (2015) 36 ILJ 197 (LAC) at paragraphs 25 and 26, City Power (Pty) Ltd v Grinpal Energy Management Services (Pty) Ltd and others (2014) 35 ILJ 2757 (LAC), TMS Group Industrial Services (Pty) Ltd v Unitrans Supply Chain Solutions (Pty) Ltd and others (2015) 36 ILJ 197 (LAC).

JA79/2014

MALUTI-A-PHOFUNG LOCAL MUNICIPALITY

Court of Appeal in P and O Trans-European Limited v Initial Transport Services Limited

to determine whether the conditions for the transfer of an economic entity are satisfied, it is also necessary to consider all the factual circumstances characterising the transaction in question, including in particular the type of undertaking or business involved, whether or not its tangible assets such as buildings and movable property are transferred, the value of its intangible assets at the time of the transfer, whetehr or not the core of its employees are taken over by the new employer, whether or not its customers are transferred, the degree of similarity between the activities carried on before and after the transfer, and the period, if any, for which those activities were suspended. These are, however, merely single factors in the overall assessment which must be made, and cannot therefore be considered in isolation (see in particular Spijkers paragraph 13 and Szen paragraph 14).[14] See also Wynn-Evans The Law of TUPE Transfers (Oxford University Press 2013) at 41-44.

In support of his submission on this point, MrVan der Merwemade reference to a number of cases, includingSACCAWU v Shoprite Checkers(Pty)Limited[1997] 10 BLLR 1360 (LC)[also reported at[1998] JOL 1686(LC)Ed];Hultzer v Standard Bank of South Africa[1999] 8 BLLR 809 (LC)[also reported at[1999] JOL 4896(LC)Ed] andUniversity of the Western Cape Academic Staff Union and others v University of the Western Cape(1999) 20 ILJ 1300 (LC). The principle established in these cases is one that inclines this Court to avoid granting what amounts to status quo relief in unfair dismissal disputes pending a final determination of the dispute by the appropriate dispute resolution body. None of these cases, it seems to me, establishes that financial hardship and loss of income can never be grounds for urgency. If an applicant is able to demonstrate detrimental consequences that may not be capable of being addressed in due course and if an applicant is able to demonstrate that he or she will suffer undue hardship if the court were to refuse to come to his or her assistance on an urgent basis, I fail to appreciate why this Court should not be entitled to exercise a discretion and grant urgent relief in appropriate circumstances. Each case must of course be assessed on its own merits.

Transfer of employment contracts where a business was transferred as a going concern and where employees were dismissed because of a transfer, the dismissal was automatically unfair.

performed the services previously provided by Interaction in the form of a call centre. Services were rendered to the same category of clients and the main business objective remained exactly as it had during the duration of the agreement. The same operational methods of rendering services were pursued by MTN. Furthermore, MTN took over a significant part of Interactions former employees together with a significant number of agents, all of whom were assigned to provide a necessary service.

Sufficient to fall within the scope of s 197 of the LRA.

Joinder

Court holding that transferee party had a clear and substantial interest in the matter and had to be joined.

An alleged employer who had not been part of conciliation proceedings with dismissed employees. s 197(9) transfer, the old and new employers were jointly and severally liable in respect of any claim concerning any term or condition of employment that arose prior to the transfer and s 197(2)(a) provided that the new employer was automatically substituted in the place of the old employer in respect of all contracts of employment in existence immediately before the date of transfer.

197A

Label of section 197A in contract not significant when all the indications were to the contrary.

197: Basis by which to determine whether there had been a transfer of business as a going concern by an old employer to a new employer:

Operation services constituted a discrete business; assets and infrastructure in order to continue to provide the same service; services could only be performed at the production facility; make use of the same equipment and IT systems

197: All of the assets, both tangible and intangible were transferred to the appellant. The business was identifiable and it was discrete. It involved equipment and expertise which was required to continue the project of providing electricity. When the court a quo referred to the appellant acting in a holding operation, it clearly meant that the appellant would run the business in the interim, until such time as a new contract was concluded with a third party.

Aviation Union of South Africa and Another v South African Airways (Pty) Ltd and Others 2012 (1) SA 321 (CC).

197: Going concern: same equipment and IT systems, constituted an economic entity, the contractual right to perform the services, the assets owned were used, would provide the same services from the same premises, without interruption, constituted a transfer as a going concern.

197: It did not appear there was a transfer of business as a going concern. were transferred from Retail to Supply Chain. There were no changes to their terms and conditions of employment. The respondents disputed that there was any need to consult as the affected employees consented to a transfer.

197: He refused to sign the restraint of trade agreement. Amounted to a fundamental change to the terms and conditions of his employment that were clearly less favourable. Dismissal was procedurally unfair and the applicant was to be paid an amount equal to 12 months.

