Policy Advocacy

Policy Advocacy

Environmental organizations and other stakeholders advocated for the inclusion of wetland conservation on the political agenda. They conducted research, public awareness campaigns, and lobbied policymakers to address the issue.

Issue Identification

Issue Identification

The agenda-setting stage for NAWCA began with the identification of the issue, which was the decline of wetland habitats in North America. Environmental groups, scientists, and government agencies played a significant role in raising awareness about the importance of wetlands and the need for conservation efforts.

Wetlands reduce the impacts of extreme weather such as flooding and drought by absorbing water in wet areas and recharging groundwater in dry areas. Healthy wetland ecosystems mitigate climate change by absorbing and storing carbon dioxide.

Wetland ecosystems have been diminished by development, pollution, agriculture, sea level rise, and climate change. In the 1600s, wetlands occupied 221 million acres in the United States, but by the 1980s, that was reduced to 103 million acres.

https://www.eesi.org/articles/view/federal-resilience-programs-north-american-wetlands-conservation-act

Policy Formation

Committee Review

Committee Review

Congressional committees, such as the House Committee on Natural Resources and the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, reviewed the bill and made recommendations for changes or improvements.

Debates & Amendments

Debates and Amendments

The proposed legislation went through debates and amendments in Congress. Different interest groups and political parties had their say in shaping the final bill.

Drafting Legislation

Drafting Legislation

During this stage, policymakers, often led by members of Congress, drafted the NAWCA legislation. They considered input from various stakeholders, including environmental organizations, scientists, and government agencies, to create a comprehensive bill.

Regulatory Implementation

Regulatory Implementation

Relevant government agencies, such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, developed regulations and guidelines for implementing the NAWCA and distributing funds to conservation projects. Many small grant programs have been established for its management.

https://www.fws.gov/program/north-american-wetlands-conservation

Passage of Legislation

Passage of Legislation

After the bill passed both houses of Congress, it was sent to the President for approval. Once signed into law, the NAWCA became an official policy.

Policy & Program Evaluation

Report Generation

Report Generation

Government agencies and organizations involved in NAWCA periodically generated reports to provide evidence of the program's success and challenges. These reports were used to inform future policy decisions.

Monitoring Assessment

Monitoring and Assessment

To ensure the effectiveness of NAWCA, ongoing evaluation and monitoring of wetland conservation projects were conducted. This involved assessing the impact of funded projects on wetland habitats and the populations of migratory birds.

Policy Change

Amendments & Reauthorization

Amendments and Reauthorization

NAWCA was initially passed in 1989 and has been reauthorized multiple times since then. Reauthorization typically involves Congress reviewing the existing legislation and making decisions about its continuation. During this process, lawmakers can propose amendments to the law to address new challenges, expand funding, or adjust program parameters.

Expansion

Expansion

Depending on the political climate and changing priorities, NAWCA's scope and funding levels can be expanded through legislative processes.

Recent Expansion:

The North American Wetlands Conservation Council recently announced several significant changes to the U.S. North American Wetlands Conservation Act (NAWCA) grant programs that will go into effect with the 2024 proposal cycles. These changes are intended to reduce barriers and increase participation on projects, to help build partnerships with new organizations, and to account for the increased costs of conservation.

https://acjv.org/major-changes-to-nawca-in-2023/

Sources

Policy change

Enforcement

This policy change is aimed at improving water quality and protecting aquatic ecosystems by reducing harmful discharges into the nation's water bodies.

changes is to enforce mechanisms to ensure compliance with permit conditions, and non-compliance resulting in penalties, fines, and other enforcement actions to deter violation.

This policy change also provides a structured framework for controlling pollutant discharges, setting clear standards, and enforcing compliance.

changes and amendments

Setting new discharge standards for toxic pollutants.

Establishing a phased approach to controlling industrial pollutants.

Expanding the NPDES permitting program to cover more types of dischargers.

Enhancing federal enforcement authority.

Policy and Program Evaluation

Water Quality Assessment

Evaluators assess water quality data to determine whether water bodies are subject to the Clean Water Act regulation to see if there is any improvement over time.

Evaluate and analyze data on various pollutants, nutrient levels, and other water quality.

Recommendations

Based on evaluation findings, experts may make recommendations of improvement to the Clean Water Act or its associate program

These recommendations can inform future legislative or regulatory actions.

Stakeholder Feedback

Evaluators gather feedback from various stakeholders, including industry representatives, environmental organizations, state and local gov't, and the general public

This feedback provides insight into the Act implementation and effectiveness.

Stakeholder organizations often work with states, territories, and authorized tribes to monitor and report on the condition of local waters.

https://www.epa.gov/standards-water-body-health/partners-you-can-work-protect-water-quality#:~:text=Stakeholder%20organizations%20may%20include%20trade,Organizing%20volunteer%20efforts

Congressional Approval

Clean water act went throught legislative process in Congress, where it was debated, amended, and eventually passed by both the house od Rep. and the Senate. This legislative approval provided the policy with legal authority and legitimacy as federal law.

Public Awareness and Support

Public became more aware and concerned for water pollution which resulted in Clean Water Act to gain the legitimacy.

Program effect- The publication of "Silent Spring" drew attention to the need for stronger water quality regulation.

Drafting the Legislation

Drafting the Clean Water Act involved crafting the language, provisions, and goals of the bill. This process included consultations with legal experts, environmental experts, and policymakers.

Research and Monitoring

The Clean Water Act authorized funding for research and monitoring of water quality and pollution control technologies. This helped gather data to inform regulatory decisions and improve pollution control practices.

Water Quality Standards

The Act authorized the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to set water quality standards for pollutants in surface waters. States were encouraged to adopt these standards and establish their own water quality criteria.

EPA has implemented pollution control programs such as setting wastewater standards for industry.

https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-clean-water-act

Public Awareness and Concern

Growing public concern about water pollution, low water quality, and environmental issues

Driven by a combination of environmental concerns and public awareness

Before the agenda setting, farmers began using new chemical pesticides against the armies of insects/various pests that invaded their crops and threatened their harvests. By the late 1960s, American farmers were applying more than one billion pounds of these pesticides a year.