(JS 574/2011) [2013] ZALCJHB 160

Suraci v Master Business Associates Holdings (Pty) Ltd

accompanying assets were transferred back to the municipality or to the MEC and that the first respondent was making use of the same employees that were in the employ of Remant prior to the termination of the contract between Remant and the municipality. Was any transfer of thebusiness to the MEC at all. In the evidence of the applicant there was no longer anybusiness running when Remant ceased its operations. The provision of a municipal busservice was not a business as contemplated in s 197 of the Act, but rather the exercise of astatutory obligation imposed on the second respondent and which had to be undertakenregardless of the question of profit. Had in fact ceased operations priorto such transfer.

A snapshot taken of the businesses onthe next day or any day thereafter, would reveal a similar picture.

Two questions had to be answered: Did the transaction create rights and obligations that required one entity to transfer something in favor of/or for the benefit of another or to another? If the answer was in the affirmative, then the question was whether the obligation imposed within the transaction contemplated a transferor who had the obligation to effect a transfer or allow a transfer to happen and a transferee who received the transfer. This was notthe equivalent situation to that of an outsourcing agreement.

PA 08/10

PE Pack 4100CC v Sanders and Others

City Power had stated its clear intention that it would take over all of the services rendered by the applicant in terms of the service agreements.

no assets, tangible or intangible, goodwill and the like that was to be transferred, and in the absence of any specific evidence relating to the use of any of Simbas assets or infrastructure, there was no transfer as a going concern.

S 197A

Transfer test

only contracts of employment transferred

not wrongful dismissal

JA48/07; 77/09

Hydro Colours Inks (Pty) Ltd v Chemical, Energy, Paper, Printing, Wood and Allied Workers Union

Right to be heard; Public sector employer must provide opportunity for representations prior to taking decision to transfer employee

failure to afford the employee an opportunity to make representations prior to the decision vitiated the transfer decision and the decision therefore was void, invalid and without legal effect.

took place despite its trading possibly having been interrupted for a limited period; factors that were relevant

National Education Health and Allied Workers Union v University of Cape Town & Others (2002) 23 ILJ 306 (LAC).[(2003) 24 ILJ 95 (CC).]

JA43/06

Ponties Panel Beaters Partnership v NUMSA & Others

took place despite its trading possibly having been interrupted for a limited period

SAMWU v Rand Airport Management Co Ltd [2005] 3 BLLR 241 (LAC)

Section 197; there was an economic entity capable of being transferred

there existed an economic entity which, despite changes, remained identifiable, though not necessarily identical, after the transfer

Sale of business

Services performed transferred to new contractors after a tender process

Some of assets used in performance of services transferred and majority of employees transferred

S197

"from"-"by"

consider location, nature of business

Transfer not complete until agreement reached; ongoing payment of travelling allowances and arrangements

Consent of employee not required to the transfer; Transfer automatic unless employee opts for redundancy or wave right for transfer

Van der Velde v Business and Design Software (Pty) Ltd and Another (2006) 27 ILJ 1225 (LC), in which it was found that s 197 of the LRA created a statutory exception to the common law, in that if a business is transferred as a going concern, one employer was as a matter of law substituted for another, irrespective of the consent of the employee.

whether in any particular situation a business has in fact been transferred as a going concern had to be determined objectively in light of the unique facts and circumstances of each case, with due regard to the substance and not the form of the transaction

no right to consultation when a business is transferred as a going concern arises under the provision of s 197.

Outsourcing; not all outsourcing transactions covered by s 197

business: Discrete economic entity in the sense of an organized grouping of persons and assets facilitating the exercise of an economic activity which pursues an economic objective

Transfer of business as going concern; Agreement

without agreement of employees

197(6)

Transfer was the main dominant, proximate, likely cause of dismissal

Employee dismissed subsequent to transfer has to produce sufficient evidence to raise a credible possibility that an automatically unfair dismissal has taken place

Transfer of a business as a going concern

Date on which the transaction is completed and the new employer takes unencumbered transfer of business

going concern

what happened to the goodwill of the business, the stock in trade, the premises, contracts with clients or customers, the workforce and the assets of the business; whether there has been an interruption of the operation of the business and, if so, its duration; and whether the same or similar activities are continued after the transfer.

[W]hat is transferred must be a business in operation so that the business remains the same but in different hands. This must be determined objectively in the light of the circumstances of each transaction.

JS546/05

CEPPWAWU & Others v Cordebo & Another

going concern; 197

such as the transfer or otherwise assets, both tangible or intangible, whether or not workers are taken over by the new employer, whether customers are transferred and whether or not the same business has been carried on by the new employer.

no business entity on its own

Employee dismissed as a direct result of transfer of a business as a going concern

197

Transfer of business as a going concern

Acquisition of all the shares of a company not triggering provisions of s 197

Automatically Unfair dismissal

whether he was dismissed for an automatically unfair reason as listed in s 187(1)(g) of the LRA or whether he was dismissed for operational requirements; was not entitled to give him an ultimatum to accept alternative employment on less favorable terms or face dismissal; the employers failed to discharge the onus of establishing that the employee was dismissed for a reason other than the transfer of business and that it was an automatically unfair dismissal

second generation contracting-out

two-phase transaction intrinsic to second generation contracting-out did constitute a transfer i.t.o. s 197

Rejected the submission that no transfer could take place in terms of s197 without prior compliance with s197(7) and held that the agreement envisaged in that section could be concluded after the transfer

S 197

Trade Union

Union constitution not allow member

JA29/2021

National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) and Others v AFGRI Animal Feeds (PTY) Ltd (JA29/2021) [2022] ZALCJHB 147 (17 June 2022)

[1] This appeal, with the leave of this Court, is against the judgment and order of the Labour Court (Mahosi J) delivered on 20 January 2021 which upheld a preliminary point raised by the respondent, Afgri Animal Feeds (Pty) Ltd. The Court found that the first appellant, the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) lacked the requisite locus standi to refer this matter and to represent the second to further appellants (the employees) in their unfair dismissal claim before the Labour Court in that they were employed in a sector which fell outside the scope of NUMSAs constitution. Costs were awarded against the appellants.

Membership outside union's constitution

Unregistered Trade Union

J256/19

Vodacom (Pty) Ltd and Others v National Association of South African Workers ('NASA') and Another (J256/19) [2019] ZALCJHB 49; (2019) 40 ILJ 1882 (LC) (4 March 2019)

Interdict unregistered union entering premises to communicate and meet with employees of contractor nature of rights infringed jurisdiction of court to entertain interdict concerning interference with property rights -requirements of final interdict met

[32] Therefore, as matters stand, the respondents cannot bypass the LRA mechanisms for achieving rights of access and convening meetings of members at the workplace of the employer by trying to directly enforce their constitutional rights to freedom of association and fair labour practices. Consequently, have no right to insist on access to the premises to communicate with Bidvest Services employees or to hold meetings with them on the premises

internal dispute

J1524/17

South African Chemical Workers' Union ('SACWU') and Another v Modise (J1524/17) [2017] ZALCJHB 265 (7 July 2017)

to interdict the unions general secretary from convening a purported meeting of the union labour court jurisdiction under s 158(1)(e)(i) confined to disputes about the interpretation and application of the constitution between union members and a union does not extend to a dispute between the union and an office bearer who is not a member

taking possession of movable property

JS964/2015

Vermaak and Another v Sea Spirit Trading 162 CC t/a Paledi Super Spar and Others (JS964/2015) [2017] ZALCJHB 34; (2017) 38 ILJ 1411 (LC) (31 January 2017)

The question is: does the perfection of a notarial bond and consequent taking of possession of movable property to realise an indebtedness constitute a transfer of a business as a going concern as contemplated in section 197 of the LRA.

[70] In my view Spar did more that to act as a creditor seeking to secure and realise indebtedness to it. If Spar simply sought to secure and realise a debt, it could have taken control over the movable property of Paledi Super Spar and Paledi Tops and could have sold or dispose of the moveable property to realise the debt. Instead, Spar took not only control over the movable property, but also of the stores and operated the stores from 1 July 2015 until April 2016, when Spar sold the businesses as going concerns.

[74]Section 197 will be triggered if a business was transferred as a going concern. That means that a business in operation is transferred to remain the same but in different hands. The sale of a business is not required by section 197, nor is it required that the transfer be a long term or permanent one. In my view the intention of the parties or the reason why a business is transferred, is immaterial and irrelevant and play no role in the objective enquiry whether a transfer as contemplated in section 197 of the Act has taken place.

Van der Velde v Business and Design Software (Pty) Ltd (2006) 27 ILJ 1738 (LC) at 1148-1149

In summary, and in an attempt to crystallize these views and to formulate a test that properly balances employer H and worker interests, the legal position when an applicant claims that a dismissal is automatically unfair because the reason for dismissal was a transfer in terms of s 197 or a reason related to it, is this:

Registration denied

union was not formed and managed by employees to regulate their relations with employers, nor did it function as a trade union in accordance with its constitution;.

term genuine; that the Registrar does not enjoy a majoritarian gatekeeper role at the registration stage and that his refusal to register the union was a misinterpretation of his authority; registration of the union was ordered.

although registration was not a sine qua non for the separate juristic personality of a union registered unions enjoy various organisational rights which were critical to a unions viability and efficacy

C491/04

Workers Union of SA v Crouse, J N.O. & The Department of Labour

Locus standi

union had failed to cite the individual employees as co-applicants

union was entitled to refer the dispute in terms of s200(1) of the LRA and that the referral was valid

Public Holidays Act 1994

Offer for re-employment

JS40/14

Truter v Heat Tech Geysers (Pty) Ltd (JS40/14) [2016] ZALCJHB 83 (2 March 2016)

Provides for a minimum number of public holidays days ; Where a public holiday falls on a Sunday, both the Sunday and the Monday constitute public holidays

Protected disclosure act

The applicant (employee) party bears the evidentiary burden in this enquiry.[The applicant (employee) party bears the evidentiary burden in this enquiry.[56]]...[87] I am satisfied that what the applicant was witnessing in the period between 29 January and 1 February 2018, from his reasonable perspective, was the committing of impropriety in contravention of the FAIS Act and its regulatory provisions...[90]...In my view, it is like selling someone elses property without their permission.