Rachel Carson's "Silent Spring" raised awareness about the harmful effects of pesticides and other pollutants on the environment, including water bodies

https://billofrightsinstitute.org/essays/rachel-carson-and-silent-spring

Recovery & Penalties

The act also created recovery plans for species, especially ones that are listed as threatened or endangered. This includes strategies for recovering and goals on how to get species off the threatened lists.

The act also states a list of enforcements and fines for violations of the act. Ranges from hundreds to thousands of pounds and in some cases imprisonment.

Other Changes

The act also made these changes:

- Designation of National Parks and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs)

- Protection of a wide range of plant and animal species, including mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Control of invasive species

- Protections for hedgerows, which are important wildlife habitats and landscape features in the UK

- Measures to control the use of pesticides and poisons to protect wildlife

- Prevention of the illegal trade in wildlife and their products

Protected Areas (SSSIs)

This act allowed for the authorities to designate Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs) in order to protect species and their habitats.

Overall, the act allowed for protection of native and migratory bird species. Under this act it is illegal to intentionally kill, injure, take bird species, and damage/destroy nests.

Parliamentary Approval

The most crucial stage of the policy legitimization of the act was approval by the UK Parliament. It gave the act the legal authority needed for full implementation.

In the Parliament, the act received cross-party support. This showed to the public that this was an important issue and wasn't divided by the multi-party system.

Drafting

The main people drafting the legislation were government officials and legal experts. They took into account the opinions and research of all the parties.

This step involved translating policy objectives into specific legal provisions.

The draft of the legislation was introduced to the UK Parliament as a Bill. It went through the House of Commons and House of Lords. Amendments were made through many readings, debates, and committee discussions.

Engagement from Parties

Stakeholders like landowners, conservation organizations, and the government were all consulted during the formation of the Wildlife and Countryside Act of 1981.

Scientists provided expertise and research to back up the human impact on ecosystems and inform the policy formation process.

International Commitments like CITES influenced the formulation of this policy.

Government Committees

The UK had appointed government committees and groups to go out and assess the current state of wildlife and conservation in the country.

Reports came out like the "Better Planning for Wildlife" paper in 1977 which noted the flaws in existing legislation and recommended new condensed laws.

Pressure & Research

Organizations like the Royal Society for Protection of Birds and Wildlife Trusts advocated for stronger legal protections of species and habitats.

Lobbying increased awareness towards the government and also for the general public to understand the issues that were going on.

Scientists in the UK were also presenting their evidence from research and studies to have stronger legal safeguards. This shaped the agenda for this legislative act.

Before the Act

Before this Act was put into place the United Kingdom had only a few, dispersed wildlife protection laws in effect.

The environmentalists, conservationists, and the public were beginning to grow concerned about the country's native wildlife and habitats. There was a decline in species populations due to development and changing of land usage.

In the 1970s/80s there was an influx of awareness for biodiversity conservation. Driven by high-profile environmental campaigns, documentaries, and public interest in nature.

Agenda Setting

Policy Formulation

Policy Legitimization

Policy & Program Evaluation

Review Process

The act is regularly reviewed by the policymakers and conservation agencies around the UK. They make sure that the enforcements are being enacted and address any challenges that may arise.

Scientific research that is still ongoing contributes feedback into changing or reviewing pieces of the act's outline. Making sure that the health of species is okay, habitat qualities are being upheld, and impacts of conservation measures.

Based upon evaluations the policymakers do have the right to amend the act in order to strengthen, protect, and conserve UK's environment.

Implementation

After the act was officially a law, agencies like the Natural England & Natural Resource Wales had the responsibility of implementing the act's provisions.

They created an implementation plan to help with the guidance of the execution. This included facilitating species & habitat protection and the access to UK's countryside.

Policy Change

"The Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 is the primary legislation which protects animals, plants and habitats in the UK"

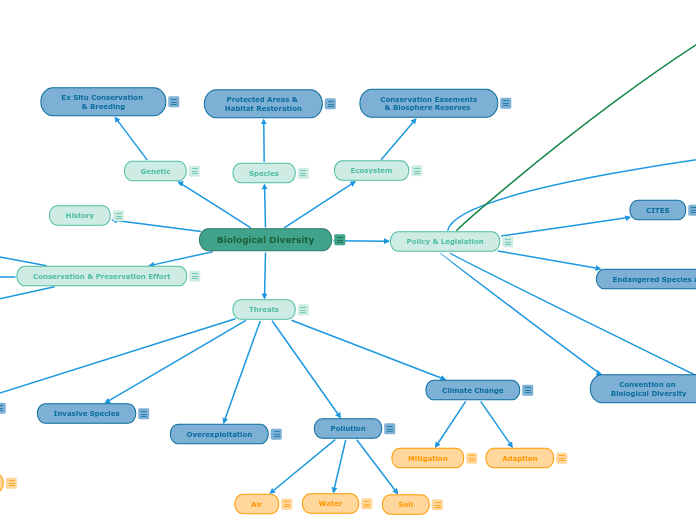

Biological Diversity

Biodiversity

Biological diversity is the variety of life forms and living organisms on Earth. It includes the diversity of plants and animals as well as the ecosystems.

Conservation & Preservation Effort

Conservation and preservation efforts in biodiversity are essential to protect the Earth's rich variety of species, ecosystems, and genetic diversity. These efforts aim to prevent species extinction, maintain ecosystem functions, and ensure that future generations can benefit from the biological diversity of our planet.

Marine Sanctuaries

Marine Sanctuaries

Marine sanctuaries, also known as marine protected areas (MPAs), are designated areas of the ocean that are legally protected to conserve and protect marine ecosystems, biodiversity, and cultural heritage. These areas are established to restrict or regulate human activities that may harm the marine environment. Here are some examples of notable marine sanctuaries from around the world:

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (Australia): The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park is one of the largest and most famous marine sanctuaries in the world. It spans over 1,400 miles along the coast of Queensland, Australia, and is home to diverse coral reefs, marine life, and ecosystems.

Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (USA): Located in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, this monument is one of the world's largest marine protected areas. It encompasses over 580,000 square miles of ocean and is home to unique and endangered species.

Galápagos Marine Reserve (Ecuador): Surrounding the Galápagos Islands, this marine reserve is renowned for its biodiversity, including marine iguanas, giant tortoises, and unique fish species. It's a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary (USA): Situated off the coast of California, this sanctuary protects a rich and diverse marine environment, including kelp forests, deep-sea canyons, and an array of marine species.

Chagos Marine Protected Area (UK): Located in the Indian Ocean, this MPA is one of the largest no-take marine reserves. It protects coral reefs, seabird colonies, and important shark and turtle populations.

Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park (Philippines): This UNESCO World Heritage site in the Sulu Sea is home to extensive coral reefs and a remarkable diversity of marine life. It is a no-take zone to protect its pristine condition.

Aldabra Atoll (Seychelles): This remote atoll in the Indian Ocean is one of the largest raised coral atolls in the world. It is home to giant tortoises, unique bird species, and diverse marine life.

Komodo National Park (Indonesia): Famous for its Komodo dragons, this park also protects the marine environment around the islands. It's known for its coral reefs, sharks, and manta rays.

Revillagigedo Archipelago National Park (Mexico): Located in the eastern Pacific Ocean, this marine sanctuary is known for its stunning underwater biodiversity, including large schools of fish and sharks.

Sian Ka'an Biosphere Reserve (Mexico): This UNESCO World Heritage site includes both terrestrial and marine protected areas in the Caribbean. It protects seagrass beds, coral reefs, and numerous marine species.

Wildlife Reserves

Wildlife Reserves

Area of land set aside and protected for the conservation and preservation of wildlife and their natural habitats. These areas are typically designated and managed by government agencies, conservation organizations, or private entities with the primary goal of protecting the native flora and fauna from human activities that could harm them, such as habitat destruction, poaching, or pollution.

National Parks

National Parks

Marine sanctuaries, also known as marine protected areas (MPAs), are designated areas of the ocean that are legally protected to conserve and protect marine ecosystems, biodiversity, and cultural heritage. These areas are established to restrict or regulate human activities that may harm the marine environment. Here are some examples of notable marine sanctuaries from around the world:

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (Australia): The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park is one of the largest and most famous marine sanctuaries in the world. It spans over 1,400 miles along the coast of Queensland, Australia, and is home to diverse coral reefs, marine life, and ecosystems.

Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (USA): Located in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, this monument is one of the world's largest marine protected areas. It encompasses over 580,000 square miles of ocean and is home to unique and endangered species.

Galápagos Marine Reserve (Ecuador): Surrounding the Galápagos Islands, this marine reserve is renowned for its biodiversity, including marine iguanas, giant tortoises, and unique fish species. It's a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary (USA): Situated off the coast of California, this sanctuary protects a rich and diverse marine environment, including kelp forests, deep-sea canyons, and an array of marine species.

Chagos Marine Protected Area (UK): Located in the Indian Ocean, this MPA is one of the largest no-take marine reserves. It protects coral reefs, seabird colonies, and important shark and turtle populations.

Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park (Philippines): This UNESCO World Heritage site in the Sulu Sea is home to extensive coral reefs and a remarkable diversity of marine life. It is a no-take zone to protect its pristine condition.

Aldabra Atoll (Seychelles): This remote atoll in the Indian Ocean is one of the largest raised coral atolls in the world. It is home to giant tortoises, unique bird species, and diverse marine life.

Komodo National Park (Indonesia): Famous for its Komodo dragons, this park also protects the marine environment around the islands. It's known for its coral reefs, sharks, and manta rays.

Revillagigedo Archipelago National Park (Mexico): Located in the eastern Pacific Ocean, this marine sanctuary is known for its stunning underwater biodiversity, including large schools of fish and sharks.

Sian Ka'an Biosphere Reserve (Mexico): This UNESCO World Heritage site includes both terrestrial and marine protected areas in the Caribbean. It protects seagrass beds, coral reefs, and numerous marine species

Policy & Legislation

Policy and legislation play a critical role in biodiversity conservation and the protection of ecosystems and species. These legal frameworks provide the rules, regulations, and guidance needed to manage and preserve biodiversity.

Clean Water Act of 1972

The goal is to regulate and maintain the quality of the nation's water resources.

Played a significant role in reducing water pollution in the United States, improving water quality, and protecting aquatic ecosystems and public health.

The Wildlife and Countryside Act

The North American Wetlands

Conservation Act

The North American Wetlands Conservation Act

Passed in 1989, NAWCA is a U.S. federal legislation designed to provide funding for the conservation and restoration of wetland habitats across North America. (administered by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service)

Purpose:

- to protect, enhance, restore, and manage an appropriate distribution and diversity of wetland ecosystems and habitats associated with wetland ecosystems and other fish and wildlife in North America

- to maintain current or improved distributions of wetland associated migratory bird populations

- to sustain an abundance of waterfowl and other wetland associated migratory birds consistent with the goals of the North American Waterfowl Management Plan, the United States Shorebird Conservation Plan, the North American Waterbird Conservation Plan, the Partners In Flight Conservation Plans, and the international obligations contained in the migratory bird treaties and conventions and other agreements with Canada, Mexico, and other countries.

Since its establishment, the NAWCA has provided grants for over 3,000 projects in all 50 states, Canada, Mexico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico, resulting in the protection of over 32 million acres. The program creates nearly 7,500 new jobs annually and has translated $1.6 billion in federal funds to more than $4.6 billion in matching grants from partner organizations for conservation projects.

https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2017-title16/pdf/USCODE-2017-title16-chap64-sec4401.pdf

https://www.eesi.org/articles/view/federal-resilience-programs-north-american-wetlands-conservation-act

CITES

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora- international agreement aimed at ensuring that international trade in wild animals and plants does not threaten their survival.

Convention on

Biological Diversity

Convention on Biological Diversity

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) is an international treaty aimed at addressing the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components, and the equitable sharing of benefits derived from genetic resources. The CBD was adopted at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1992, and it entered into force on December 29, 1993. Here are some key points about the Convention on Biological Diversity:

Objectives:

Conservation of Biodiversity: The primary goal of the CBD is the conservation of biological diversity, including ecosystems, species, and genetic resources, at local, national, and global levels.