JS 751 / 18

Smyth v Anglorand Securities Ltd (JS 751 / 18) [2022] ZALCJHB 72 (28 March 2022)

(TO WHO MAKING A DISCLSURE): [51] Next, when would the disclosure be a protected disclosure? In deciding this, the Court in Palace Group Investments (Pty) Ltd and Another v Mackie[(2014) 35 ILJ 973 (LAC) at para 15.] gave the following guidance: not all disclosures are protected in the sense of protecting the employee making the disclosure from being subjected to an occupational detriment by the employer implicated in the disclosure. A protected disclosure is defined as a disclosure made to the persons/bodies mentioned in ss 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 and made in accordance with the provisions of each of such sections. In terms of s 6, for a disclosure to fall within the ambit of a protected disclosure it must have been made in good faith. It is clear that before other provisions of the PDA can come into play, the disclosure allegedly made must answer to the definition of that term as set out in the definitions section [52] Section 5 of the PDA provides that a disclosure made to a legal practitioner with the object of and in the course of obtaining legal advice is a protected disclosure. Section 6 provides for the disclosure to be made to the employer of the employee, and prescribes that the disclosure must be made in good faith and pursuant to the procedure prescribed by the employer for making such disclosure where such a procedure exists.[21] Sections 8(1)(a) and (b) provide for various prescribed bodies to which a protected disclosure can be made, namely the the Public Protector, South African Human Rights Commission, Commission for Gender Equality, Commission for the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Cultural, Religious and Linguistic Communities, Public Service Commission and the Auditor-General, provided once again that the disclosure is made in good faith.[22] Section 8(1)(c) adds the further requirements that the employee must reasonably believe that the relevant impropriety falls within any description of matters which in the ordinary course are dealt with by that person or body concerned, and that the information and any allegation contained in the disclosure are substantially true.

[55] What the above prescribed structure for making disclosures shows is that there are different considerations applicable to determining whether a disclosure qualifies as a protected disclosure, depending upon the person or body to which the disclosure has been made. As held in Tshishonga supra:[Id at para 198.]The tests are graduated proportionately to the risks of making disclosure. Thus the lowest threshold is set for disclosures to a legal adviser. Higher standards have to be met once the disclosure goes beyond the employer. The most stringent requirements have to be met if the disclosure is made public or to bodies that are not prescribed, for example the media.

(good faith): [56] However, and what is clear from all these prescripts, save of course only where the disclosure is made to a legal representative for the purposes of seeking legal advice, is the core requirement of the existence of good faith when the disclosure is made. One must however be careful not to set the bar of good faith too high, as doing so may very well defeat the purposes of what the PDA seeks to achieve, as recognized in Radebe and Another v Premier, Free State Province and Others[(2012) 33 ILJ 2353 (LAC) at para 34.]. So, it is important to decide what would constitute good faith for the purposes of protection under the PDA, which I turn to next.

[57] First, good faith, or bona fides, depending how one wants to call it, goes hand in hand with the requirement of reason to believe that the information constitutes an impropriety as defined in section 1(1) of the PDA. As said in Radebe supra:[Id at para 33. See also Tshishonga (supra) at para 186.] If the employee believes that the information is true it would fortify the reasonableness of his belief from which, in turn, his bona fides can be inferred . The Court in Radebe gave the following instructive views as to how bona fides can be inferred:[] Whilst good faith and honesty may conceivably amount to the same thing, I am of the view that a case by case approach is the proper one for a court considering these issues. Factors such as reckless abandon, malice or the presence of an ulterior motive aimed at self advancement or revenge, for instance, would lead to a conclusion of lack of good faith. A clear indicator of lack of good faith is also where disingenuity is demonstrated by reliance on fabricated information or information known by the employee to be false. The absence of these elements on the other hand is a strong indicator that the employee honestly made the disclosure wishing for action to be taken to investigate it.The Court in Radebe concluded:[27]Simply stated if an employee discloses information in good faith and reasonably believes that the information disclosed shows or tends to show that improprieties were committed or continue to be committed then the disclosure is one that is protected. The requirement of 'reason to believe' cannot be equated to personal knowledge of the information disclosed. That would set so high a standard as to frustrate the operation of the PDA. [58] It is important to appreciate that it is not necessary for the purposes of establishing good faith that it be proven that information disclosed was correct or true.[28] By definition, and in making the disclosure, the employee must only have reason to believe, not that the information is actually true, but that the information shows or tends to show that the impropriety has been or is being or may be committed in the future.[29] In applying these concepts, the Court in Baxter v Minister of Justice and Correctional Services and Others[(2020) 41 ILJ 2553 (LAC) at para 67.] held: it is important to note that the PDA does not require that the disclosures made are factually correct. The phrase tends to show in s 1 of the PDA intends that it is sufficient if the information in the disclosure is indicative of an impropriety. Likewise, the requirement that the employee merely have a reason to believe that the information points to an irregularity does not require personal knowledge of the information disclosed. That would set too high a standard frustrating the operation of the PDA. Hearsay information, depending on its nature and cogency, may provide a basis for a reasonable belief of possible irregularity.[59] Also in the above context, the Court in John v Afrox Oxygen Ltd[(2018) 39 ILJ 1278 (LAC) at para 26. The Court was referring in the quoted passage to SA Municipal Workers Union National Fund v Arbuthnot (2014) 35 ILJ 2434 (LAC) at para 15. See also para 28 of the judgment in John v Afrox where it was held: In holding that the appellant should prove the correctness of the facts for existence of the belief in order to enjoy protection, the court a quo elevated the requirement of the reasonableness of the belief to one of the accuracy of the facts upon which the belief was based. This sets a higher standard than what is required by the PDA, and such a requirement would frustrate the operation of the PDA .] held: In Arbuthnot, the court held that the enquiry is not about the reasonableness of the information, but about the reasonableness of the belief. This is so because the requirement of reasonable belief does not entail demonstrating the correctness of the information, because a belief can still be reasonable even if the information turns out to be inaccurate.[60] The fact that the information concerned may be sensitive to an employer or possibly expose it to possible reputational harm, cannot serve to strip the employee from protection in terms of the PDA. This was appreciated in Potgieter v Tubatse Ferrochrome and Others[(2014) 35 ILJ 2419 (LAC) at para 31. See also State Information Technology Agency (Pty) Ltd v Sekgobela (2012) 33 ILJ 2374 (LAC) at para 31, where the Court accepted that the legitimacy of any disclosure does not depend on how it is treated by whoever it is made to.] where the Court held:While due regard must be paid to the reputational damage that an organization may suffer as a result of disclosure of adverse information which is prejudicial to its commercial interests, I am of the view that a finding that the mere disclosure of sensitive information renders the employment relationship intolerable would, in my view, seriously erode the very protection that the abovementioned legal framework seeks to grant to whistleblowers.