Sustainable Use: The CBD promotes the sustainable use of biological resources to meet current and future human needs while maintaining the capacity of ecosystems to support biodiversity.

Equitable Benefit Sharing: The CBD emphasizes the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the use of genetic resources, with a particular focus on benefiting indigenous and local communities.

Key Provisions and Agreements:

National Strategies and Action Plans: Parties to the CBD are encouraged to develop and implement national strategies and action plans for biodiversity conservation.

Protected Areas: Parties are encouraged to establish and manage protected areas and conserve ecosystems that are important for biodiversity.

Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS) Protocol: The Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization is a supplementary agreement to the CBD, addressing issues related to access to genetic resources and the sharing of benefits derived from their utilization.

Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety: This protocol addresses the safe handling, transport, and use of living modified organisms (LMOs) resulting from modern biotechnology that may have adverse effects on biodiversity.

Conference of the Parties (COP):

The CBD operates through its governing body, the Conference of the Parties (COP), which meets regularly to review progress, negotiate agreements, and make decisions on matters related to biodiversity conservation.

Achievements and Challenges:

The CBD has played a pivotal role in raising awareness about the importance of biodiversity and has led to the establishment of protected areas and conservation initiatives worldwide. However, challenges remain in achieving its ambitious goals, particularly in the face of ongoing biodiversity loss and habitat degradation.

Endangered Species Act

Endangered Species Act

The Endangered Species Act (ESA) is a federal law in the United States that was enacted in 1973 to protect and conserve threatened and endangered species and their habitats. The primary purpose of the ESA is to prevent the extinction of these species and promote their recovery to the point where they are no longer at risk of extinction. Here are key aspects of the Endangered Species Act:

Listing of Species:

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) are responsible for identifying and listing species as "endangered" or "threatened" based on scientific assessments of their population status and habitat conditions.

Critical Habitat Designation:

When a species is listed, critical habitat may also be designated. This is the specific geographic area considered essential for the conservation of the species.

Protections for Listed Species:

Once a species is listed as endangered or threatened, it is afforded various legal protections. These include prohibitions on harming, harassing, or killing listed species, as well as restrictions on activities that could adversely affect their habitats.

Recovery Plans:

Federal agencies are required to develop recovery plans for each listed species. These plans outline the actions necessary for the species' recovery and delisting.

Consultation and Habitat Conservation Plans:

Federal agencies must consult with FWS or NOAA to ensure that any actions they undertake do not jeopardize the continued existence of listed species. In some cases, agencies may develop Habitat Conservation Plans to minimize impacts while allowing certain activities to proceed.

Penalties and Enforcement:

Violations of the ESA can result in penalties and legal actions. It is illegal to harm, harass, or kill listed species, trade in products made from them, or damage their critical habitats.

Citizen Suit Provisions:

The ESA includes provisions that allow citizens and organizations to file lawsuits against the government or others for failing to comply with the law's requirements.

International Cooperation:

The ESA also supports international efforts to conserve endangered and threatened species through agreements and programs.

History

History of Biological Diversity

The history of biological diversity in policy is marked by the recognition of the importance of conserving and sustainably managing the Earth's biodiversity. A brief overview of key milestones in the development of biodiversity policy:

- Early Conservation Efforts (Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries): The concept of conservation and protection of natural resources began to gain momentum in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Prominent figures like Theodore Roosevelt in the United States and Richard St. Barbe Baker in the United Kingdom advocated for the preservation of natural areas and wildlife.

- Formation of National Parks (Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries): The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the establishment of the world's first national parks, such as Yellowstone National Park in the United States (1872) and Banff National Park in Canada (1885). These protected areas served as models for future conservation efforts.

- Creation of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (1948): The IUCN, founded in 1948, is one of the world's oldest and most influential organizations dedicated to conservation. It plays a crucial role in assessing the conservation status of species, developing conservation policies, and promoting sustainable practices.

- The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) (1973): CITES is an international treaty aimed at ensuring that international trade in wild animals and plants does not threaten their survival. It regulates and monitors the international trade of species listed under its appendices

Throughout history, the recognition of the intrinsic value of biodiversity, its importance for ecosystem services, and its contribution to human well-being has grown. Biodiversity policy has evolved to address the increasing threats to ecosystems and species, emphasizing the need for international cooperation and sustainable practices to protect and conserve biological diversity.

Threats

Threats to Biodiversity

Biological diversity, or biodiversity, faces a range of threats primarily due to human activities and natural processes. The main threats include but are not limited to habitat loss, overexploitation, pollution, climate change, and invasive species.

Pollution

Threats of Pollution on Biodiversity

Toxic Effects on Organisms: Pollution introduces harmful chemicals and substances into ecosystems, leading to direct toxicity to organisms. Many pollutants, including heavy metals, pesticides, and industrial chemicals, can harm or kill wildlife and aquatic organisms.

Bioaccumulation: Some pollutants, particularly persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and heavy metals, accumulate in organisms over time through the food chain. Apex predators or humans at the top of the food chain can accumulate high levels of these toxins, leading to health problems and population declines.

Loss of Biodiversity in Aquatic Ecosystems: Water pollution, especially from chemicals like nitrogen and phosphorus, can lead to nutrient enrichment and eutrophication in aquatic ecosystems. This can result in harmful algal blooms, oxygen depletion, and the decline of fish and other aquatic species.

Altered Reproduction and Development: Some pollutants can disrupt the reproductive and developmental processes of species. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), for example, can affect the reproductive success and survival of wildlife.

Changes in Species Composition: Pollution can favor pollution-tolerant species over sensitive ones, leading to shifts in species composition. This can result in reduced biodiversity and ecosystem resilience.

Habitat Degradation: Pollution can contribute to the degradation of natural habitats, affecting the health and survival of species dependent on those habitats.

For example, soil pollution can harm beneficial soil microorganisms that play crucial roles in nutrient cycling and plant health.

Microplastic Pollution: The proliferation of microplastics in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems poses a growing threat to biodiversity. Microplastics can be ingested by a wide range of species, potentially leading to physical harm and the transfer of pollutants.

Global Implications: Air pollution, including greenhouse gases, contributes to climate change, which in turn affects biodiversity worldwide. Climate change disrupts habitats, shifts species distributions, and exacerbates the challenges faced by biodiversity.

Economic Costs: Pollution can have significant economic impacts, affecting industries like agriculture, fisheries, and tourism. Efforts to control pollution and restore ecosystems can also be costly.

Cumulative Effects: Multiple forms of pollution often coexist and interact, creating cumulative effects that can be more detrimental than individual pollutants.

Soil

Threats of Soil Pollution on Biodiversity

Reduced Soil Fertility: Soil pollution from chemicals like pesticides, herbicides, and heavy metals can decrease soil fertility. This affects the growth of plants and the availability of food resources for herbivores.

Impact on Microorganisms: Soil pollution can harm beneficial soil microorganisms that play crucial roles in nutrient cycling and plant health. This can lead to disruptions in ecosystem functioning.

Plant Toxicity: Contaminated soils can lead to the uptake of pollutants by plants. These plants can then become toxic to herbivores, impacting the health and reproduction of herbivore populations.

Habitat Degradation: Soil pollution can reduce the suitability of habitats for many organisms, including burrowing animals, microorganisms, and plants. This can lead to shifts in species composition and reduced biodiversity.

Water

Threats of Water Pollution on Biodiversity

Toxic Contaminants: Water pollution introduces a variety of toxic substances, such as heavy metals, pesticides, industrial chemicals, and pharmaceuticals, into aquatic environments. These contaminants can be lethal or cause sublethal effects in aquatic organisms, including fish, amphibians, and invertebrates.

Bioaccumulation: Some pollutants can accumulate in organisms over time, a process known as bioaccumulation. Predatory species at the top of the food chain, like apex predators or humans, can accumulate high levels of toxins, leading to health problems and population declines.

Altered Water Chemistry: Water pollution can disrupt the chemical composition of aquatic ecosystems, affecting pH levels and nutrient balances. This can harm aquatic plants, invertebrates, and fish, disrupting food webs.

Habitat Destruction: Polluted water bodies may become unsuitable for many species due to the degradation of aquatic habitats. This leads to reduced biodiversity in affected areas.

Air

Threats of Air Pollution on Biodiversity

Acid Rain: Air pollution from sulfur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) can lead to acid rain when these pollutants combine with water vapor in the atmosphere. Acid rain can damage terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, affecting soil pH and harming plants and aquatic organisms.

Respiratory Issues: Airborne pollutants, including particulate matter and ozone, can harm wildlife, particularly species with sensitive respiratory systems. For example, birds and mammals may suffer from reduced lung function and impaired reproduction.

Habitat Degradation: Air pollution can contribute to the degradation of natural habitats, affecting the health and survival of species dependent on those habitats. Forests, for instance, are vulnerable to air pollutants that can harm or kill trees and understory vegetation.

Plant Damage: High concentrations of air pollutants can damage plant foliage, reducing the quality and quantity of food sources for herbivores. This can have cascading effects on herbivore populations and their predators.

Overexploitation

Threats of Overexploitation on Biodiversity

Population Declines: Overexploitation can lead to the depletion of populations of species that are targeted for harvest. This can result in declines or even extinctions of these species. For example, overfishing has caused significant declines in many marine fish species.

Altered Ecosystems: The removal of certain species from ecosystems can disrupt ecological interactions and lead to imbalances within ecosystems. This can affect the abundance and distribution of other species, leading to shifts in species composition and potential extinctions.

Genetic Diversity Reduction: Overharvesting can reduce genetic diversity within populations as individuals with certain traits are selectively removed. Reduced genetic diversity can make species more vulnerable to environmental changes and less capable of adapting to new conditions.

Secondary Effects: The depletion of one species through overexploitation can have cascading effects on other species that depend on it for food or other ecological roles. For instance, the overharvesting of prey species can lead to declines in their predators.

Illegal Trade: Overexploitation often drives illegal trade in wildlife and their products, which can further exacerbate population declines and biodiversity loss. This illegal trade is a major driver of species endangerment and extinction.

Habitat Destruction: Some forms of overexploitation, such as deforestation for timber extraction or agricultural expansion, can result in habitat destruction, which directly impacts the biodiversity of the affected areas.

Economic and Social Consequences: Overexploitation can have economic and social consequences, particularly for communities that rely on natural resources for their livelihoods. Unsustainable harvesting can lead to the collapse of resource-based industries and the loss of jobs.

Climate Change

Threats of Climate Change on Biodiversity

Habitat Alteration and Loss: Rising temperatures and changing precipitation patterns can lead to shifts in habitat suitability. Some species may find their current habitats becoming less hospitable, while others may benefit from the changes. Alpine ecosystems, polar regions, and coral reefs are particularly vulnerable to habitat alteration or loss due to climate change.

Species Range Shifts: Many species are already moving to higher latitudes or altitudes in response to warming temperatures. This shift can disrupt existing ecological interactions and create novel ones. Some species may not be able to migrate fast enough, potentially leading to local extinctions.

Altered Phenology: Climate change can affect the timing of key life events for plants and animals, such as flowering, breeding, and migration. These shifts can disrupt the synchronization of species interactions, such as pollination and predator-prey relationships.

Ocean Acidification: The absorption of excess atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) by the oceans leads to ocean acidification. Acidic waters can harm marine organisms with calcium carbonate shells or skeletons, including corals, mollusks, and some plankton species. Disruptions in marine food webs and the loss of coral reefs can have cascading effects on biodiversity.

Extreme Weather Events: More frequent and severe extreme weather events, such as hurricanes, droughts, and wildfires, can directly harm species and ecosystems.

Populations that are already vulnerable may be pushed to the brink by such events.

Disruption of Ecological Relationships: Changes in temperature and precipitation can disrupt the timing and distribution of resources, affecting the availability of food and shelter for species. For example, shifts in temperature can alter the distribution of prey and predators, potentially leading to imbalances in ecosystems.

Invasive Species and Diseases: Climate change can create new opportunities for invasive species to establish themselves in previously unsuitable areas. Warmer temperatures can also promote the proliferation of disease vectors, increasing the risk of disease outbreaks among wildlife.

Sea Level Rise: Rising sea levels threaten coastal ecosystems, including estuaries, marshes, and mangroves, which are vital for many species. Habitat loss due to sea level rise can lead to the displacement of species and increased competition for limited resources.