(the motives of the employee): [61] Whilst it may be important to consider the motives of the employee in making the disclose, it is not necessary for the motives of the employee in making the disclosure to be as pure as the driven snow. The fact that an employee may have some ulterior motives cannot of its own scupper good faith. I venture to say that where ulterior motives or personal aspirations of the employee form the driving force behind making the disclosure, and are coupled with elements like dishonesty, corruption, false statements, and retribution, that good faith will fall by the wayside.[See Arbuthnot (supra) at para 23. In Sekgobela (supra) at para 32, it was held that: an ulterior motive such as personal antagonism which might have been the predominant purpose for making the disclosure , was incompatible with good faith. In Ngobeni v Minister of Communications and Another (2014) 35 ILJ 2506 (LC) at para 54, the Court referred to factors such as lack of honest intention, malice, ulterior motive, a quest for revenge, reckless abandon, a quest for self or others advancement, and attempts to divert attention from one's or others' wrongdoing and involvement in criminal or acts of misconduct , as negating good faith.] In short, mixed motives are not incompatible with the existence of good faith as required by the PDA. This was recognized in Baxter supra, where the Court said:[34]In any event, the fact that the appellant may have acted partly out of ulterior motive does not mean that he did not act in good faith (or acted in bad faith) by making the disclosure. Good faith must be assessed contextually on a case-by-case basis, taking account of various factors at play in the specific case. Acting with an ulterior motive is not necessarily the same as acting in bad faith. Acting in bad faith in a strict sense refers to a dishonest intention or a corrupt motive. The information in the disclosures made by the appellant was in fact true in important respects. The appellant did not deceitfully manufacture information or unreasonably exaggerate the wrongdoing that had taken place. There were real problems with the manner in which appointments were being made in the region for which Nxele was responsible. The fact that the appellant acted with some personal animosity or spite is not alone sufficient to conclude that he did not act in good faith. His earlier attempts to challenge the decisions, while somewhat tentative, and perhaps self-serving, reveal that by the time he belatedly made the disclosures (some weeks after being threatened by Nxele) he had mixed motives. In the circumstances it cannot be said that the appellant did not make the disclosures in good faith. In the result, the disclosures he made were protected disclosures in terms of the PDA [62] I do accept that the PDA cannot serve as open licence to be abused by employees in order to hide or escape their own misconduct, performance issues or other forms of serious transgressions on their part.[See Tshishonga (supra) at para 170, where it was said: Employees also have to act in the employer's best interest, to observe its right to confidentiality, to be loyal and ultimately to preserve its viability, good name and reputation . Another example can be found in Legal Aid SA v Mayisela and Others (2019) 40 ILJ 1526 (LAC) at para 63, where it was held that where an employee threatens to report the employer to authorities, this threat does not constitute the disclosure of information as contemplated by the PDA.] That is why the motives of an employee would nonetheless always be an important consideration when deciding on the issue of good faith. As held in Lephoto supra:[] the PDA was not enacted to encourage employees, whose own conduct renders them liable to dismissal, to exploit this legislation in a desperate attempt to fend off the inevitable consequences of their own actions or performance. That the PDA should be interpreted generously in order to vindicate its purpose is one thing, but in a case such as the present, where the facts are overwhelmingly in support of the conclusion that its provisions were abused, the court should have no truck with an attempt to invoke its protection.

(what the employee requires to be done in making the disclosure): [63] A further consideration relevant in assessing whether good faith exists is what the employee requires to be done in making the disclosure. For example, where the employee asks that the wrong be further investigated, or remedied, or be addressed by a responsible authority, that would an indicator of the existence of good faith.[37] It is however not a stated purpose of the PDA to ensure that the subject matter of the disclosure made be investigated or dealt with, as the PDA rather centres around the protection of the employee for making the disclosure.[City of Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality v Engineering Council of SA and Another (2010) 31 ILJ 322 (SCA) at para 33.]

(section 9 of the PDA): [65] Good faith aside, where the disclosure is made to a third party, meaning a party other then one of the parties prescribed in sections 5, 6, 7 and 8 of the PDA, there are additional qualifying requirements under section 9 of the PDA, other than the general requirements of reasonable belief and good faith in making the disclosure, for it to be protected. In these cases, the employee must establish, in sequence, that: (1) the employee reasonably believed that the information was substantially true; (2) the disclosure was not made for the purposes of personal gain;[40] (3) at least one of the conditions in section 9(2) applies;[41] and (4) it was reasonable to have made the disclosure.[See Malan v Johannesburg Philharmonic Orchestra (JA 61/11) [2013] ZALAC 24 at para 29.][66] What is immediately evident from section 9 is that there is an enhanced and double requirement of reasonableness, so to speak. First, the employee must reasonably believe that the information is substantially true, which is a higher standard than the ordinary good faith requirement of a reasonable belief that the information is true. I venture to say that in order to establish a reasonable belief that the information is substantially true, the employee must show the existence of an objective justification for his or her belief that the information is true.[43] As said in Tshishonga supra:[44] Information of quality and quantity go to determining whether the disclosure is substantially true . Second, and even if the employee has a reasonable belief that the information is substantially true, the employee must also show that it was reasonable to have made the disclosure in the first place. Thus, it follows that the employee must provide reasonable justification as to why the disclosure could not have been dealt with internally in the employer, rather than the disclosure being made to a third party.[45] It is in this context that section 9(3) provides guidance, setting out a number of considerations that can be applied to determine whether it was reasonable to make the disclosure.

(information concerned is actually true, but with an ulterior or malicious motive): [67] Interestingly however, if it is shown that the information concerned is actually true, the fact that it may have been disclosed to such a third party with an ulterior or malicious motive, would not disqualify the disclosure from still being a protected disclosure. This was recognized in Tshishonga supra where the Court held:[]A malicious motive cannot disqualify the disclosure if the information is solid. If it did, the unwelcome consequence would be that a disclosure would be unprotected even if it benefits society. Such might be the case of an accountant who out of malice discloses to SARS that his employer is evading taxes. Or, an employee of a trade union who bears a grudge against its management might blow the whistle to the registrar of trade unions that the trade union is not complying with its constitution and the LRA. A malicious motive could affect the remedy awarded to the whistle-blower. ...[94] But even if some kind of malice or ulterior motive can be attributed to the applicant, this still does not assist the respondent. Where the information disclosed is actually true, which I believe was the case in this instance, then the issue of a motive becomes largely irrelevant.

(not make the disclosure as a quid pro quo for being promised some benefit, payment, advantage or other kind of reward): [68] Finally, and as to the requirement of personal gain, the employee must not make the disclosure as a quid pro quo for being promised some benefit, payment, advantage or other kind of reward. This obviously does not include a legally prescribed benefit or reward.[47] In other words, the employee must not be in it for the money, but rather with the altruistic motivation of exposing perpetrators of maleficence in the interest of society and / or victims of such unlawful conduct.

(occupational detriment and if there is more than one reason for a dismissal): [69] Once it has been established that the employee has made a disclosure of information which qualifies as a protected disclosure under the PDA, the next step is to then determine whether the employee has been visited with an occupational detriment by his or her employer as a result of or because of making such a protected disclosure.[48] This entails the application of a causation test. In TSB Sugar supra[Id at paras 94 95. See also Lowies v University of Johannesburg (2013) 34 ILJ 3232 (LC) at para 51] the Court dealt with this consideration as follows: The phrase on account of means owing to, by reason of or because of the fact that. The phrase is used to introduce the reason or explanation for something for the purposes of the present discussion, the reason or explanation for the occupational detriment. The word partly means not completely, not solely, not entirely or not fully. A finding that an employee was subjected to an occupational detriment on account of having made a protected disclosure will be based on a conclusion that the sole or predominant reason or explanation for the occupational detriment was the protected disclosure; whereas a finding that an employee was subjected to an occupational detriment partly on account of having made a protected disclosure will be to the effect that the protected disclosure was one of more than one reason for the occupational detriment.Section 3 of the PDA thus casts the net wide. If there is more than one reason for a dismissal, the PDA will be contravened if any one of the reasons for the dismissal is the employee having made a protected disclosure. The wide scope of protection is consistent with the purposes of the PDA which addresses important constitutional values and injunctions regarding clean government and effective public service delivery.