Feedback Loops: Climate change can trigger feedback loops, exacerbating its own impacts. For example, thawing permafrost releases methane, a potent greenhouse gas, which further contributes to global warming.

Adaption

Adaption in Climate Change:

Habitat protection and restoration, translocation and assisted migrations, in situ conservation, ex situ conservation, community engagement and sustainable practices, ecosystem-based adaption, international collaboration, climate-resilient farms and fisheries, and educational outreach.

Mitigation

Mitigation and Climate Change:

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions, conservation and restoration of natural ecosystems, sustainable land use and agriculture, protected areas and wildlife corridors, climate-resilient conservation planning, invasive species management, community-based conservation, research and monitoring, and global collaboration.

Invasive Species

Threats of Invasive Species on Biodiversity

Competition for Resources: Invasive species often outcompete native species for essential resources like food, water, and shelter. This competition can lead to a decline in native populations, reducing the overall biodiversity of an ecosystem.

Predation and Herbivory:Invasive predators or herbivores can have a devastating impact on native species that have not evolved defenses against them. Predation by invasive species can lead to the decline or extinction of vulnerable native species.

Altered Ecosystem Dynamics:Invasive species can disrupt existing ecological relationships and food webs. This disruption can have cascading effects on multiple species within an ecosystem.

Habitat Modification: Some invasive species modify habitats by changing soil composition, altering vegetation, or increasing nutrient levels. These modifications can make the habitat less suitable for native species, further reducing biodiversity.

Disease Vectors:Invasive species, such as certain mosquitoes or ticks, can serve as vectors for diseases that affect both wildlife and humans. Disease outbreaks can have devastating consequences for native species populations.

Genetic Pollution:Interspecies hybridization between invasive and native species can occur, leading to genetic pollution. This dilution of native gene pools can threaten the genetic integrity and uniqueness of native populations.

Displacement of Native Species: As invasive species proliferate, they can displace native species from their historical habitats. This displacement can lead to range contractions and local extinctions of native species.

Resilience Reduction: Invasive species can reduce the resilience of ecosystems to environmental stressors, making native species more vulnerable to other threats, such as climate change.

Economic Costs: Invasive species can have significant economic impacts, affecting industries like agriculture, forestry, and fisheries. Efforts to control or eradicate invasive species can also be costly.

Globalization and Human Activities:

The globalization of trade and travel has accelerated the spread of invasive species.

Human activities, such as the release of non-native species, unintentional transport of invasive organisms, and habitat modification, contribute to the problem.

Habitat Loss

Threats of Habitat Loss on Biodiversity

Loss of Species and Populations: When habitats are destroyed or converted for agriculture, urban development, or infrastructure projects, the species that depend on those habitats lose their homes. Some species may not survive the immediate destruction of their habitat, leading to local extinctions.

Fragmentation of Habitats: Habitat loss often results in fragmented landscapes where isolated habitat patches are separated by human-modified areas. This fragmentation can hinder the movement of species, reducing gene flow, and making populations more vulnerable to genetic isolation and inbreeding.

Altered Ecological Relationships: Habitat loss can disrupt existing ecological relationships, including predator-prey dynamics, competition, and mutualistic interactions.

These disruptions can lead to imbalances in ecosystems and the decline of species dependent on those relationships.

Reduction in Biodiversity: As natural habitats are lost or modified, the overall biodiversity of an area decreases.

Biodiversity loss can occur at multiple levels, including genetic diversity within species, species diversity within ecosystems, and ecosystem diversity at the landscape scale.

Specialist Species Vulnerability: Species with specialized habitat requirements, often referred to as habitat specialists, are particularly vulnerable to habitat loss. These species have limited ability to adapt to changing environments or to use alternative habitats.

Impacts on Ecosystem Services: Habitats provide essential ecosystem services such as clean water, air purification, pollination, and climate regulation. The loss of these services can have wide-ranging effects on human well-being and biodiversity.

Secondary Threats: Habitat loss often brings secondary threats, including increased predation, exposure to invasive species, and greater susceptibility to diseases. These additional pressures can compound the negative effects of habitat loss on native species.

Cumulative Effects: Habitat loss can be cumulative, meaning that over time, repeated small-scale losses add up to significant overall loss. This cumulative impact can be especially harmful to species that require larger, intact habitats for their survival.

Global Scale Effects: Habitat loss is a global phenomenon and contributes to the reduction of biodiversity at a planetary scale. The loss of habitat types like rainforests, wetlands, and coral reefs has implications for biodiversity worldwide.

Efforts to address habitat loss and its impact on biodiversity include the establishment of protected areas, habitat restoration, sustainable land use practices, and conservation policies that promote the preservation of critical habitats. These measures aim to mitigate the loss of biodiversity by preserving and restoring the habitats essential for the survival of countless species.

Deforestation

Threats of Deforestation on Biodiversity

Direct Habitat Destruction: The most immediate and visible impact of deforestation is the destruction of forest habitats. This can result in the loss of crucial habitats for countless plant and animal species, including many that are endemic or endangered.

Species Extinction: As forests are cleared, many species, especially those with specialized habitat requirements, may face local extinctions or become globally extinct. Deforestation is a leading cause of species endangerment and extinction.

Fragmentation: Deforestation often leads to habitat fragmentation, where remaining forest patches become isolated from one another. Fragmentation disrupts the movements and gene flow of species, making it harder for them to adapt and persist.

Altered Ecosystem Functions: Forests provide essential ecosystem services, including carbon sequestration, water purification, and maintenance of nutrient cycles. Deforestation disrupts these functions, with consequences for both ecosystems and human societies.

Loss of Genetic Diversity: Populations in fragmented forests may experience reduced genetic diversity, which can make them less resilient to environmental changes, diseases, and other stressors.

Climate Change: Deforestation contributes to climate change by releasing stored carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Climate change, in turn, affects the distribution and behavior of species and can exacerbate biodiversity loss.

Invasive Species: Cleared areas are often susceptible to colonization by invasive species, which can outcompete native species and disrupt ecological interactions.

Disruption of Indigenous and Local Communities: Indigenous and local communities that depend on forests for their livelihoods are affected by deforestation. Their traditional knowledge and cultural practices may also be lost.

Loss of Biodiversity Hotspots: Many regions with high levels of biodiversity, such as tropical rainforests, are vulnerable to deforestation. These areas are often considered biodiversity hotspots, making their conservation particularly critical.

Agricultural Expansion

Threats of Agriculture Expansion on Biodiversity

Direct Habitat Conversion: The clearing of land for agriculture typically involves the removal of native vegetation. This direct conversion of natural habitats into agricultural fields can result in the immediate loss of habitats for numerous plant and animal species.

Fragmentation: Agricultural expansion often leads to the fragmentation of natural landscapes, as remaining patches of habitat become isolated from one another by fields, roads, and infrastructure. Fragmentation can hinder the movement of species, disrupt ecological interactions, and reduce genetic diversity within populations.

Loss of Keystone Species: Many ecosystems depend on "keystone species" that play crucial roles in maintaining ecological balance. Agricultural expansion can lead to the loss of these keystone species, which can trigger cascading ecological impacts.

Reduction in Species Diversity: As natural habitats are converted into monoculture or simplified agricultural landscapes, the diversity of plant and animal species within those areas typically decreases. This can result in local extinctions and a reduction in overall species diversity.

Habitat Specialization: Some species are highly specialized and can only survive in specific habitats. The loss of these habitats due to agricultural expansion can lead to the decline or extinction of these specialized species.

Water Pollution and Habitat Degradation: Intensive agriculture often involves the use of fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides, which can lead to water pollution and soil degradation. These impacts can harm aquatic ecosystems and the species that rely on them.

Altered Hydrology: The drainage of wetlands for agriculture and the alteration of natural water flows can have detrimental effects on aquatic ecosystems, reducing the availability of crucial habitat for many species.

Global Implications: Habitat loss through agricultural expansion is not limited to local or regional impacts. It contributes to the loss of globally significant ecosystems, such as tropical rainforests and wetlands, which host a substantial portion of the world's biodiversity.

Urbanization

Threats of Urbanization on Biodiversity

Direct Habitat Conversion: The most immediate and obvious impact of urbanization is the direct conversion of natural habitats into built environments, including residential, commercial, and industrial areas. This often involves the clearing of forests, wetlands, grasslands, and other natural landscapes.

Fragmentation: Urbanization typically leads to habitat fragmentation, where natural areas become isolated patches surrounded by urban infrastructure. Fragmentation disrupts species' movements, gene flow, and ecological interactions, making it difficult for many species to survive and thrive.

Loss of Native Flora and Fauna: The destruction of natural habitats often results in the loss of native plant and animal species. Species that are unable to adapt to urban environments may face local extinctions.

Altered Ecosystem Functions: Urbanization can alter ecosystem functions, such as nutrient cycling, water purification, and pollination. These changes can have cascading effects on the composition and health of ecosystems.

Introduction of Invasive Species: Urban areas often serve as hubs for the introduction and spread of invasive species, which can outcompete native species and disrupt local ecosystems.

Pollution and Habitat Degradation: Urbanization is associated with increased pollution, including air pollution, water pollution, and soil contamination. These pollutants can harm wildlife and aquatic species and degrade the quality of remaining habitats.

Increased Human-Wildlife Conflicts: As natural habitats shrink, some wildlife species may venture into urban areas in search of food and shelter, leading to conflicts with humans and potentially endangering both wildlife and people.

Loss of Biodiversity Hotspots: Many regions with high biodiversity, including tropical forests and coastal ecosystems, are vulnerable to urbanization. This threatens globally significant biodiversity hotspots.

Climate Change Implications: Urbanization can exacerbate the urban heat island effect, contributing to localized climate change. This can further stress ecosystems and species already grappling with changing environmental conditions.

Ecosystem

Ecosystem Biodiversity

Ecosystems and biodiversity are closely intertwined and mutually dependent. Ecosystems are composed of a variety of species interacting with each other and their physical environment. Biodiversity, which encompasses genetic diversity, species diversity, and ecosystem diversity, is the key driver of the complexity, stability, and resilience of ecosystems.

Ecosystem Structure and Function: Biodiversity determines the composition of species within an ecosystem, including producers, consumers, and decomposers. Each species contributes to ecosystem functions such as nutrient cycling, energy flow, and decomposition, which collectively maintain the stability and productivity of ecosystems.

Ecosystem Services: Biodiversity is essential for providing ecosystem services that directly benefit humans, including clean water, pollination of crops, regulation of climate, and provision of food and medicines. A diverse array of species contributes to the resilience of these services, making ecosystems more capable of withstanding environmental changes.

Food Webs and Trophic Interactions: Biodiversity influences the structure of food webs and trophic interactions within ecosystems. A complex food web with many species interactions can provide stability by preventing any single species from dominating or collapsing the ecosystem.

Resilience to Disturbances: Biodiversity enhances the resilience of ecosystems to various disturbances, including natural events like wildfires and human-induced pressures like pollution. Diverse ecosystems are often better able to recover from disturbances and resist invasion by non-native species.

Genetic Resources: Biodiversity is the source of genetic material for species, allowing them to adapt to changing environmental conditions. Genetic diversity within species is essential for breeding programs in agriculture, forestry, and conservation.

Habitat and Niche Diversity: Biodiversity contributes to the diversity of habitats and niches within an ecosystem, allowing different species to occupy specific roles. This niche diversity reduces competition among species and promotes coexistence.

Indicator of Ecosystem Health: Biodiversity serves as an indicator of ecosystem health and ecological integrity. A decline in biodiversity can signal disturbances or environmental degradation within an ecosystem.

Cultural and Aesthetic Values: Biodiversity is culturally and aesthetically valuable to humans. People derive inspiration, cultural significance, and recreational enjoyment from diverse landscapes and ecosystems.

Global Implications: Biodiversity loss can have global consequences, as it can lead to the disruption of biogeochemical cycles, changes in climate regulation, and the collapse of ecosystem services that support human societies.

Conservation Easements

& Biosphere Reserves

Ecosystem Biodiversity Efforts

Ecological Restoration: Restoration initiatives aim to revitalize entire ecosystems that have been degraded or damaged. This can include restoring wetlands, grasslands, or forests to their natural state.