[70] The point is that once it is shown that the protected disclosure was the main reason why the employee was dismissed, it simply does not matter if the employees dismissal may have been justified for other secondary reasons, as the employer is, by virtue of the provisions of section 187(1) of the LRA, prohibited from offering any other substantive defence to the dismissal. This was made clear in Baxter supra[50] where the Court said:Section 187(1) of the LRA lists reasons for which employees may not be dismissed (including making a protected disclosure under the PDA) and categorises such dismissals as automatically unfair. If it is proved that the employee was dismissed for any of the reasons specified in s 187(1) of the LRA, the employer cannot raise a defence based on the alleged fairness of the dismissal. The employer cannot claim that a dismissal for a proscribed reason was necessary for any other secondary reason, even if it can be argued that the dismissal was effected for a permissible reason related to the employees conduct or capacity or the employers operational requirements.[71] In determining whether the protected disclosure was the main reason for the dismissal of the employee, the well-known causation test as enunciated in SA Chemical Workers Union and Others v Afrox Ltd[51] finds application. As held in Baxter supra:[52] there may be different reasons for dismissing an employee and an employer is entitled to argue that the reason for the dismissal was not for a reason proscribed by s 187(1) of the LRA but for a fair reason based on incapacity or misconduct. The question will then trigger a causation enquiry. The essential enquiry is whether the reason for the dismissal is one proscribed by s 187(1) of the LRA, in this case the one in s 187(1)(h) of the LRA which proscribes the dismissal of an employee for making a protected disclosure

(the but for test): [72] In simple terms, this causation test involves what is in essence a two-stage enquiry.[See Baxter (supra) at paras 60 and 84; Mashaba v Telkom SA (2018) 39 ILJ 1067 (LC) at para 34.] The first part of the enquiry is to determine whether the dismissal of the employee would have taken place even if the employee did not make the protected disclosure, or in other words, the but for test. If the answer to this is yes, then the dismissal cannot be automatically unfair, because the necessary causation between the protected disclosure and the dismissal is absent. However, if the answer is no, then the second stage of the enquiry must be applied, being a determination whether the disclosure was the dominant, main, proximate or most likely cause of the dismissal.[In Independent Municipal and Allied Trade Union and Another v City of Matlosana Local Municipality and Another (2014) 35 ILJ 2459 (LC) at para 77, the Court said: Thus, what I am required to establish is the proximate cause of the disciplinary enquiry. It is clear that a disciplinary enquiry against an employee need not necessarily be the direct result of a disclosure. I propose that a useful and practical approach is to consider factors such as (i) the timing of the disciplinary enquiry; (ii) the reasons given by the employer for taking the disciplinary steps; (iii) the nature of the disclosure; (iv) and the persons responsible within the employer for taking the decisions to institute charges. See also Gallocher (supra) at para 74.] If the answer to this question is yes, then the dismissal would be automatically unfair, and if no, it would not....[116] Firstly, and when applying the but for first part of the causation test, it can easily be said that if it was not for making the disclosure, the applicant would never have been disciplined, let alone dismissed...[119] There is however a piece of evidence by Carter that in my view goes a long way towards showing that but for the disclosure, the applicant would never have been disciplined. Carter testified that when he consulted Fluxmans about the disclosure, he was asked why did he not dismiss the applicant. It is in the context of this discussion that Carter was asked by Fluxmans to collect evidence and then provide it to Fluxmans, which in my view was a deliberate stratagem to bring about the dismissal of the applicant.

[114] In sum, I conclude that the disclosure made by the applicant to the FSB on 5 February 2018, as copied to both Carter and Ma, constituted a proper and legitimate protected disclosure as contemplated by the PDA. The information disclosed qualified as information contemplated by the PDA in section 1(1) thereof. The disclosure was made in circumstances where the applicant reasonably believed the information was substantially true (the information disclosed was in fact true). The applicants conduct in making the disclosure was in good faith, and pursuant to what he saw as his obligations under the relevant applicable regulatory provisions. And finally, when applying section 9(1), the applicant has satisfied the conditions in sections 9(2)(a) and (d), the applicant obtained no benefit from the disclosure, and it was reasonable to have made the disclosure in the first place. The following dictum from the judgment in City of Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality v Engineering Council of SA and Another[(2010) 31 ILJ 322 (SCA) at para 45.], where the Court accepted a protected disclosure had been made by the employee, can equally be applied to the conduct of the applicant in casu:The effect of these provisions is that the disclosure would be protected if Mr Weyers acted in good faith; reasonably believed that the information disclosed and the allegations made by him were substantially true; was not acting for personal gain and one or other of the conditions in s 9(2)(c) and (d) was satisfied. Mr Pauw rightly conceded that the first three requirements were satisfied. In the light of the evidence summarized earlier in this judgment he could do no less. It is plain that Mr Weyers was throughout painfully aware of his professional responsibilities and of the need to provide residents of Tshwane with a safe and reliable electricity supply. His concern about the dangers arising from appointing people who, after testing, he regarded as insufficiently skilled to undertake the onerous duties attaching to a system operator position shines through each document. His bona fides and his belief in the truth of what he was saying are apparent. As this case shows he made the disclosure at considerable personal cost and not for personal gain. He acted in the discharge of what he conceived, and had been advised, was his professional duty. The disclosure was made to parties that would manifestly be interested in such disclosure.

[121] Finally, was the protected disclosure the main, dominant or proximate cause of the dismissal of the applicant, considering all the other misconduct charges. Deciding this question does entail that the substance of the other charges must be considered. Obviously, it is not for this Court to decide if a dismissal based on the other misconduct charges would be substantively fair, as only the CCMA has that jurisdiction. The assessment of the substance of the other misconduct charges is done only in the context of deciding, and putting it as simply as possible, what was the most important reason for the applicant being dismissed.

Urgent application without referring dispute to CCMA

J 1480/2021

NEHAWU obo N Phathela v Office of the Premier: Limpopo Provincial Government and Others (J 1480/2021) [2022] ZALCJHB 8 (7 February 2022)

[13] In the light of the above, this Court has no jurisdiction to grant the final order sought. The matter, if alleged to constitute an occupational detriment that arose as a result of a protected disclosure, will be deemed an unfair labour practice under section 4(2)(b) of the PDA. When read with section 191(13) of the LRA the matter must be referred to conciliation and a certificate of non-resolution must be issued before this Court can decide whether to grant the final relief sought. This is a jurisdictional prerequisite for this Court to determine an application for final relief that a disciplinary hearing constitutes a protected disclosure.

no evidence before this Court of a disclosure made in good faith

JS552/18

Josie v Amity International School and Another (JS552/18) [2021] ZALCJHB 441 (9 November 2021)

[57] Mrs. Josie has failed to prove that her dismissal is on account of her having made a protected disclosure. There is no evidence before this Court of a disclosure made in good faith by Mrs. Josie. Mrs. Josie failed to present any evidence whatsoever, regarding any bribery and corruption of Mrs. Kotze and other educators by Mrs. Mooloo or the Mooloo family. Her complaint therefore, does not fit into the definition of 'disclosure' as defined in the PDA. The evidence before this Court is that no contravention of any policy took place with regard to Miss Mooloo writing tests separately.

requirements

JS468/19

Kekana v Railway Safety Regulator (JS468/19) [2021] ZALCJHB 395 (13 October 2021)

[35]...When regard is had to the definition of a disclosure, five elements must exist, and those are: (a) disclosure of information, information being facts provided or learned about something or someone[10]; (b) the employee must believe that the disclosure is made in the public interest not self-serving interest; (c) if the employee hold such a belief, it must be held reasonably; (d) the employee must believe that the disclosure tends to show one or more of the matters listed in subparagraphs (a) (g); and lastly (e) if the employee does hold such belief, it must be reasonably held.[11] The question whether all the five elements have been established, an evaluative judgment by the Court, in the light of all the facts of the case, is required. Often time this exercised is squared up with the reason to belief requirement as set out in the section.

[42] Therefore, this Court arrives at a conclusion that the first leg of the enquiry as suggested in TSB Sugar RSA Ltd (now RCL Food Sugar Ltd) v Dorey[[2019] 40 ILJ 1224 (LAC).] has been satisfied. This Court is satisfied that Kekana made a disclosure to the CFO, Kgare, and the board member.

[48] In Qonde v Minister of Education, Science and Innovations and others[16], this Court stated that good faith means honesty or sincerity of an intention[17]. The conclusion this Court reaches is that Kekana was honest and sincere when he disclosed the information from 10 January 2018 up to and including 15 March 2018. Kekana only knew on 22 March 2018, literally few days after escalating the disclosures to the board, that he was to be disciplined.

[57] The test for determining the true reason for the dismissal was laid down in SACWU v Afrox Ltd[[1999] 20 ILJ 1718 (LAC)] and it is to first determine the factual causation by asking whether the dismissal would have occurred if Kekana had not make the protected disclosure. If the answer is yes, then the dismissal is not automatically unfair. If the answer is no, that does not immediately render the dismissal automatically unfair, the next issue is one of legal causation, namely whether such making of the disclosure was the main, dominant, proximate or the most likely cause of the dismissal.[Numsa and others v Aveng Trident Steel and another [2019] 40 ILJ 2024 (LAC) at Para 68 and Baxter supra at para 84.]

[61] In summary, for all the above reasons, this Court reaches a conclusion that Kekana made a protected disclosure and the real reason for his dismissal is that he made a protected disclosure.

[11]... whether or not an internal disciplinary proceeding is permitted to proceed in the face of a section 188A(11) referral. The first issue, though, is whether the application is urgent.

J157/21

Pedlar v Performing Arts Council of Free State (J157/21) [2021] ZALCJHB 45 (24 March 2021)