Conservation Easements: Conservation easements are legal agreements between landowners and conservation organizations or governments. They restrict land use to protect ecosystems and the species within them while allowing landowners to retain ownership.

Biosphere Reserves: UNESCO's Man and the Biosphere (MAB) program designates biosphere reserves to promote the sustainable coexistence of people and nature. These reserves include core protected areas, buffer zones, and transition areas.

Sustainable Land Use Practices: Promoting sustainable agriculture, forestry, and fisheries practices helps maintain the health and diversity of ecosystems while meeting human needs.

International Agreements: International treaties and agreements, such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), promote the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity at a global scale.

Species

Species Biodiversity

Species biodiversity, often referred to as species diversity, is a fundamental aspect of biodiversity. It encompasses the variety and abundance of different species within a given ecosystem or across the planet. Species diversity is a key indicator of ecosystem health and plays a crucial role in maintaining ecological balance and ecosystem functioning.

Definition and Measurement: Species biodiversity is typically measured using metrics like species richness (the number of different species present) and species evenness (the relative abundance of each species). It can be evaluated at various scales, from local ecosystems to entire biomes or the global scale.

Importance for Ecosystems: High species diversity contributes to ecosystem stability and resilience by enhancing the ability of ecosystems to withstand disturbances. Each species plays a unique role in the ecosystem, often referred to as its ecological niche, which contributes to the overall functionality of the ecosystem.

Economic Value: Species diversity is economically valuable as it provides a wide range of ecosystem services, including pollination of crops, regulation of pests, and purification of air and water. Many industries, such as agriculture and pharmaceuticals, depend on genetic diversity within species for crop breeding and drug discovery.

Cultural and Aesthetic Value: Biodiversity has cultural significance for human societies, often being integral to cultural practices, traditions, and beliefs. Many people also derive aesthetic and recreational value from diverse landscapes and ecosystems.

Threats to Species Biodiversity: Human activities, including habitat destruction, overexploitation, pollution, and climate change, pose significant threats to species diversity.

Invasive species can also disrupt native ecosystems and lead to the decline of native species.

Species Extinction: The loss of species through extinction is a significant concern. Extinction can result from various factors, with human activities being a primary driver.

Conservation actions seek to prevent the extinction of threatened species and recover populations that are in decline.

Keystone Species: Some species have a disproportionately large impact on their ecosystems and are referred to as keystone species. Their presence or absence can dramatically affect the structure and function of entire ecosystems.

Species Discovery and Classification: Our understanding of species diversity is continually evolving as new species are discovered and taxonomically classified. Advances in DNA analysis and molecular biology have revolutionized the field of species identification and classification.

Legal Protections: Many countries have laws and regulations in place to protect endangered and threatened species, making it illegal to harm or exploit them. International agreements like CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) regulate the trade of endangered species.

Protected Areas &

Habitat Restoration

Species Biodiversity Conservation Efforts

Protected Areas: The establishment and management of national parks, wildlife reserves, and marine protected areas help safeguard a wide variety of species. These areas provide critical habitats for numerous species to thrive without disturbance.

Endangered Species Act (ESA): Legislation like the ESA in the United States provides legal protection for endangered and threatened species. It prohibits harming or trading these species and promotes recovery efforts.

Invasive Species Management: Efforts to control and manage invasive species help protect native species from competition and predation by non-native invaders. Methods include removal, biocontrol, and prevention of further introductions.

Habitat Restoration: Restoration projects focus on rehabilitating degraded ecosystems, enhancing habitats for native species, and reintroducing species into their historical ranges. Examples include wetland restoration and reforestation programs.

Genetic

Genetic Biodiversity

Genetic biodiversity, also known as genetic diversity or genetic variation, is a crucial component of overall biodiversity. It refers to the variety of genes and genetic characteristics present within and among populations of species. Genetic diversity plays a fundamental role in the adaptability, resilience, and long-term survival of species and ecosystems.

Genetic Variation Within Species: Genetic diversity manifests as differences in the genetic makeup of individuals within a species. This variation can include differences in traits like color, size, disease resistance, and behavior.

Importance for Species Survival: Higher genetic diversity within a population often means a better chance of survival in the face of environmental changes or the emergence of new threats. Inbreeding, which occurs when closely related individuals breed, can reduce genetic diversity and increase the risk of genetic disorders and reduced fitness.

Resilience to Environmental Changes: Populations with high genetic diversity are more likely to have individuals with genetic traits that enable them to survive and reproduce under changing environmental conditions.

Genetic diversity contributes to the resilience of species and ecosystems in the face of disturbances such as diseases, climate fluctuations, and habitat changes.

Conservation Implications: Genetic diversity is a critical consideration in conservation biology and the management of endangered species. Maintaining and restoring genetic diversity through strategies like genetic rescue, translocation, and breeding programs can be essential for the survival of threatened populations.

Cultural and Economic Value: Genetic diversity is valuable for agriculture and food security. Diverse gene pools in crop plants and livestock species help improve resistance to pests, diseases, and environmental stressors.

Human Impact on Genetic Diversity: Human activities, such as habitat destruction, overharvesting, and introduction of non-native species, can reduce genetic diversity in natural populations. Fragmentation of habitats can isolate populations, leading to genetic bottlenecks, where only a subset of genetic diversity survives.

Ex Situ Conservation

& Breeding

Genetic Biodiversity Efforts

Ex Situ Conservation: This involves maintaining populations of endangered species in controlled environments, such as zoos, botanical gardens, or seed banks. It helps preserve genetic diversity and provides a safety net against extinction.

Breeding Programs: Conservation breeding programs aim to maintain or increase genetic diversity within captive populations, ensuring the long-term viability of species. These programs often involve selective breeding to avoid inbreeding.

Seed Banks: Seed banks store seeds from a wide range of plant species, preserving genetic diversity for future restoration and research purposes. Examples include the Millennium Seed Bank in the UK and the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway.

Genetic Rescue: In situations where populations have become small and genetically compromised, genetic rescue efforts involve introducing individuals from genetically diverse populations to increase genetic variability.